Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

With the increase in renewable electrical generation, transportation has become the highest emitting sector of the US economy, accounting for about 29% of total greenhouse gas emissions. Light-duty vehicles, including cars and small trucks, account for about 57% of transportation emissions. Medium- and heavy-duty trucks contribute an additional 26%, while buses and motorcycles combined add approximately 1–2%. Altogether, ground vehicles are responsible for approximately 84–85% of total transportation emissions. Progress on this has been slow, with the USA lagging significantly behind other major jurisdictions in adoption of electric vehicles of all scales. This isn’t likely to change much.

To be clear, the Biden administration is trying. Their aspirational and sometimes well-aligned transportation blueprint calls for significant action in this sector, but any attempts to decarbonize US transportation face major headwinds for historical reasons. In the aftermath of World War II, a combination of fear of nuclear war, racism, and venal automobile manufacturers created the most extreme urban sprawl in the world. This led to a dispersal of industry, not a concentration in well-aligned clusters, as is the case in China.

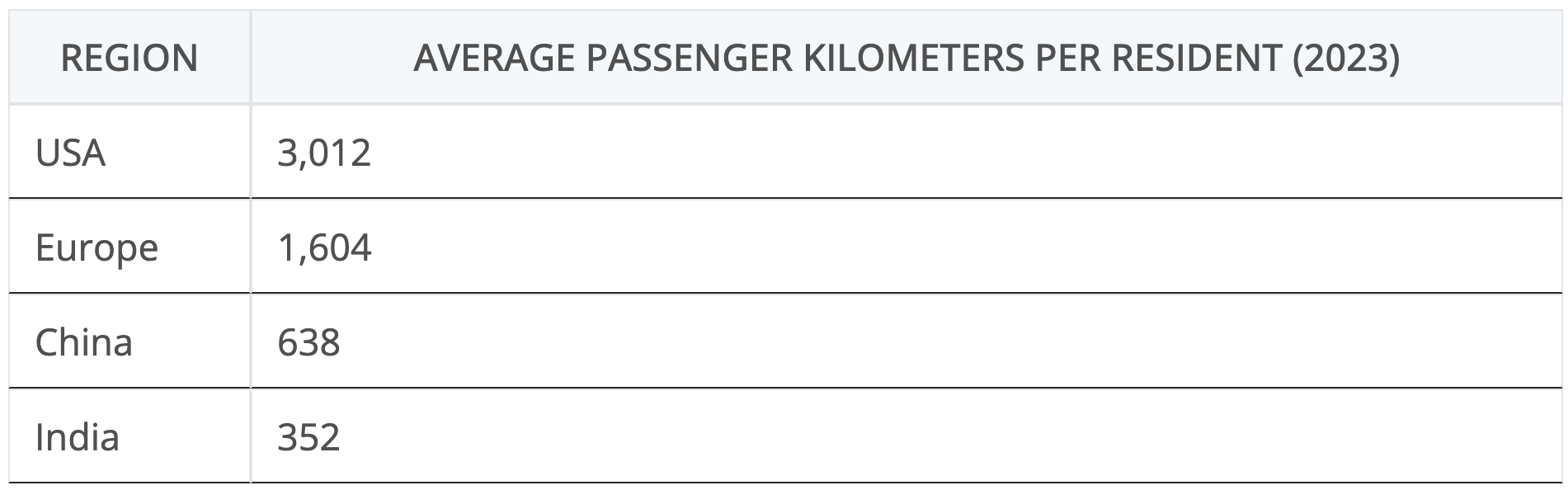

It led to the hollowing out of cities, with 92% of weekday trips in the country done by car, compared to 45% in Europe and 30% in Asia. Desires to shift human movement out of cars and into transit, walking, and biking will simply founder on the sheer distances traveled, the lack of density to support transit, and complete lack of walking and cycling infrastructure in the vast majority of the country.

This is combined with the rail problem. The rest of the world treats the rails themselves as national infrastructure, not private property. The USA, and by extension Canada and Mexico since those countries are typically forced to adopt whatever the USA does, for better or worse, simply because of economic integration, has had private rail since the days of the robber barons. US rail firms are strongly aligned with Jack Welch capitalism, which runs off quarterly stock analyst reports, not B-corp stakeholder models. US rail has twice the distance per ton as other geographies. The combination means that passenger trains are distinctly second class citizens on rail, shunted aside for any passing freight train, if they are allowed on shared tracks at all. Finally, a full third of US freight rail tonnage is coal and oil, mostly coal. That’s going away, so a third of their revenues are going away, and with it the revenues per track that pay for track maintenance. While the derailment rate has been managed down significantly since 1980, it’s likely to rise in coming years.

The above means that US rail won’t spend a dime on electrification or higher priced low carbon fuels, will lobby hard against those efforts, and has fiduciary duty to shareholders to hide behind. They will only electrify — the only real rail decarbonization strategy — if forced to, and there was zero recognition of the requirement to force this upon them in the blueprint.

Post World War II again, the massive military aviation industry pivoted to become a massive civil aviation industry, and people fly vastly more often and further per year than the rest of the world.

Another legacy of the Cold War is the massive system of highways, the longest in the world by far, 259,000 kilometers compared to China’s 177,700 (entirely built since 1987) and Europe’s 75,000. This supports the USA’s significant freight trucking industry as well as long commutes for workers.

Finally, there’s the Jones Act problem. While the USA has some of the best inland waterways and coastal conditions in the world for freight shipping, only 10% of domestic freight moves by water compared to China’s 20%. The USA has a third more coastline and the Great Lakes, but China has far more navigable waterways, in part because it has 40,000 kilometers of canals.

What does this have to do with the Jones Act? It is a significant inhibitor to domestic freight shipping in the USA. It requires that all commercial vessels transiting between two US ports be manufactured in the United States, be owned by US firms or citizens, be registered as US vessels and be crewed by American citizens. Combined with the USA’s lack of an industrial policy and deindustrialization since roughly 1980, this has led to a situation where the United States isn’t on the top 15 list of ship building countries globally while China took 59% of all new ship orders in 2023, with South Korea taking most of the rest. It has led to a situation where the US military fleet has three times as many vessels as the merchant marine fleet, when the numbers would need to be the inverse for the merchant marines to be a useful war time logistics force. And it has contributed to US domestic freight shipping languishing compared to road and rail.

Into this perfect storm of transportation decarbonization headwinds came the transportation blueprint. Its first section was all about shifting transportation modes to lower carbon ones, yet as the brief history above shows, the USA has no conditions for success for significant increases in transit, biking, walking, in shifting more freight to rail or water, or for building high-speed rail to get people out of airplanes. If the blueprint had acknowledged all of the above and made it clear how it was going to overcome these very high obstacles, it would be a worthwhile document, but it doesn’t.

Only electric road vehicles have a viable path to decarbonization at present, and that’s battery electric. Battery prices are plummeting, battery energy densities are increasing, electric cars can travel hundreds of miles on a charge and electric freight trucks are running 1,000+ mile days in the North American Council for Freight Efficiency’s Run on Less already. To be clear, none of this has anything to do with Biden’s or Trump’s policies.

Tesla and its investors drove North American validation of electric vehicles, and arguably much of the world’s as well, but they were starting with Mercedes Benz as a European partner and Panasonic as a Japanese partner. Their fiscal boat was floated by California credits, not federal credits. A federal loan a fraction of the funding that GM, Ford and Chrysler saw during the 2008 sub-prime mortgage debacle was repaid in full years ago. Biden has been more hostile to Tesla than supportive, mostly due to the requirement to placate his union base.

China has established complete leadership in this space, and once again that’s led to unprecedented tariffs, 100% on imported Chinese cars. This when US firms can’t build electric cars — or internal combustion cars — that 80% of Americans can afford to buy. US cars are aging rapidly, with the average car being required to run a third longer before being scrapped now than in 2000. To be clear, that’s due to long standing policies of tax cuts for the rich and low taxes on capital gains compared to labor income that have led to the worst income inequity in the G7, with the rich getting a lot richer and the rest of the country stagnating or even declining in real wages, and others of Biden’s policies are attempting to address at least some of that with some indicators of success.

The transportation blueprint also leans on hydrogen directly as a fuel and as a feedstock for synthesized fuels. Globally, that’s being proven to be exactly what analysts have been saying for a couple of decades, the most expensive possible way to decarbonize transportation, and hence one that won’t be adopted.

The IRA attempts to square this circle, including several provisions to subsidize low-carbon transportation fuels. One key provision is the Clean Fuel Production Credit, which offers a tax credit for producing low-carbon transportation fuels such as advanced biofuels, renewable diesel, and sustainable aviation fuel. The credit amount varies based on the lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions reduction of the fuel compared to traditional fossil fuels. Additionally, the act extends the existing tax credit for biodiesel and renewable diesel, providing a significant incentive to support the continued production and use of these biofuels.

The act also includes a tax credit for installing refueling infrastructure for alternative fuels like hydrogen, electricity, and natural gas. This credit covers up to 30% of the infrastructure cost, encouraging the expansion of refueling networks for low-carbon transportation options. A new tax credit specifically for sustainable aviation fuel is introduced, offering a per-gallon credit for fuel that achieves at least a 50% reduction in lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions compared to conventional jet fuel. Furthermore, the act expands and modifies tax credits for electric and fuel cell vehicles, including extending the existing electric vehicle credit and introducing new credits for used electric vehicles and commercial clean vehicles. Investment in research and development initiatives aimed at advancing low-carbon fuel technologies is also allocated, supporting next-generation biofuels, synthetic fuels, and hydrogen production.

Everything spent on hydrogen and fuel cells is money that is being thrown away. Everything spent on synthetic fuels is money that is being thrown away. Everything spent on natural gas is money that is being thrown away. The USA is attempting to subsidize decarbonization by spending a lot of money on the fuel, and that’s not sustainable.

In the absence of a sensible, robust, national carbon price on fuels, the administration has to rely on other levers. The EPA reinstated and strengthened vehicle emissions standards that were rolled back by the previous administration. This includes setting more stringent greenhouse gas emissions standards for passenger cars and light trucks for model years 2023–2026. To be clear, while a high carbon price is the single best policy for climate action, and any climate policy which excludes one is inadequate, most jurisdictions balance carbon pricing and regulation in different ways, as the impacts are felt somewhat unevenly and often politics intrudes. Balancing political feasibility of carbon pricing with regulations has been an acknowledged high wire act for a decade or more.

The Biden administration has also launched a comprehensive effort to expand the nation’s electric vehicle charging infrastructure, allocating $7.5 billion from the IRA to build a national network of 500,000 EV chargers by 2030. The funding will focus on deploying chargers in rural and underserved communities, along highways, and in urban centers, ensuring that EV drivers have convenient and reliable access to charging stations across the country.

Biden’s administration is trying, yet money is being spent in the wrong places, protectionism will radically slow electrification of road transportation, and the actual barriers to decarbonization are not being acknowledged and dealt with. The incentives for electric freight trucking uptake are a fraction of what they are in Canada and Europe, not enough to significantly move the needle in any reasonable time.

Trump’s campaign promises, unsurprisingly, are much worse. He would roll back the IRA provisions, electric vehicle subsidies, corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) standards, and most of the fuel subsidies — although, to be clear, not the ones that provide subsidies for blue hydrogen for the fossil fuel industry. His just-announced running mate seriously proposed giving the EV tax credit to internal combustion cars instead. Trump has floated the nonsensical idea of building ten “Freedom Cities” on federal lands, when the USA needs urban densification, not more cities in the middle of nowhere. He loves the economic nonsense of urban air mobility and wants to lean into innovation for transportation, when the solutions are already incredibly well understood.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy