Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

How much steel does a person need to have a “first world” standard of living? Most people in the developed world never think of this question. They just get up from their beds held together with steel screws and bolt, stand on their floors which are held up with steel reinforced concrete, make breakfast in their steel appliance-filled kitchens, eat with steel utensils, then head to work, often in cars made of steel, then turn on their steel-filled laptop or their steel machinery to start their workday.

Steel is ubiquitous. In the developed and developing world, not so much.

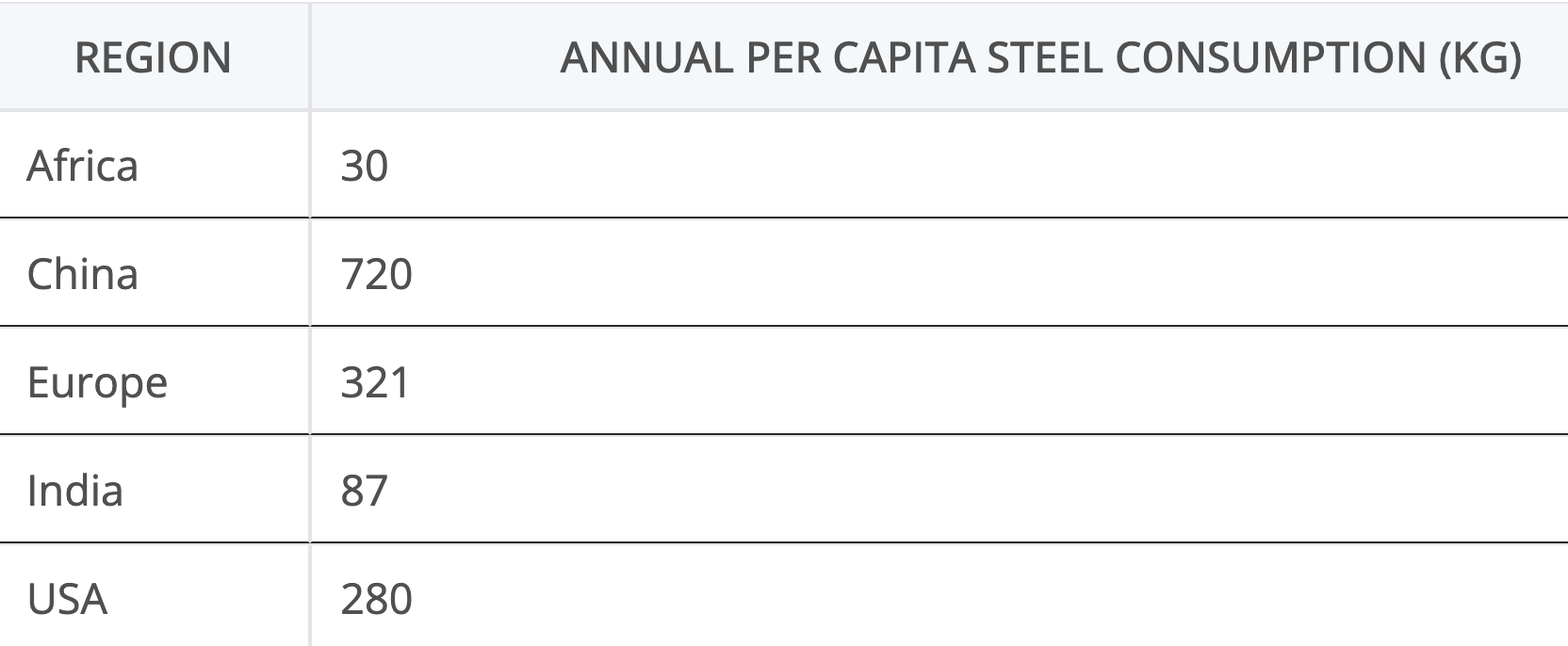

Sources for the annual per capita steel consumption figures include data from the OECD and the World Steel Association for Africa, information from the IEA’s Iron and Steel Technology Roadmap and the World Steel Association’s outlook for China, reports from Eurofer’s economic and steel market outlook, and mobilityforesights.com for Europe, insights from the IMARC Group’s market analysis and the IEA’s India Energy Outlook for India, and details provided by the American Iron and Steel Institute and mobilityforesights.com for the USA.

As the table shows, there’s a vast variance in steel consumption across the world. It’s safe to say that Europe and America constitute the “first world,” where every person has three to four times their body mass in steel consumed every year for their convenience, comfort, and possibly even profit.

The USA being below Europe was interesting. Sampling across the past 40 years indicates a significant decline in domestic consumption per capita from about 500 kilograms to current rates, while Europe has declined somewhat less. Some of this is due to deindustrialization, but the data also might be somewhat masked by the US rise of scrap steel to the current 71% through electric arc furnaces. Regardless, in the developed west, every person’s life is made more convenient, hassle-free, and economically viable in part because three to four times their body weight is put into the things around them, almost entirely without them noticing.

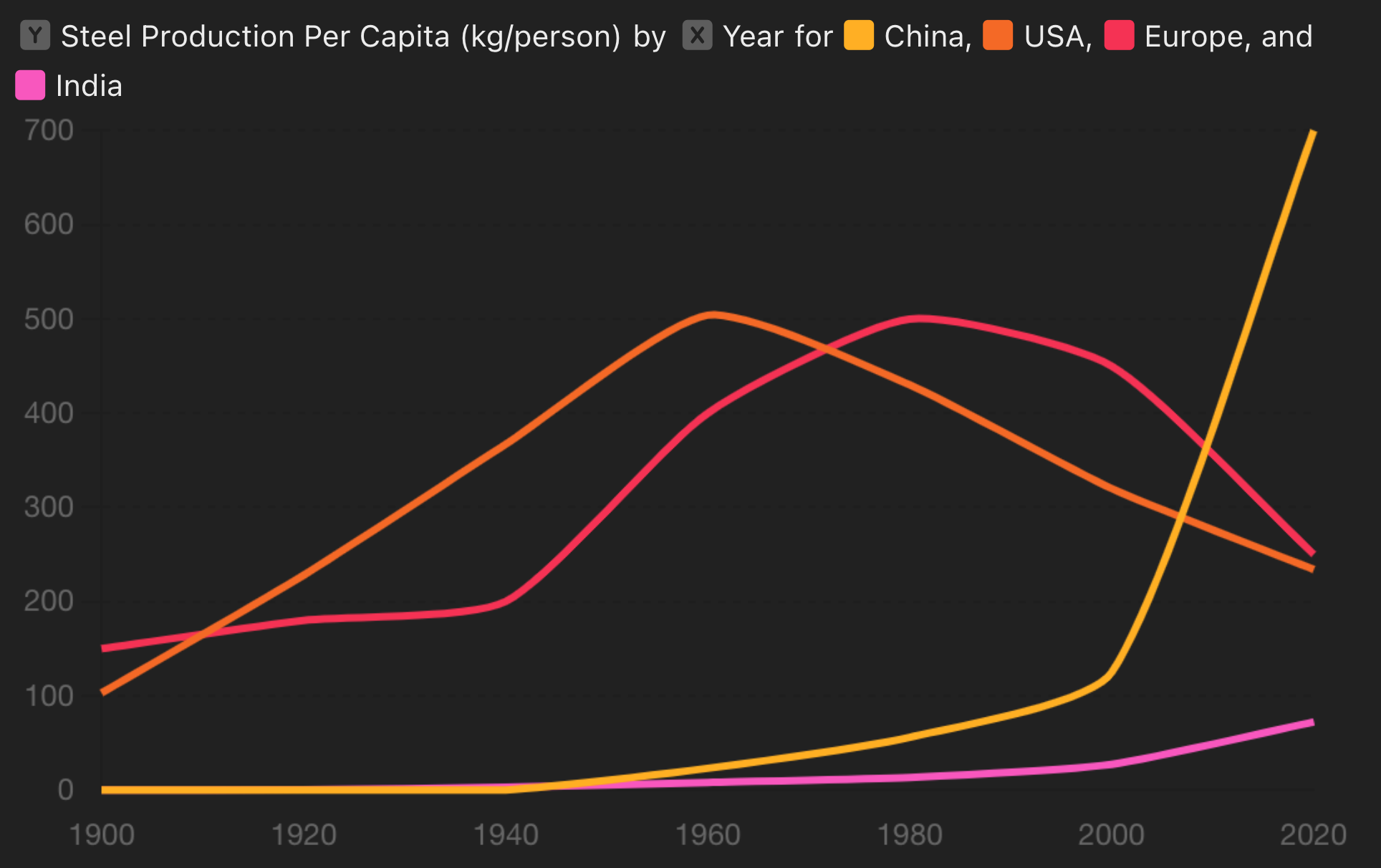

The US decline led me to ask if China’s per capita steel manufacturing is unusual for countries with significant heavy industry. I went back to 1900 for the UK and USA, the initiator of the Industrial Revolution and its most ardent adherent, then for China and India. (Note that these numbers were aggregated quickly with European numbers often estimated from national statistics, so take them as usefully indicative, not academically rigorous.) As can be seen, China’s current rate of steel manufacturing per capita is not nearly as far above the USA’s or Europe’s peak as current rates suggest, and it’s an incredibly recent turn of events. At present, the 1.1 billion people in Europe and the USA is lower than the 1.4 billion in China, but look at how long the two geographies were manufacturing enormous tonnages of steel using blast furnaces and coal.

I left Africa off of the graph as it’s a flat line along the bottom, but go back to the table and look at the number for the continent, only 30 kg of steel per capita recently. On that massive continent of 55 countries that holds 1.46 billion people, where the average body weight is only two-thirds that of Americans, they are still seeing only half a person of steel being consumed domestically annually. India is less dramatic, with 1.5 citizen’s mass worth of steel consumed domestically, almost 90 kilograms.

India is nowhere near Europe or America’s consumption per capita, but has been increasing the affluence of its population for decades to the point where there are only about 10% remaining in abject poverty. A clear goal of India’s governments of the past decades is to bring its population out of poverty, and it’s working. The consumption of steel is strongly correlated with increase in per capita affluence.

Also for context, the average American emits almost 5 tons of greenhouse gases just from their driving every year, dwarfing the roughly 1.4 tons of greenhouse gases per person from steel in China.

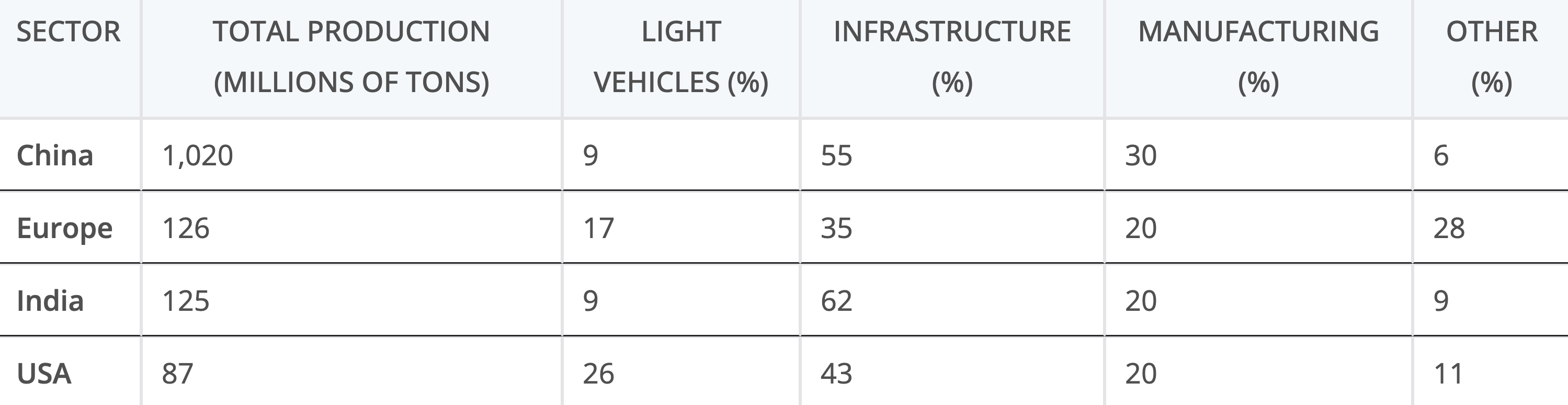

A more complete chart would include Japan, which until recently was also a steel manufacturing powerhouse, but this could rapidly get out of hand for the comparison in question, which is whether developing countries like India, the African nations, or Latin America have to see these major steel consumptions per capita that the first world nations have and China currently has. To answer that, let’s look at the patterns for where steel is used in different countries or geographies. Once again, this was rapidly assembled from multiple sources to provide an indicator, not a precise and wholly reliable comparison, but it’s sufficient for the purpose.

I spent a bit more time putting together this table of major demand sectors for steel in each of the geographies, along with the total amount of steel each geography was manufacturing. A couple of things pop out.

As recent statistics pointed out, North Americans are the ones not in step with the world, as 92% of all weekday trips are by car, compared to 45% for Europe and 30% for Asia. Yet these ratios don’t seem to reflect that. What’s going on?

First, the United States not only manufactures about 10 million light vehicles a year, it imports another 6 million or so, with almost 5% of its populace — statistically, not in reality — buying a new car each year. Europe, by contrast, exported 1.4 million more light vehicles than it imported, being the most trade-dominated geography, while China exported almost 16% of its light vehicles. Countering that somewhat, the USA’s light vehicles are anything but, about 1.9 metric tons on average, compared to Europe’s 1.4 tons, China’s 1.5 tons (due to so many more electric vehicles being built and sold), and India’s 1.2 tons. In the USA and Europe, of course, a far larger percentage of people are buying replacement cars or adding to their personal fleet than in other countries.

The combination means that the ratio of trips is the more telling statistic. The developing world isn’t going to end up with the same car and light truck dependency and hence domestic steel demand as the first world. Its cities are denser to begin with and are intelligently building massive transit networks instead of sprawling suburbs. The infrastructure isn’t being built for massive numbers of huge personal vehicles, unlike North America where a combination of nuclear war terror, racism, and corporate venality created massive sprawl and a resultant huge road network, three times more distance per capita than Europe, five times more than India, and six times more than China, at least according to the statistics I could draw together.

But let’s turn our attention to that big bulge of infrastructure and construction. China and India are pumping a vastly larger percentage of their steel into long term economic assets such as cities, railroads, subways, water systems, dams, transmission, and the like than Europe and North America. This is completely reasonable, as they were often lightly supplied with those things prior to 1980 or 1990. For example, I recently discovered that China didn’t have highways to speak of in 1987. Now it has 177,000 kilometers of them, second only to the United States with its quarter million miles of the things. Similarly, China didn’t have high-speed rail prior to 2007, yet now it has 45,000 kilometers or so, far more than the rest of the world combined.

Buildings are huge consumers of steel within reinforced concrete. So are bridges. So are dams. So are water systems. But as I’ve noted in my concrete month series, there are a large number of ways to cut steel down or out of the concrete equation entirely, and all of them are accessible to the developing world. Some of them are even cheaper, so will be used almost automatically.

Let’s start with the obvious thing. The developed world overuses the stuff in our buildings because we’re affluent and liability-averse. It’s easier and has been cheaper to supersize walls and foundations rather than worry about future lawsuits. Our engineering rules of thumb have become bloated, not lean and athletic. Carbon pricing and regulations on embodied carbon will force us to put our construction on a diet. We’re already seeing up to 20% higher costs per ton of reinforced concrete in Canada and Europe and that’s going to drive change.

But the developing world isn’t pricing carbon yet. Instead, it just doesn’t have nearly as much money to waste as Europe or the United States. Its developers are going to stay lean. Most of the substandard development has run its course and construction is completely safe, but it’s not overly safe.

But software is cheap. Between generative architecture that can design and redesign a building a thousand times to find the optimal use of materials and finite element analysis which can determine exactly how much reinforced concrete is required in different parts of a building to maintain structural integrity, buildings can use up to 20% less concrete for the same safety, and even more in sometimes bloated western developments. Safer buildings with less material means that India and China’s modern infrastructure build-out will cause fewer carbon emissions than the developed world’s.

But there are a couple of additional things which will likely play out immediately. The first is fiberglass mixed in with concrete, allowing broader slabs to be poured with lower labor and time, with no steel involved and at a lower overall embodied carbon. The second is carbon fibers, which can cut the weight of load-bearing structures by reducing or eliminating steel and requiring less concrete, substantially reducing overall embodied carbon. The software listed above already knows how to deal with both of these steel alternatives and can run through to cost comparisons. In many cases, it will be less expensive to use these approaches than traditional technologies.

Developing world architects and structural engineers are not remotely unsophisticated or technically incompetent. As they build their countries’ futures, they will be leveraging a suite of tools that were not available during the massive infrastructure deployment in the first world, where slide rules and pencils were often the available tools for determining the volume and composition of load-bearing structures. There are strong advantages to building in the age of ubiquitous computing and advanced materials science, and the developed world is reaping those benefits.

There is one other big factor associated with this. Remember the graph of China’s steel production and consumption shooting up even as the USA and Europe’s ramped down fairly quickly. A bunch of that was due to the west deindustrializing, especially the USA, but a bunch of it was due to both Europe and the USA having built most of the infrastructure that they required, while China had to catch up rapidly. China’s construction boom is coming to an end. It has most of the cities, railroads, highways, and water systems that it requires. It has to finish replacing coal plants with wind, water, solar, storage, and transmission, and it’s doing that incredibly rapidly, but all of the steel it’s consumed in building a modern economy over the past 45 and especially the last 25 years is just going to sit there bearing load. It’s moving into maintenance and replacement mode.

The rest of the world doesn’t have the conditions for success for that extraordinary infrastructure build-out. I’ve lived and worked in Brazil, and even spoke the language well enough to hold conversations and have business meetings, if haltingly. It doesn’t stand a chance of the development that China achieved. I’ve spent time in Indonesia, and it’s not going to become a major manufacturer any time soon, and has only 20% of the population of China in any event. Stepping through the BRICS block, Russia is collapsing economically, throwing people and increasingly old equipment into a meat grinder, burning through its monetary reserves, losing revenue due to sanctions and Ukraine’s very successful oil infrastructure strikes, and paying other countries through the nose for refined oil and weapons. South Africa was a shining light in the early 2000s, but far from it since.

The point is that the rest of the world will be building infrastructure a lot more slowly than China did. They don’t have the odd conflation of factors that enabled it. That means that while there is going to be growth of demand for steel outside of China, it’s likely to diminish inside the country, and as China produced 57.3% of the world’s total steel in 2023, global steel demand is likely going to decline in the coming decades. China already has 59% of global ship orders, so how many more shipyards does it need? It already has 90% or more of the highways and railroads it requires. There’s a lot more wind, solar, storage, transmission, and hydro to build, but the country will be able to start scrapping a lot of fossil fuel infrastructure in the coming years as well.

The developing world will build a lot more intelligently and with a lot more advanced materials than the first world did. They are unlikely to see booms like the post-WWII boom in Europe and America, or the post-1980 boom in China. Even as we decarbonize steel and cement, demand is likely to diminish, not increase.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.