Extreme weather events have been burning, flooding, and freezing the country for years. And now, as the U.S. cranks its air conditioners to get through historic high temperatures, the need for energy that slows, not hastens, climate change is more apparent than ever.

Yet, in 2022, almost 40% of electricity in the US was generated by power plants fueled by natural gas. (Note: “Natural gas” is an industry misnomer; UCS considers methane, fossil gas, and gas to be much more appropriate terms. I’ll be using the term “gas” from here on out.) These gas plants produce significant heat trapping emissions despite a plethora of data that we need to reduce our heat trapping emissions while also meeting increased power demands. In a maddening loop, those emissions are contributing to more extreme weather events, which are straining our power grid.

We need more electricity to transition our homes and cars off fossil fuels, but we can’t afford to let that electricity come from more gas power plants.

Gas plants are still too numerous

Let’s look at some numbers to get an idea of the state of gas in the U.S.

As of 2022, there were approximately 2,000 gas power plants with a combined capacity of 500 gigawatts on the grid. Gas power plants account for about 43% of utility-scale electricity capacity, slightly higher than the 40% of electricity generated from gas in 2022. Over the year, those plants emitted 661 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, more than 13% of the US’s energy-related carbon dioxide emissions.

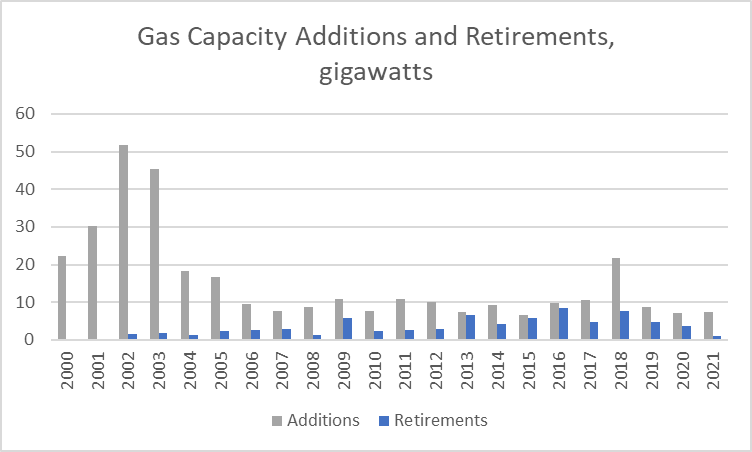

Between 2000 and 2022, gas capacity has grown more than four-fold, with a big uptick coming online in the early 2000s. This was due in part to advancements in hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) that allowed for easier gas extraction from shale gas deposits; it resulted in devastating impacts for communities near these sites. The rapid growth of gas plants was also driven by gas-friendly policies and generous financial investments in the industry, despite high costs to consumers.

More recently, the annual capacity from gas plants coming online has plateaued while retirements are slowly increasing. Aging plants and state clean energy goals are certainly helping that trend. But we’ve also reached the point where the economics of renewables are just much better. On a levelized cost basis (a fancy term for the average cost of electricity over the generator’s lifetime), utility-scale renewables are cheaper and those costs keep going down.

Source: Energy Information Agency

Despite the economics increasingly favoring renewables, an additional 21.8 gigawatts of capacity from gas plants are planned to go online from 2023 to 2026. Many of these gas plants are concentrated around the Midwest and Texas, which have pipeline access to notable shale deposits.

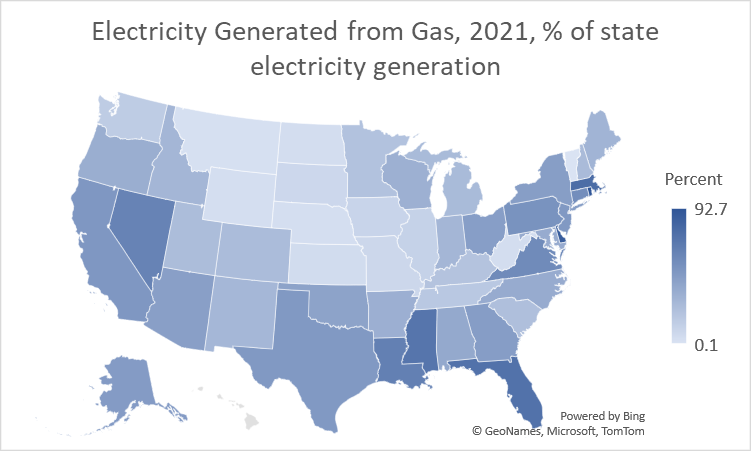

Regions remain uneven in their transition away from gas

While markets and climate science suggest we should be moving away from gas, the transition isn’t happening uniformly across the country. States remain widely varied on their reliance on gas for electricity. This is a combination of state policies, existing gas infrastructure, geography, weather, and demographics.

Unsurprisingly, states and regions located near shale gas deposits and pipeline infrastructure remain reliant on gas—this is the case for Texas and the Appalachia region. Also unsurprisingly, states with large populations are using the most gas to keep their grid running.

Source: Energy Information Agency

It might be surprising to see a state like California pumping out so much gas-generated electricity since it’s generally considered a leader in the clean energy transition. But with a population of 40 million and increasingly hot summers that are maxing out the grid, state officials continue to prop up gas plants as a misguided solution to keep the lights on.

But increasingly we’re seeing gas plants fall short on their promise to keep those lights on. Many regions (e.g., California, mid-Atlantic, and Texas) have already experienced extreme weather events where gas plants have failed to perform. With more extreme weather events being driven by continued fossil fuel use likely in the future, gas isn’t the key to grid reliability and states should more proactively plan for alternatives.

Gas disproportionately harms vulnerable communities

At a more localized level, the distribution of our gas infrastructure reveals a glaring equity issue. That’s because a disproportionate number of plants and extraction sites are concentrated in communities of color and low-income communities, highlighting a legacy of racism and socioeconomic discrimination in our electricity system.

Why is this inequitable and disproportionate siting a problem? Because unlike moving sources of air pollution like cars, gas plants are completely stationary. It’s an obvious, but important characteristic because it means the impacts of gas plants accumulate to the local community.

Gas plants release heat trapping emissions that go into the atmosphere and contribute to the climate crisis, and this affects us all. But gas plants also release emissions of nitrogen oxides, more commonly referred to as NOx emissions, that contribute to smog and other pollutants. NOx emissions stick around locally, with major health consequences to nearby residents. The cumulative impacts of NOx emissions on local communities can be devastating, including respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, and premature death.

We know that gas plants have been sited inequitably, and the associated harms have had cumulative impacts on neighboring communities. As we look to phase out gas, we should prioritize plant retirements in communities of color and low-income communities.

We’re not turning down the gas yet

The climate crisis is getting worse, and it’s being partially powered by the country’s over-reliance on gas. Unfortunately, we’re not easing off the (methane) gas pedal fast enough, despite modeling by UCS and others showing that we need little to no new gas plants for grid reliability.

If we’re going to allow new plants to come online, we need to address the two major problems that will come with them: pollution and grid (un)reliability.

The Environmental Protection Agency is currently updating multiple pollution standards for new and existing fossil fuel-fired power plants. Some of these standards—including limits to carbon pollution and smog-forming pollution—could help mitigate the immense harm that gas plants impose on the environment and surrounding communities. Strong standards that reflect these high costs will also emphasize how much more economical clean alternatives are for the grid, setting up a faster transition away from gas.

As for reliability, we’re increasingly seeing that gas is not as reliable as advertised. Grid planners are calling on gas resources when times get tough, and those gas plants aren’t always showing up. Those planners need to update how gas contributes to grid reliability because the current accounting methods aren’t adding up.

But ultimately, it’s time to acknowledge that continued long-term investment in gas power plants isn’t the path forward. Renewables, storage, transmission, energy efficiency, and demand response are all fantastic options to piece together a clean, affordable, reliable, and equitable grid.

We need a just transition

It won’t be an easy transition to turn down the gas. A history of gas-friendly policies and regulations has pushed the United States to over-invest in gas infrastructure and systems. Industry powers with financial and political clout aren’t willing to give up their profits for a cleaner and healthier planet despite having known for decades the harm that fossil fuels inflict. I hope these companies will be held accountable.

But as we transition away from gas, we also need to be accountable to the communities of color and low-income communities that have been and continue to be disproportionately harmed by fossil fuel interests, as well as the people and communities who rely on the gas industry for their livelihoods.

Our over-reliance on gas has contributed to grid reliability crises while disproportionately harming vulnerable communities. By focusing on a just transition to clean electricity, we can accelerate our phase out of gas and build a better, more equitable grid for all.

By Vivian Yang, Western States Energy Analyst, courtesy of Union of Concerned Scientists, The Equation.

I don’t like paywalls. You don’t like paywalls. Who likes paywalls? Here at CleanTechnica, we implemented a limited paywall for a while, but it always felt wrong — and it was always tough to decide what we should put behind there. In theory, your most exclusive and best content goes behind a paywall. But then fewer people read it! We just don’t like paywalls, and so we’ve decided to ditch ours. Unfortunately, the media business is still a tough, cut-throat business with tiny margins. It’s a never-ending Olympic challenge to stay above water or even perhaps — gasp — grow. So …