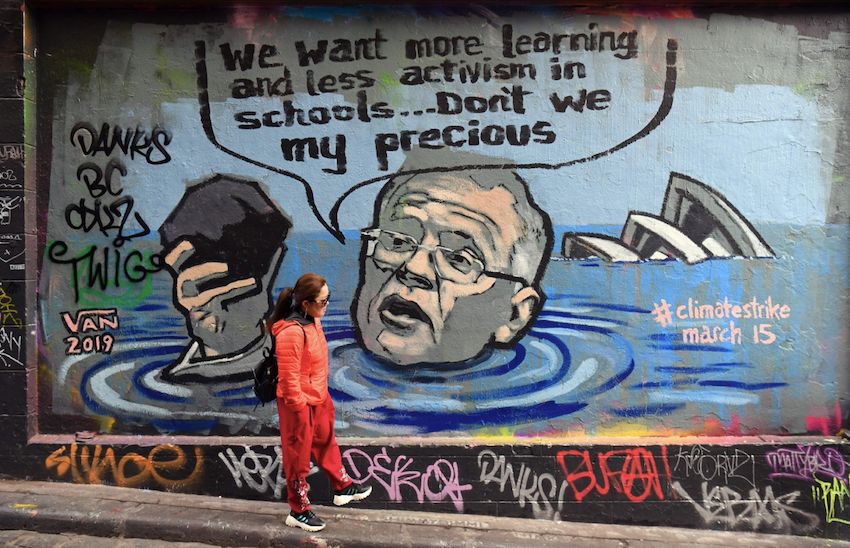

Holding up a lump of coal while addressing the Australian Parliament in 2017, then Treasurer Scott Morrison proclaimed, “This is coal. Don’t be afraid of it!”

Morrison proudly held his piece of coal aloft, he aimed to signal two things. First, that coal has been key to the country’s growth and fortunes. And second, it is unlikely to go away anytime soon.

Six years hence, when it comes to addressing matters around coal, Australia remains indecisive.

In July this year, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, who came to power in May 2022 approved an extension to the life of the Ensham thermal coal mine. This was the third approval for coal extraction to be approved by the Australian government between May and July.

Albanese’s government came to power with promises of stricter emissions targets and increased renewables investment. While the former Morrison government refused to budge from its 2030 target of cutting 26-28% emissions compared to 2005 levels, Albanese doubled the figure, and promised to reduce CO₂ emissions by 43% of 2005 levels by 2030.

Did the actions match the promises? Perhaps not, environmentalists say. The Ensham mine, in Queensland, will eventually add an additional 100 million tonnes of CO₂ to the atmosphere. The 4.5 million tonnes of coal produced each year by the mine will be used in power stations.

Australia is world’s second largest exporter of coal and added A$112.8 billion to the country’s export revenue in 2022. According to the Minerals Council of Australia, the coal industry employed around 46,000 people last year, and is projected to employ around 67,500 people by 2025. With approvals for new mines and projections of increasing employment, can net-zero targets and coal co-exist in Australia?

Rebranding Australia as a clean energy hub

When asked whether Australia’s target to meet net-zero by 2050 meant the end of coal was in sight, Australia’s former emissions reduction minister Angus Taylor said that the government’s focus was on developing technology and not “on wiping out industries”.

Denouncing the government’s strategy as a “fantasy plan”, climate and energy minister Chris Bowen said in July that he had asked the Climate Change Authority to change Australia’s net zero 2050 plan, replacing it with a plan detailing actions for decarbonising the electricity, building, transport, resources and land sectors.

Instead, Australia’s mining sector hit a record high of A$455bn in national export revenue in July, of which A$128bn came from coal exports.

The record value of coal exports from Australia could be partly attributed to the reopening of the Chinese economy in March this year. As China’s domestic demand for power generation and steel manufacture increased, the country’s coal imports increased by 151% from March 2022 levels, reaching a three-year high.

Business intelligence publication China Briefing showed a surge in coal imports from Australia in 2023, the majority of which is thermal coal. Imports rose by 122% in March, reaching $238m in value.

Despite setting up a Net Zero Authority and accelerating climate action plans, Senator Matt Canavan mirrored Scott Morrison in May this year, parading a lump of coal around the Australian Parliament.

“It’s budget day today, and I’ve got the budget surplus in my hand,’ he proclaimed while holding a small block of coal. “This budget surplus is all on the back of our mining industry and coal, and the record coal prices we’ve got.”

The Albanese’s government may be using the rhetoric of renewable energy to rebrand Australia as a clean energy hub, however its toxic relationship with coal continues unhinged.

Where does Australia stand on the coal question?

It is true that the mining industry has driven Australia’s economy for nearly three decades. But as a result Australia has the highest coal-based greenhouse gas emissions in the world, on a per capita basis.

Unlike other economically strong countries, Australia generates 91% of its electricity from fossil fuels, 75% of which comes from coal as of June 2023. Its power generation system is also the second most coal-dependent in the OECD, behind Poland.

Lobbying and exports of commodities like lithium, copper and nickel, used in energy transition are projected to increase between 20-30% for the next three years, yet, these will remain meagre earners against Australia’s export of iron ore and fossil fuels.

What is holding Australia back from taking drastic decarbonisation action?

At the heart of the issue is the country’s polarised politics around resources. Until 2021, Australia was not ready to take action on phasing out fossil fuels and refused to join the 40 countries that pledged an end to use of coal power ahead of the COP26 summit.

The situation worsened in the past three years due to the country’s gas-led economic recovery after the Covid-19 pandemic. When the Albanese government took power in 2022, it did little to change the direction on developing fossil fuels for export.

Despite its positioning on climate change, it continues to support domestic subsidies and favourable tax treatments for fossil fuel extraction. The country has further provided a A$50m subsidy to accelerate the development of priority gas infrastructure.

Right after coming taking office, the current government launched offshore petroleum exploration permits that opened up nearly 47,000km² of Australian waters to oil and gas exploration, as well as its coal mine approvals. The new projects contrast with Australia’s its nationally determined contribution (NDC) to emissions reduction, compromising its ability to reach its 43% emission reduction target.

Is Australia close to realising net-zero?

In July, Australia-based mining giant Whitehaven Coal revealed that Australia’s biggest banks had refused financing for a billion-dollar debt facility for the company. Does this send out a message that banks are increasingly wary of financing coal projects, and that an end to the fuel may be in sight?

Several of Australia’s big miners have announced their decarbonisation targets. Rio Tinto has set a target of reducing its scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas emissions by 50% by 2030, with a 15% reduction by 2025. So far, the miner has managed to reduce emissions by 7% by installing large-scale renewable power alongside its operations. Fortescue joined the bandwagon in 2022 and announced its plans to achieve net zero scope 3 emissions by 2040.

The question remains if these shifts are enough.

In November 2021, the Australia Institute estimated that 72 new coal projects and 44 new oil and gas projects were under development. If these were all to operate successfully in the coming years, it would add 1.7 billion tonnes of CO₂ emissions annually, equivalent to 200 coal power stations. While the country is shifting to renewable energy, its current share of renewables in electricity generation is a mere 7%.

Independent researcher Climate Action Tracker (CAT) has granted Australia an overall “Insufficient” tag based on its targets, policies and climate finance. It lists Australia’s monetary contribution to climate change as “critically insufficient”, saying in a report: “The Albanese government reiterated Australia’s commitment to net zero target by 2050 when it submitted its new NDC. Modelling commissioned by the Australian Labor Party shows high levels of emissions – of at least 60 MtCO2e – remaining in 2050, from facilities covered by the safeguard mechanism – largely in the industry sector.”

With an ageing coal power plant fleet, lack of rapid investment in renewables by the previous government, and a continuing legacy of approving fossil fuels by the current government, Australia’s promise of emissions reduction hangs by a thread.