Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Lloyd Alter is a man of many talents. He is an architect, real estate developer, tiny house advocate, and author who has written more than 15,000 articles for Treehugger since 2005. Many CleanTechnica readers may be familiar with his work or his books, one of which is entitled Living The 1.5 Degree Lifestyle. He also teaches sustainable design at Toronto Metropolitan University, and in his spare time, writes a blog on Substack called Carbon Upfront! In a piece this week, he focuses on sufficiency — a concept that used to be a normal part of life before the Super Size Me movement took hold and convinced us we needed 5,000-square-foot homes, gigantic cars and trucks, and yachts as big as the Queen Mary.

What has gotten stuck in his craw lately is Ontario’s mania for building more and more roads. He writes, “Where I live in Ontario, Canada, the government is ramming highways through the forests and farmland. It is spending billions to put streetcars in underground tunnels so that car drivers have the roads to themselves. Everything is bigger and faster. They never slow down and ask, what is enough? Can we afford the carbon emissions, the debt, and the environmental destruction that all of this building causes? What is sufficient?”

Sufficiency Is A State Of Mind

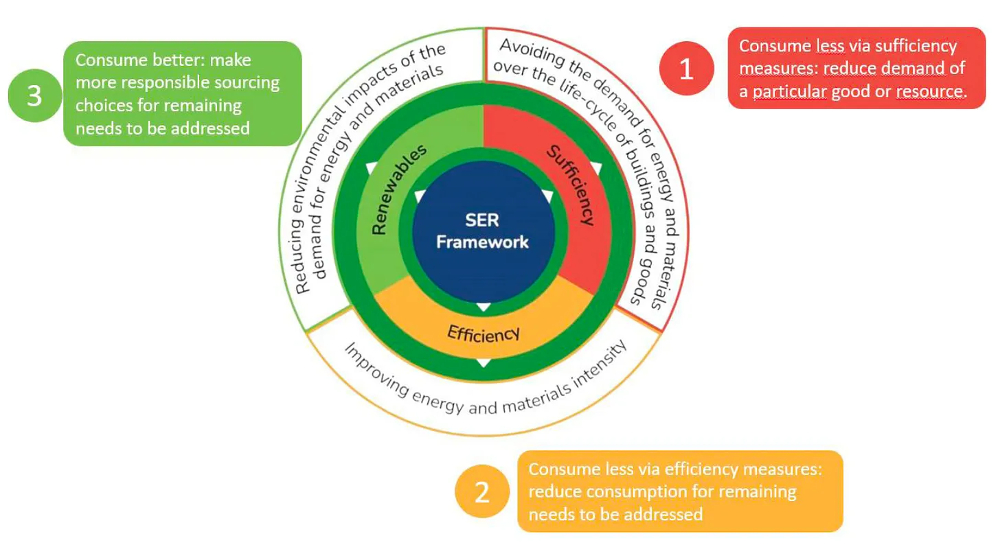

What is the definition of sufficiency? Alter quotes Yamina Saheb, who says, “Sufficiency involves a set of measures aimed at reducing the demand for resources such as energy, materials, land, and water, while ensuring human well being within the Earth’s ecological limits.” Readers may recall an author I hold in the highest regard wrote a story recently that argued the key to meeting the challenge of an overheating planet is to reduce demand. Mandates and taxes won’t curb greed of fossil fuel companies. They can pump all the oil and methane they can find, but if no one buys it, they will go broke and wither away.

There is now a Sufficiency Action Hub that is part of UN Environment Program’s Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction. It “aims to demonstrate the necessity, feasibility, and social desirability of sufficiency measures in the building sector, fostering a shared understanding across decision making levels. The Action Hub highlights the urgent need for sufficiency measures, advocating for a systemic approach that integrates demand-side policies to reduce resource consumption, mitigate emissions, and ensure social equity. Through international collaboration and the adoption of the “Sufficiency First” principle, the initiative aims to reshape the future of the building sector within planetary boundaries.”

On its web page, the Sufficiency Action Hub says, “Its goal is to build a diverse community of stakeholders worldwide, from various sectors of the building value chain, to adapt sufficiency solutions to different contexts, recognizing disparities between the Global North and South. Launched by the French Institute for Building Performance and supported by key institutions like ADEME, the initiative seeks to address the environmental challenges posed by the building sector, which is responsible for 21% of global greenhouse gas emissions.”

Sufficiency & The Built Environment

The Sufficiency Action Hub has released a report entitled “Sufficiency and the Built Environment: Reducing Demand for Land, Floor Area, Materials and Energy.” The lead author is Marine Girard, who until recently was the head of sufficiency programs for the French Institute for Buildings Performance. On LinkedIn, Marine writes,

“Despite efforts to decarbonize, the relentless demand for new floor area has offset gains in reducing the sector’s GHG emissions. This increased demand drives resources use, compounding emissions and contributing to planetary boundaries overshoot at large. To resolve the ecological overshoot and enable underprivileged societies to get access to sufficient infrastructure and shelters, we must shift priorities. This doesn’t mean stopping all current efforts but rather prioritize sufficiency – a set of policies and daily practices that avoid demand for material, energy, water and all natural resources while delivering well-being for all, within planetary boundaries.”

Alter points out that increased efficiency does not always lead to less consumption. If efficiency means more widgets get produced, then the price of widgets will fall and more people will buy them. Marine addresses that issue this way:

“In the long run, technical improvements do not lead to decreasing energy consumption and related emissions but rather allow for the expansion of the economy and related environmental externalities. Therefore, the major loophole of the efficiency strategy is to keep focusing on energy and technical-only oriented approaches without setting clear resource boundaries attributed to each sector and related products and services. This underlines the critical difference between consumption and demand and emphasizes the need for demand-reduction policies. It requires a fundamental shift in mindset, moving away from the pursuit of endless growth towards a more balanced and sustainable approach that prioritizes the well-being of both people and the planet.

“Sufficiency is first about policy making. A very small portion of individuals can change their behavior to adopt sufficiency practices in all aspects of life. The scale and degree of changes is too high to let people bear the responsibility of adopting wide changes at individual level. In fact, people are locked into the solutions imposed by the social infrastructure. Addressing sufficiency at the systems level moves away from the idea that sufficiency would be the responsibility of consumers, and to clearly identify the need to build — in terms of regulation, infrastructure, or corporate action — a range of system-level sufficiency measures.”

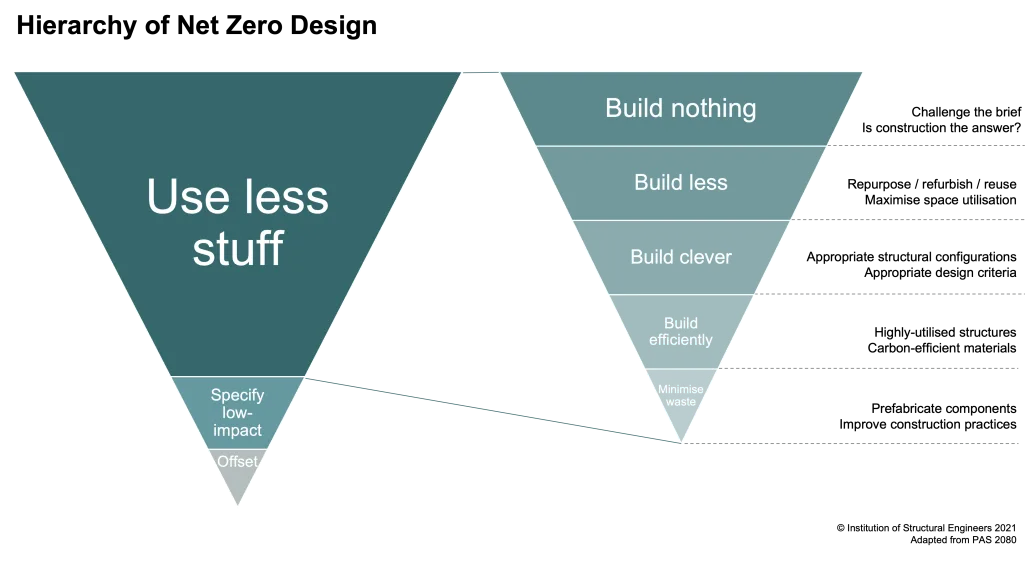

Many policies encourage sufficiency, Alter says. Zoning changes can promote Goldilocks density housing supported by bike lanes and transit. Economic incentives can promote renovation and re-use instead of new construction. Much can be done by designing things better. “Paying attention to space and quality of living should not only be defined by an absolute number of square meters. The surrounding amenities, quality of outdoor public spaces and available transportation and other services should also define the comfort and attractiveness of a space,” he says, before adding, “New buildings should be designed for compactness and flexibility, using low tech solutions to maximize comfort with minimum water and energy use.”

Leading up to COP29, where nothing of substance will be accomplished again this year, Lisa Richmond of Architecture 2030 has written that, “Consumption matters. Sufficiency — avoiding the demand for energy, materials, land, water, and other natural resources while delivering well-being for all within planetary boundaries — is a critical missing tool in our decarbonization toolkit. We cannot achieve our carbon reduction goals without building less.”

The Takeaway

When my sister and I would get rowdy in the back seat of my old Irish grandmother’s Plymouth on a road trip, she would look in the rear view mirror and say calmly, “That will be sufficient.” It was her way of telling us that if we didn’t change our behavior, unpleasant consequences would follow — and soon! Substitute Mother Nature for my grandmother and it’s easy to imagine her delivering much the same message to those of us who recognize no limits to our acquisitive natures.

Many of you had parents or grandparents who lived through the Depression. They had a knack for reusing, repurposing, and recycling things. Their motto was “make do” rather than consume and discard. There were no landfills in those days. Everything had a second or third use. It is popular to snicker up our sleeves at such quaint habits, but people like that had a lighter footprint on the Earth. We might be wise to put some of that wisdom to work today.

Where I grew up in Rhode Island, there was an organization called Save The Bay that was instrumental in promoting policies that limited pollution in Narragansett Bay. Some local road builders had bumper stickers printed that said Pave The Bay. The difference was only one letter but it illustrated how subtle changes in attitudes can lead to vastly different outcomes. Perhaps it is time we adjusted our own thinking about how and what we consume, and whether sufficiency might not be a pretty good blueprint for our lives.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy