Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Recently I published a projection of aviation decarbonization with a mix of battery electric and biofuels, including hybrid models, dominating through 2100 in Aerotime, an aviation industry specific journal that requested it. That triggered a lot of discussion, with some of the usual suspects chiming in on subjects they weren’t familiar with, such as increasing battery energy density with new chemistries, but also reasonable questions.

One of those questions was why bother to electrify short haul aviation at all instead of increasing rail usage? It’s a question worth exploring a bit more.

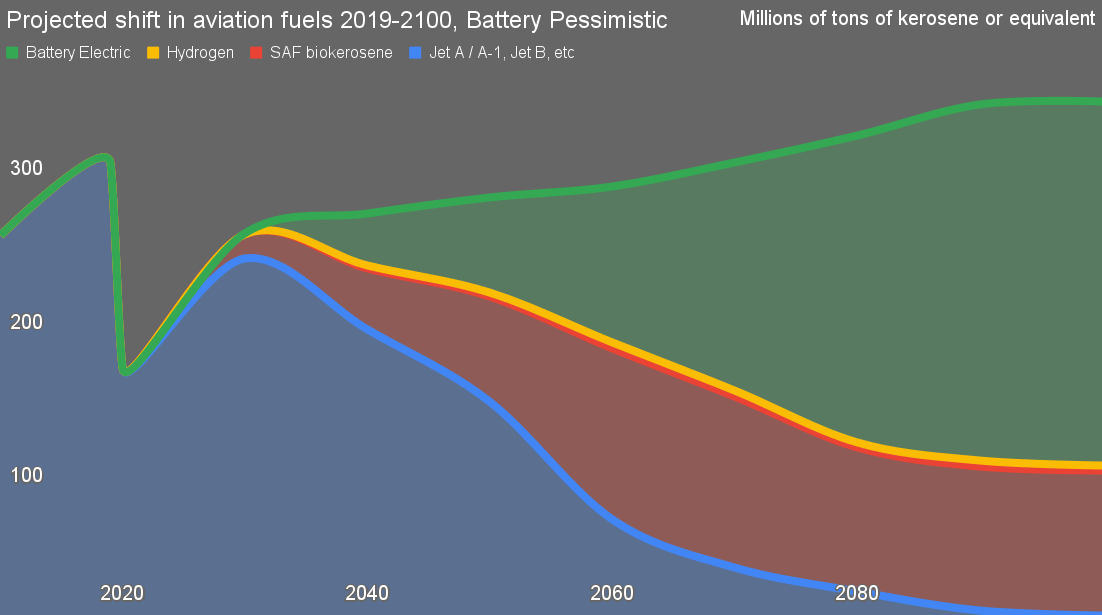

This is my iterated projection of aviation demand and energy supplies through 2100, first published in CleanTechnica three years ago. It was one of my earlier projections through 2100, so I hadn’t started my practice of casting back historically to 1990, as I’ve done with other domains like maritime shipping, steel and cement subsequently. That’s on my to-do list.

This is the most recent battery pessimistic projection, limiting it to potential energy densities of chemistries like silicon that are in the pipeline today. As a result, there’s a persisting requirement for burnable kerosene-equivalents through 2100, although still far lower than less realistic — in my opinion — projections, such as those that Boeing and IATA make.

A backward perspective would make much clearer how discontinuous my forward projection was with the past few decades of rampant growth of aviation. It would also make the arguments I make for flatter growth more obviously required to lay audiences who are less in touch with historical and current aviation patterns. To reiterate briefly, there are multiple pressures upward and downward on aviation demand.

Upward pressures include population growth, although that’s easing off and will stop between 2050 and 2070, and increasing affluence. Downward pressures include increased cost of flying, significant build out of alternatives such as high-speed rail, and the radical increase in high-bandwidth electronic communications as well as the cultural change toward their use forced by COVID.

The relevant downward pressure to the point of the question raised regarding rail is the growth of alternative means of moving around. This is especially prevalent in China, where the 45,000 kilometers of high-speed rail has had very obvious impacts on the passenger kilometers that people travel. In other words, the concern was factored in. However, in combination with another question it led me to ask what the ratio of rail to aviation trips was in multiple geographies.

I assembled a data set from 2000 through 2023 of passenger kilometers for Europe, the United States, India and China for both rail and aviation. Eight lines on a chart is far too busy, and so I aggregated it to the West and Asia. As China and India have 28% of the population of the world as well as being huge economies, and Europe and the United States a large percentage of western wealth and citizens, I felt this was an adequate comparison.

As a note about the data, it was assembled relatively quickly from multiple public sources and as such is imperfect. European data is most suspect as there are so many ways to count Europe, and they’ve changed with changes to the EU being a primary example. I sampled only 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2019, 2021 and 2023 to provide a trajectory over the past 25 years and to capture the dip during COVID, but there is significant variation from year to year for a variety of reasons. The data should be considered adequate for this analysis, but not definitive.

A couple of major differences between West and Asia aren’t immediately obviously from this simplified perspective without looking at it a little. The biggest one is that rail and aviation passenger kilometer dominance is inverted in the geographies. The burning orange, climate heating line at the top of the chart is of western aviation passenger kilometers. The big dip during COVID is indicative of how unnecessary much of flying really is. That it hadn’t returned to the same levels as pre-COVID by 2023 is indicative that some of the change is permanent.

By contrast, the big green line of climate virtue is Asian passenger kilometers by rail, which in both China and India are heavily electrified, so significantly lower CO2e per trip than the more diesel-prevalent rail in the West.

The yellow line of shame at the bottom of the chart is the passenger kilometers by rail in the west. The comparatively small dip indicates again that the journeys were more essential as well, less flying to Ibiza and more traveling for critical work or family emergencies.

The white line of Asian aviation passenger kilometers is interesting because it saw significantly lower annual growth than rail transportation, which is climate virtuous and once again inverted from the west’s flat passenger kilometers by rail.

However, this is a raw measure that isn’t adjusted for population. What if we divided the annual numbers by populations in those years?

Oops. Westerners fly vastly more kilometers per year than anybody else travels by any mode of transportation. The increase in casual, non-essential flying in the west is strongly indicated as the increase in kilometers per year was greater when adjusted for population, and the massive dip in flight kilometers for the average person, from about 3,100 per year to about 1,700 per year. Westerners fly like Asians go out for dinner it seems. Profligate, unnecessary flying is a climate problem and not one that’s nearly as common in even the most affluent and largest of developing nations.

The virtuous, climate-friendly green line of Asian rail still has a strong upward trend, indicating that Chinese and Indian citizens are traveling more, but dominantly doing it by rail.

The yellow line of rail avoidance shame in the West makes clear that rail ridership has been declining as a percentage of population since 1990, exactly the opposite of what climate action would suggest is appropriate.

The white line of Asian aviation is much flatter and closer to the horizontal axis from this perspective as well.

It’s worth pulling out a specific country from this and assessing rail vs aviation kilometers, China.

While Chinese aviation passenger kilometers did rise substantially, they were still outstripped by the rise of rail. Further, they dropped much more during COVID than did rail, once again indicative of the non-essential nature of substantial portions of aviation.

One thing to note about this is that enormous numbers of China’s passenger kilometers were on Chinese designed and manufactured aircraft. With the ongoing collapse of Boeing due to decades of ruinous mismanagement by Jack Welch’s acolytes, the same problem that caused the collapse and recent dissolution of GE itself, China’s COMAC will be Airbus’ primary competitor in coming decades, with Brazil’s Embraer addressing aspects of the market and new entrants with electrified solutions eating the bottom out of the regional market.

If China hadn’t built 45,000 kilometers of high-speed electrified rail making domestic rail travel fast and easy between their far-flung cities in a country the same geographical size as the United States, their rail transportation line would have been much more similar to the west and their aviation passenger kilometers would have been vastly higher. With the slowing of China’s economy and slower growth of other developing economies, aviation growth is likely to slow as well. A year or two more data will start to show a more realistic picture.

Another useful breakout is to look at the breakout of travel patterns specifically in the west.

Oops. Western travel statistics are heavily skewed by American travel patterns. The top line in climate heating orange is the average American’s flight kilometers per year. And do you see the thin yellow line across the bottom of the graph? That yellow line of shame is the annual average kilometers of rail travel for an American.

The two lines in the middle that are relatively close together are European aviation kilometers and below it the rail line. The gap between them isn’t huge, but of note, added together they aren’t as much as American flying. Americans fly an awful lot more than any other country or region in the world of any reasonably comparable size.

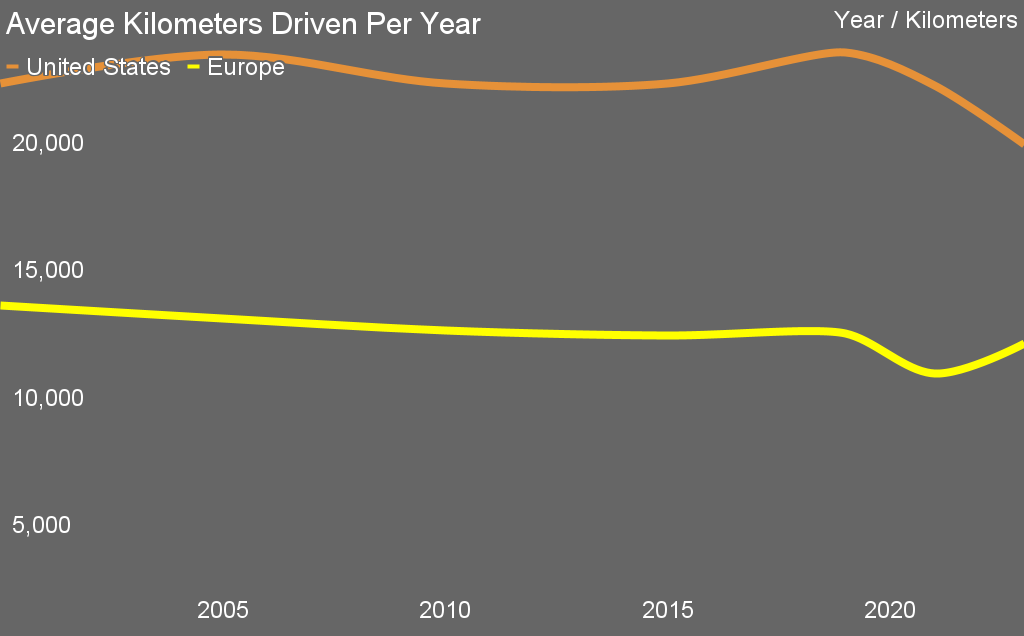

Of course, then there’s driving.

I would have included India and China in this comparison, but until recently in both countries so few kilometers were driven in personal passenger vehicles that neither country bothered to track total or average kilometers per year. They just aren’t driving countries. In China, at least, as they become a more passenger vehicle oriented country, having made it up to one passenger vehicle for every 5.5 people, they are now buying cars with plugs over 50% of the time, so it’s somewhat immaterial. India only has 4 million cars and SUVs, about one for every 350 people, so it’s even less of a concern. By contrast, the USA has a car for every 1.2 people, including kids and the seniors who have forfeited their driving licenses.

In both the United States and Europe, driving a personal vehicle generally results in higher CO2e emissions per kilometer compared to flying. In the U.S., the average gasoline car emits between 250 to 300 grams of CO2e per kilometer, significantly more than the 150 to 250 grams of CO2e per kilometer generated by flying. In Europe, where vehicles tend to be more fuel-efficient, driving still produces more emissions, with an average of 200 to 250 grams of CO2e per kilometer, compared to 100 to 200 grams for air travel. Despite perceptions that air travel is a major contributor to carbon emissions, these figures underscore that driving is often the more carbon-intensive mode of transport per kilometer traveled.

The continued dip in US driving after COVID appears to be a silver lining of the pandemic. As the USA had by far the longest driving commutes and far more workplaces in industrial parks poorly served by anything remotely interesting or attractive as a destination, the severe contrast of working from home for American workers who were able to led to much stronger desire to remain working from home, at least in my reading. This appears to have led to a structural decline in US driving and hence passenger vehicle emissions despite the efforts of many employers to get employees back in the building.

Despite this, the remarkable outlier of the USA’s air travel, with the significant emissions that come from that mode of transportation, is still dwarfed by Americans driving around in their SUVs and pickup trucks. This is why a study published this year in Environmental International didn’t surprise me. It found that 92% of weekday trips in the United States were by car, compared to 45% in European countries and 30% in Asian countries.

The United States is a radical global outlier in terms of how its citizens get around. This is due to an unfortunate alignment of post-WWII circumstances. When US soldiers returned from the war, the GI Bill gave the white ones cheap mortgage options, which they used to move into newly built sprawling suburbs. They were able to get there because cars were already a somewhat big deal before the war, but after the war all of that excess manufacturing had to turn to something, and cars were a huge part of it. As for roads, the terror of a Soviet invasion led to the massive interstate network, which was to allow mobilization of military personnel and heavy ordnance anywhere in the country quickly. Finally, the USA had an intentional policy of distribution of its populace and industry during much of the Cold War, so that if the country were hit by nuclear weapons, enough Americans and industry would be left intact to pick up the pieces and “win” as a result.

Now America is left with a serious transportation and economic hangover from all of the profligate sprawl. Its citizens have to drive a lot further just to work, shop and run errands than anyone else in the world. Its sprawl means that interesting things are a long way from where most people live. Relatively few people live in population centers big enough to maintain them. The post-War period was affluent due to the combination of the New Deals building massive infrastructure and the continent not having had its infrastructure bombed back into the 19th Century. It was the industrial and manufacturing base for the world for a while.

It’s become a culture of flying and driving long distances regularly, a culture the rest of the world never bothered to develop. The densely populated cities of much of the world are full of fascinating things for people to do and see and eat and experience without ever having to drive or fly elsewhere.

As such, lessons from the United States in terms of transportation and some other decarbonization solutions are irrelevant to the rest of the world. It’s just not an important example, except of what not to become.

And it’s not like it can reverse this and build density that supports transit, walkability and bikeability, as much as a lot of Americans love the idea of those things. Decades of building sprawl and trillions of dollars spent on it will require generations to unwind, if they ever do.

One thing is clear from this assessment. The rest of the world is likely to be decarbonized before the USA manages it. Being such a radical outlier in terms of personal transportation, it’s by far the hardest to decarbonize. As its citizens have a rather huge sense of entitlement to flying and driving the absurd distances they do each year, they’ll remain the hardest customers to satisfy with low-carbon alternatives.

This is another reason that it’s quite possible China’s emissions will decline below US emissions in the coming decades while remaining a manufacturing and industrial hub for the world. Another, as I noted recently, is that China has been electrifying all aspects of its economy including transportation and industry and is now well above western levels of electrification, 30% compared to Europe’s 21% and the USA’s 14%. The trajectory in China is steeply upward, while the trajectory is barely rising in the West, despite decades of electrification being an obvious major climate solution.

To answer, then, the question at the beginning of this assessment, diverting passengers from aviation to rail is very much a wedge. It’s a wedge I leverage in my projections through 2100 of aviation and its a wedge the rest of the world is using. It’s just not a wedge even remotely available in the USA today and unlikely to be a wedge available in 20 or even 40 years.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy

.jpg)