Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Last Updated on: 25th February 2025, 11:37 am

Recently, I published a summary and expansion of critiques by Visa Siekkinen, an energy transition researcher now with Häme University of Applied Sciences in Finland, and Andrew Fletcher, Adjunct Industry Research Fellow at Griffith University in Australia, on hydrogen electrolyzer system capital expense estimates. Projections by organizations like IRENA, IEA, LUT, BNEF, and Europe’s industry association Hydrogen Council from five years ago were far too low initially, they have crept up annually, yet the projections are still far too low.

Someone tried to defend these organizations for these actually quite terrible estimates, claiming that electrolysis systems weren’t well understood and there weren’t good costs available in 2020, but the estimates and projections are indefensible. Let’s step through this.

The first industrial-scale alkaline electrolyzer was manufactured in 1869, marking the beginning of large-scale hydrogen production using electrolysis. These early systems, developed primarily for chemical and industrial applications, relied on liquid electrolyte solutions and nickel-based electrodes to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. Over the following decades, improvements in materials and engineering refined their efficiency and durability, enabling wider adoption in sectors such as ammonia production, petroleum refining, and steelmaking.

Alkaline electrolyzers have been operating continuously for over a century in industrial settings, with some individual units running for decades. They are commonly used in applications where a steady, large-scale supply of hydrogen is required, such as ammonia production, petroleum refining, and steelmaking.

One of the longest-running examples is the Norsk Hydro electrolyzer plant in Norway, which operated from 1927 until the early 2000s to produce hydrogen for ammonia synthesis using hydroelectric power. Similarly, industrial hydrogen production facilities in Germany, the Netherlands, and Canada have relied on alkaline electrolyzers for decades, particularly in chemical plants where uninterrupted hydrogen flow is critical. These systems are known for their durability, with many running continuously for 20–30 years with routine maintenance.

Proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers have been in commercial production since the 1960s, initially developed for space applications like the Apollo program, where they provided both hydrogen for fuel cells and oxygen for life support.

Siemens launched one of the first large-scale PEM power-to-gas projects in 2015 at its WindH2 facility in Germany. The system was designed to convert surplus wind energy into hydrogen, which could then be stored or injected into the natural gas grid.

Since 2014, Japan has deployed PEM electrolyzers in hydrogen refueling stations as part of its national hydrogen strategy. Companies like Iwatani and Toyota have led the effort, installing stations across major cities to support fuel cell vehicles such as the Toyota Mirai. Unlike alkaline electrolyzers, PEM systems can efficiently operate at high pressures, making them better-suited for vehicle refueling infrastructure. Their purported ability to quickly ramp up and down aligns with the unpredictable demand at fueling stations, suggesting a reliable hydrogen supply for Japan’s expected fleet of fuel cell cars.

California has been at the forefront of PEM electrolyzer deployment for fuel cell vehicles since 2015, rolling out hydrogen refueling stations to support the transition to zero-emission transportation. Several projects, including those funded by the California Energy Commission, have incorporated PEM technology to produce clean hydrogen onsite using renewable electricity.

In Norway, PEM electrolyzers have been deployed in off-grid renewable energy projects to store excess wind and solar power as hydrogen. One initiative, launched in the late 2010s, integrates electrolyzers with remote wind farms, allowing energy to be stored and transported to areas with high electricity demand.

That’s all to say that hydrogen electrolyzers as a technical component of a hydrogen manufacturing chemical plant are well understood, and while not fully commoditized were manufactured objects by the mid-2010s. By 2020, the cost of the electrolyzer component was well established, although the future cost was subject to debate.

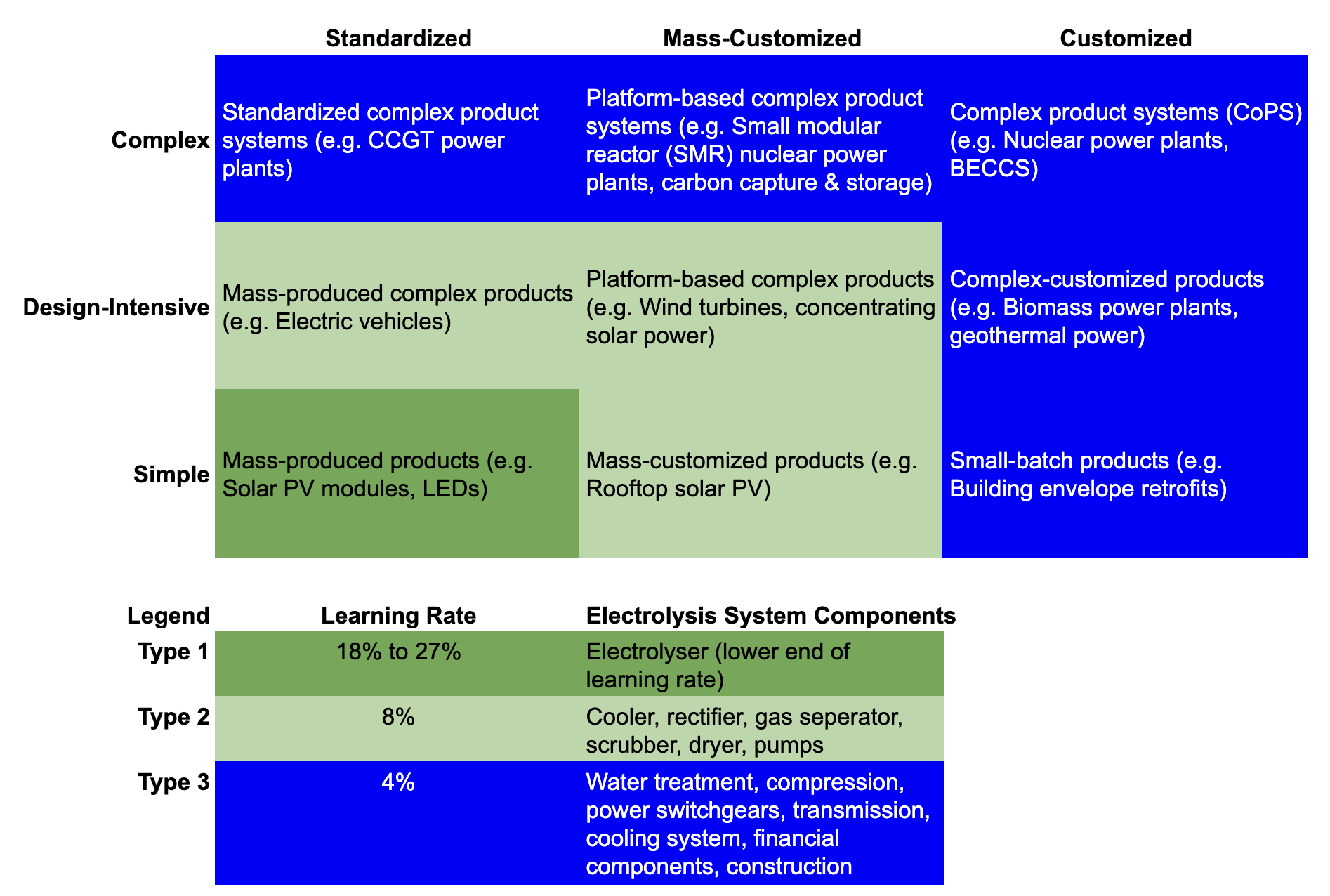

One of the graphics I included in the earlier article was this one. It’s an amalgamation of a 2020 framework by Malhotra and Ramboll perspectives on how it applies to electrolysis systems and some additional material referenced by Fletcher.

There is exactly one unique component in this compared to multiple other types of chemical manufacturing plants, the electrolyzer. The rest of the components were either fully commoditized in 2020 (and usually much earlier) or were already very mature, with low costs of adaptation for hydrogen applications. That’s why their learning rates — the reduction in cost due to doubling of manufacturing volumes, also referred to as Wright’s Law — are much lower.

Applying Wright’s Law to chemical manufacturing plants requires an understanding of how cost reductions occur as production scales. Unlike mass-produced goods like solar panels or batteries, chemical plants combine both manufactured components and large-scale infrastructure, each with different learning rates. Defining the right learning unit is crucial, whether it’s megawatts of electrolyzer capacity, metric tons of annual production, or total installed plant capacity.

Different parts of a plant follow distinct learning curves. Core process units such as reactors, electrolyzers, and separation systems may benefit from efficiency improvements and better materials. Balance-of-plant components like compressors and heat exchangers are already commoditized, meaning cost reductions will come from standardization rather than steep learning effects. Advances in automation and digital controls could further reduce costs through process optimization.

Learning-by-doing must also be distinguished from economies of scale. Modular chemical plants, such as small-scale ammonia units or electrolyzer farms, may see faster cost declines as they are repeatedly manufactured. Large custom-built plants experience more gradual reductions, as their cost savings depend on scaling rather than iterative production improvements. Process innovations, such as better catalysts or high-efficiency membranes, can drive cost declines independent of scale.

Large plants, however, often have optimum scale for individual processes, which drives down costs substantially. Modularity requires getting the module scale right. Professor Bent Flyvbjerg, whose 2023 book How Big Things Get Done was at the top of or on most best business books of the year and included some of my material in chapter nine, What’s Your Lego?, extols the virtues of modularity. Paul Martin, who I referenced in my article that drew the defense of IEA et al and someone who has been in the business of designing and building modular chemical process engineering plants including for hydrogen applications for decades, adds a very insightful nuance on this point in his piece WHY Big Things Get Done, which focuses on scaling the modules appropriately. Basically, a bunch of unnecessarily tiny things aren’t optimal compared to a smaller number of appropriately scaled things.

Supply chain constraints can also impact learning rates. Limited availability of key materials, such as iridium for PEM electrolyzers or nickel for catalysts, could slow cost reductions. Manufacturing bottlenecks and regional cost differences further complicate global learning curves. Policy incentives, financing conditions, and regulatory hurdles may also influence cost trajectories, either accelerating or distorting true learning effects.

Validating projected cost declines requires comparing them to real-world data. Historical trends in petrochemicals, refining, and industrial gases provide useful benchmarks. Early pilot projects should be assessed against modeled learning curves, ensuring that projected cost declines match actual deployment rates. In the end, meaningful cost reductions will depend on both technological progress and real market adoption, not just theoretical expectations.

The cost structure of chemical manufacturing plants has evolved alongside their technological advancements, with early industrial facilities setting the stage for modern cost considerations. The first large-scale chemical plants, such as those based on the Leblanc process for soda ash in the 1790s, were capital-intensive due to the need for custom-built furnaces, batch processing, and inefficient material handling. These early plants had high raw material and labor costs, making scaling difficult.

By the mid-19th century, cost efficiencies improved with the Solvay process, which replaced the expensive Leblanc method. Continuous processing reduced labor costs, while the ability to recover byproducts improved material efficiency. The shift from batch to continuous operations marked a key moment in chemical plant cost reduction, setting a precedent for modern economies of scale.

The Haber–Bosch ammonia plant, built in 1913 in Oppau, Germany, revolutionized chemical manufacturing economics. This facility introduced high-pressure, high-temperature synthesis, requiring specialized materials and engineering expertise, which increased capital costs. Its ability to operate continuously and at scale significantly lowered per-unit production costs, justifying the upfront investment. This shift toward process intensification continues to define modern chemical plant economics.

Today’s chemical plants integrate advanced automation, modular construction, and digital controls, further optimizing costs. Raw material pricing, supply chain constraints, and regulatory compliance remain major cost drivers. While modern plants benefit from learning curves and economies of scale, their capital intensity means accurate cost assessments must distinguish between genuine cost reductions and external market fluctuations.

This is all to say that we’ve been costing chemical manufacturing plants for literally centuries and there’s absolutely nothing exotic about figuring out what components to include in the costing, and for hydrogen electrolysis plants there’s nothing difficult to figure out. It’s just a matter of asking the firms which are manufacturing electrolyzers, including PEM electrolyzers, the only remotely new component, what their list price of the manufactured components was, and looking at all of the other chemical manufacturing plants that were similar to figure out the outside view.

The outside view is an evidence-based forecasting approach that predicts outcomes by comparing a project to a reference class of similar past projects rather than relying on case-specific assumptions or expert judgment. The outside view of chemical manufacturing plants suggests that cost overruns and delays are the norm rather than the exception, with historical projects routinely exceeding initial estimates due to unforeseen complexities. Applying Flyvbjerg’s reference class forecasting (RCF) method requires anchoring cost projections in empirical data from comparable projects rather than relying on optimistic assumptions. By analyzing a broad dataset of past chemical plants, RCF adjusts for systematic biases, incorporating real-world cost trajectories instead of theoretical learning rates.

RCF was first formally asserted by Bent Flyvbjerg in 2003, based on earlier work in behavioral economics and decision-making biases. Flyvbjerg built on the concepts of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, particularly their research on the planning fallacy, which showed that project planners systematically underestimate costs and timelines.

Once again, that’s 2003, 17 years before the ‘visionary’ projections of really low electrolysis manufacturing facilities and their future costs were being projected and used as the basis of policy decisions.

By 2020, electrolyzer technology was already well understood, with 150+ years of operational history for alkaline electrolyzers and decades of commercial PEM deployments. The balance-of-plant components, including compressors, storage, and power electronics, were already commoditized industrial equipment with established learning rates. Analysts also had access to cost data from past electrolysis projects, chemical manufacturing plants, and broader industrial scaling trends.

RCF had been established for nearly two decades, providing a proven method to counteract the planning fallacy and optimism bias in cost projections. Historical experience with cost overruns in renewable energy, industrial gas plants, and infrastructure projects should have been incorporated into hydrogen electrolysis estimates. Yet, many cost models followed wishful back-calculations, assuming hydrogen had to reach a competitive price and then shaping cost curves to fit that assumption—a clear violation of RCF and the outside view.

The fundamental issue was not a lack of tools or data, but a failure to apply them correctly, driven by policy-driven narratives, model optimism, and overconfidence in learning curves. If analysts had grounded their projections in historical cost data, industrial learning rates, and RCF principles, estimates in 2020 would have been significantly more realistic.

So, why were so many organizations and analysts blinded by cognitive biases? For over two decades, techno-economic analyses have highlighted the fundamental limitations of hydrogen scaling, yet optimistic projections persist. Instead of starting with realistic industrial cost trends, analysts begin with the price hydrogen needs to reach for competitiveness and then manipulate assumptions to justify that outcome—breaking the laws of physics and economics in the process.

I’ve tracked cost projection after cost projection, and the same pattern emerges. Organizations like JRC, ICCT, and PIK have repeatedly produced flawed estimates, driven by collective biases and blind adherence to model outputs. Rather than grounding forecasts in historical industrial cost trends, they rely on theoretical learning rates that don’t align with the realities of large-scale chemical manufacturing. Electrolyzers are not consumer electronics; they follow industrial scaling principles, not Moore’s Law.

This issue has been clear for decades. I provided technical edits to Joe Romm’s 20th-anniversary edition of The Hype About Hydrogen, which debunked many of the same exaggerated claims that persist today. I’ve discussed similar analyses with Bruce McCabe, PhD, who did the napkin math around the same time, and my first deep dive into the subject was published last decade. Experts like Paul Martin were fully aware of these challenges as far back as 2000. The barriers to cost reduction—capital intensity, material constraints, and slow-moving industrial processes—have never been a mystery.

Organizations predicting steep declines in hydrogen electrolysis capex have no defense because they had decades of historical cost data, established industrial learning rates, and proven forecasting methodologies like RCF at their disposal but failed to apply them correctly. Electrolyzer technology has been commercially deployed for over a century, and its balance-of-plant components are mature industrial equipment with well-understood cost structures, leaving little room for the kind of rapid cost declines seen in emerging technologies like solar or batteries.

Despite this, groups like JRC, IEA, CSIRO, HC, and PIK ignored these realities, instead relying on model-driven assumptions that start with the price hydrogen needs to reach for competitiveness and then work backward to justify it—violating both economic principles and historical precedent. Their projections are not just overly optimistic, but fundamentally flawed, driven more by policy goals than by grounded industrial analysis.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy