Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

The airline industry is responsible for about 3% of all greenhouse emissions. At the International Air Transport Association annual meeting in 2021, a resolution was passed by IATA member airlines committing themselves to achieving net zero carbon emissions from their operations by 2050. This pledge brought air transport in line with the goals of the 2015 Paris climate agreement. To succeed, it will require the successful development of sustainable aviation fuel to slash the emissions for jet engines by 80% or more.

There are two keys to meeting the IATA goal set in 2021. The first is switching from Jet A, a highly refined form of kerosene that is used to fuel today’s jet engines, to sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). The second is converting from today’s fleet of commercial aircraft to next generation planes that are 20 to 30% efficient. There are a few challenges to making those objectives happen. Today there is only enough sustainable aviation fuel available to supply about 0.5% of the demand. In addition, airplane manufacturers have so many orders for next generation, more fuel efficient aircraft, that it may take a decade or more to fill all the orders.

This week, Air New Zealand became the first airline to announce it was unable to meet its emissions reduction goals and will withdraw from the industry’s net zero by 2050 pledge. The airline had hoped to reduce its emissions 29% by 2030, but said that goal was now unrealistic. Air New Zealand CEO Greg Foran told The Guardian, “In recent months, and more so in the last few weeks, it has become apparent that potential delays to our fleet renewal plan pose an additional risk to the target’s achievability. It is possible the airline may need to retain its existing fleet for longer than planned due to global manufacturing and supply chain issues that could potentially slow the introduction of newer, more fuel efficient aircraft into the fleet.”

Slow Going For Sustainable Aviation Fuel

The Guardian adds that the much touted “sustainable aviation fuels” are way off track in their quest to replace current fuels in a time frame needed to avert dangerous climate change. The most recent reports have found there is now “no realistic or scalable alternative” to standard kerosene-based jet fuels. The new fuels are made of biomass, including crops, waste oil, and forestry and agricultural waste. However it is doubtful that enough SAF can be produced to meet the demand of the aviation industry while not using so much arable land that the ability to grow enough food for over 8 billion people is diminished.

Bloomberg reports that Air New Zealand may only be the first of many airlines to back away from their emissions reduction promises. Cathay Pacific Airways Ltd. said earlier this month the enormity of the task had become clear after talks with about 50 potential suppliers. “We have really witnessed how difficult it is for the SAF industry to take off,” Grace Cheung, Cathay’s general manager of sustainability, said in an interview. Last year, Akbar Al Baker, the CEO of Qatar Airways at the time, said even the industry’s 2050 net zero targets were unattainable.

SAF, made from waste fats or agricultural feedstock, could cut emissions by almost 80% if it fully replaces jet kerosene, according to airline industry sources. They are betting their sustainable future on SAF because other fuel sources such as hydrogen or electric batteries remain far from commercialization. But even with the commitment to SAF by the airline industry, IATA in June cut its estimates for total SAF production in 2030 after finding that many projects were behind schedule. It said output had to increase by a factor of 1,000 by 2050 — a rate of increase that is viewed as highly unlikely to happen.

Airline emissions are predicted to increase by 82% by 2050, says BloombergNEF. That would see the industry’s share of global carbon dioxide pollution jump to about 6.7% — nearly triple what it is today. When it comes to cutting emissions, it’s time for airlines to acknowledge the limits of what’s possible, according to Emirates President Tim Clark. “We’ve got to have a grown-up conversation about what is achievable. We shouldn’t give up on it. We should just inject a sanity check.”

United To Use Sustainable Aviation Fuel At O’Hare Airport

This week, United announced it will purchase up to 1 million gallons of sustainable aviation fuel at its O’Hare airport hub in Chicago — the first US airline to do so, according to USA Today. According to United, O’Hare is the first U.S. airport outside of California that will have a portion of its fuel supply be filled by SAF. The airline said the initiative is made possible by tax credits recently passed in the state of Illinois.

“This is what happens when innovation, leadership and policy come together,” United president Brett Hart said in a statement. “While the market for SAF is still in its infancy, there is a huge opportunity today for airlines and policymakers to work together to support its continued growth. SAF at O’Hare was made possible thanks to Governor Pritzker and the Illinois Legislature passing tax incentives.” Today, jetBlue made a similar announcement regarding its operations at JFK airport in New York, according to Reuters.

Trouble In Paradise

In a report in May, the World Resources Institute issued a warning about how federal tax credits for sustainable aviation fuels were being handled after the Biden administration extended those credits to include fuels made from corn ethanol or vegetable oils. The policy “flies in the face of stated climate goals.” the WRI said.

“The guidance, finalized on April 30, opens the door to tax credits for fuel made from corn ethanol or vegetable oils — despite strong evidence that these crop-based ‘biofuels’ actually increase net emissions while diverting valuable cropland away from food production.

“This would be a sharp turn in the wrong direction. US domestic flights were responsible for 150 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions in 2019, representing almost 3% of the country’s total emissions. With air travel projected to grow rapidly, aviation emissions are expected to roughly double by 2050, both in the U.S. and globally. And that’s before factoring in a heavier reliance on unsustainable biofuels.

“The Biden administration’s final guidance for the SAF tax credit bows to pressure from the biofuels industry rather than adhering to the best available science for modeling life cycle airline emissions, which shows that — instead of being a climate solution — crop-based aviation fuels are even worse than their fossil fuel alternatives and could increase hunger and habitat destruction.

“Many scientists and international regulatory bodies have concluded that growing crops to make aviation fuel does not reduce emissions on a full life cycle basis from crop production through to processing and consumption. This is because it displaces food crops, which drives the expansion of cropland into forests and grasslands both in the US and globally to compensate for lost food production. Converting forest or grassland to cropland releases stored carbon and severely reduces carbon sequestration on that land in the future.”

Sustainable Aviation Fuel From Bio-Sludge

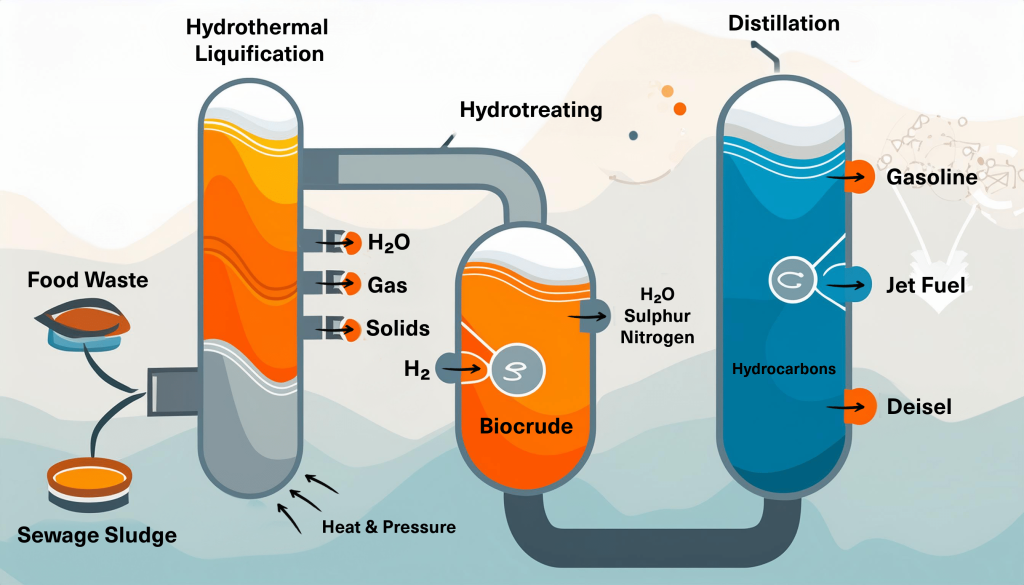

What follows may make some readers a little squeamish, but bear with us. Firefly Green Fuels in the UK says it has found a way to make sustainable aviation fuel from sewage sludge, The heart of Firefly’s project is a process known as hydrothermal liquefaction. Think of it as a pressure cooker for excrement. Simon Black, head of circular economy at Anglian Water, which will supply the “biosolids feedstock,” tells Tech Informed that the journey begins with wastewater from households and various businesses.

“It then goes through the collection network, miles and miles of pipework and pumping stations, to bring it to water recycling centers. They then separate the solids from the water to effectively clean the water and put it back into the environment.” The separated solids undergo anaerobic digestion, a biological process in large tanks maintained at around 37°C. Unlike chemical processes, this stage relies on the activity of microbes to break down the organic matter. The separated solids, rich in organic matter, will eventually be converted into fuel.

Firefly’s innovative approach utilizes hydrothermal liquefaction to emulate the natural geological processes that produce crude oil, but at a much faster rate. Applying high temperature and pressure converts the bio-sludge into bio-crude oil, transforming the solid waste into a liquid form that can then be refined into SAF.

Black explains the advantage of this process is its ability to guarantee the consistency of the sludge. That is crucial for any subsequent conversion processes, like turning the sludge into SAF. “The benefit of using sewage sludge is that it has been through a very advanced form of anaerobic digestion and leaves the final material very consistent because it’s so highly treated, unlike livestock waste,” he says.

One of the main problems with producing SAF using conventional feedstocks, such as cooking oil and animal fats, is that they are costly and limited in availability. While plant by-products can also be an alternative, the excessive use of agricultural land and forests to obtain large amounts of biomass can negatively impact ecosystems and biodiversity.

Paul Hilditch, co-founder of Firefly, explains that the advantage of the SAF technique used in its process is that it is more affordable and scalable. “There’s enough biosolids in the UK to produce more than 200,000 tons of SAF. That’s enough to satisfy about half of the mandated SAF demand in 2030. We need the other routes to SAF, too. However, this new route has the potential to move the needle and make a significant contribution to UK SAF production. And not just the UK. Anywhere in the world where there are people, there is poo.”

According to Hilditch, scientists estimate the average human produces 30 kilograms of dry-weight waste per year, which could produce over 14 billion liters of SAF. Another by-product of this process is biochar, a charcoal-like substance that can be used for carbon sequestration and could be used in construction or agriculture. Firefly’s venture facilitates a circular economy where waste is not simply discarded but becomes a valuable resource. They say this model promotes efficient resource use, minimizes waste, and stimulates economic growth by creating new industries and job opportunities related to SAF production.

The first Firefly facility at Harwich in the UK site will use existing infrastructure previously used for traditional crude oil and gas refining, saving production time, costs, and emissions. When complete, it will produce 100,000 tons of sustainable fuel per year. It’s backed by significant investments from key industry players, including [we swear we are not making this up] Wizz Air, which recently committed to fueling 10% of its flights with sustainable fuel by 2030.

Yvonne Moynihan, ESG officer at Wizz Air, described the partnership with Firefly as “a marriage of low costs.” This refers to how Firefly’s SAF, “the cheapest and most abundant feedstock,” is a perfect match for an airline focused on low costs and fares. The Hungarian airline has ordered up to 525,000 tons of Firefly’s fuel over the next 15 years, potentially worth hundreds of millions of pounds.

The Takeaway

The airline industry may have good intentions when it comes to reducing emissions, but making those reductions actually happen is a daunting challenge. Sustainable aviation fuel, like carbon capture and carbon offset credits, looks nice in glossy corporate brochures but is actually hard to do. While the concept is laudable, the proof of the pudding will be whether it can made in sufficient quantities and at a price that is competitive with good old fashioned Jet A. CleanTechnica readers know the difference between promises — better, cheaper batteries, autonomous cars, faster grid connections for renewable energy — and reality. Taking ideas and turning them into commercial successes is hard work, with many detours and dead ends along the way.

The Firefly technology is interesting, but costs are yet to be determined, so the jury is definitely still out on that idea. Now if only someone could figure out how to take animal farming waste and process it into sustainable aviation fuel, that would give a whole new meaning to the expression, “When pigs fly.”

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy