This week for Ask an Economist, I have a question from retired CPA, Nicholas G. He asks, “why is so much attention paid to the somewhat artificial and easily manipulated unemployment number instead of a “hard” number such as the number/rate of employment amongst the working age population?”

To answer this, we’ll begin by discussing some of the terms used when discussing unemployment in the US. Then we’ll move into shortcomings of the unemployment rate that makes headlines, and I’ll discuss the ups and downs of some alternative measures.

To Count, or Not to Count?

A few weeks ago, I wrote a piece on how the government quantifies inflation. In that article, I pointed out that while it may sound like a good idea to simply consider the price of all goods and services, that sort of statistic would include information about prices for a lot of goods that most people don’t care about (think yachts and fighter jets). Instead, inflation statistics try to mainly focus on relevant prices.

Similarly, it may be tempting to say that the best and least arbitrary way to measure employment would be to simply compare the total number of people in the country who have jobs to those who don’t have jobs. But this number alone might be deceptive. Why?

Consider a fictional country called FeeLand. FeeLand has 100 people, 60 of whom have jobs, and 40 of whom do not have jobs and are not looking. Now imagine ten babies are born. Before the babies, 60% (60/100) of the total population had a job. Now only about 55% (60/110) have a job.

So it looks like employment in this country has gotten worse, but obviously it isn’t a problem is babies are unemployed, so nothing has really changed. Likewise if people end up in the hospital and can’t work, it doesn’t really make sense to think of this as an employment problem.

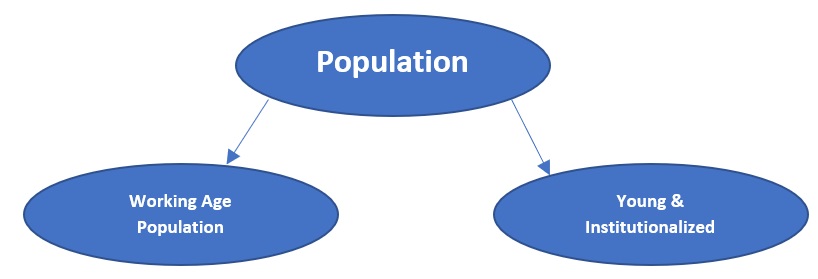

In order to deal with these issues economists break up those people old enough (16+) and free to work. This group is called the working age population. In contrast, the rest of the population is labeled as the young and institutionalized, and aren’t discussed much with reference to employment issues

So here is the breakdown.

Figure 1—The Working Age Population

So likely you agree that baby unemployment is not a huge problem, and you’re on board with focusing simply on the percent of the working age population who are employed.

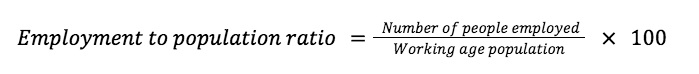

If that statistic seems important to you, you’re in luck. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) collects this information and calls it the employment to population ratio. In math terms it is:

While this number seems certainly more useful than considering the entire population, it still has some issues if we’re worried about the problems associated with unemployment. Why?

In the United States in 2016, 27% of mothers were stay-at-home moms. Is this a problem? I certainly don’t think so. Without stay-at-home moms, I think the country would be a much worse place.

This is only one example, but consider another—students. Many people above the age of 16 do not have jobs because they’re focusing on increasing their future productivity via education. Is that a problem? Certainly not.

Let’s return to our FeeLand example. We had 100 people in the working age population, 60 of whom have jobs. Imagine of those 60, two leave their careers to pursue a degree and three leave because they value the time at home with kids more than the money they currently earn from working. So now, only 55 of the 100 working age population are employed.

The employment to population ratio fell from 60% to 55%. But is this fall bad? Certainly not.

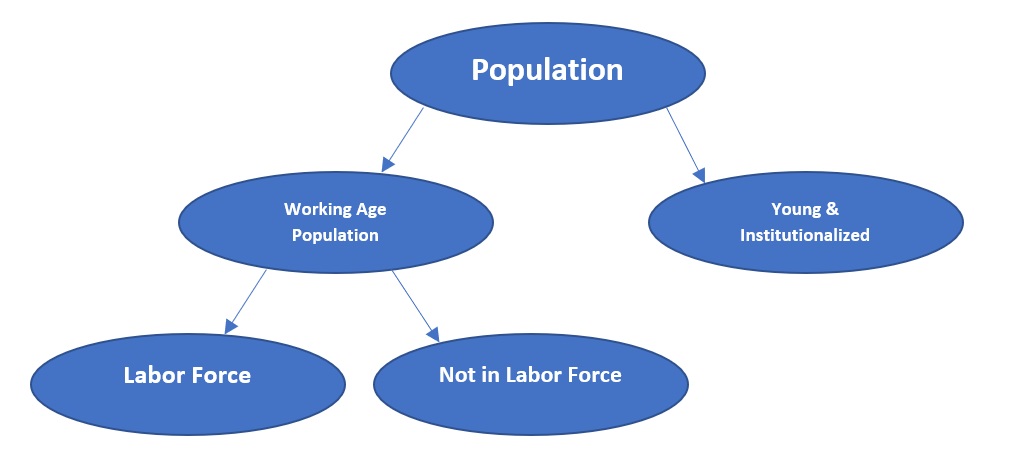

The BLS deals with this fact by breaking the Working Age Population into two more groups. Those who have a job and those who are currently looking for a job are called members of the Labor Force whereas those who aren’t looking for jobs (i.e. students) are described as Not in the Labor Force.

Here is the new breakdown.

Figure 2—The Labor Force

The BLS takes this Labor Force number and uses it to calculate what percent of the Working Age Population either has a job or is looking for a job. This is called the Labor Force Participation Rate.

In math terms it is:

Unemployment vs. Labor Force Participation Rate

Breaking the population into the Labor Force allows the BLS to differentiate between people who don’t want jobs and people who do want jobs but can’t find them. This latter category is how the BLS defines the unemployment rate.

In order to come up with the unemployment rate the BLS considers what portion of the Labor Force is currently unemployed. In other words, what percentage of the labor force has a job currently, and what percentage does not a have a job but wants one. Here is the final breakdown.

Figure 3—Unemployment

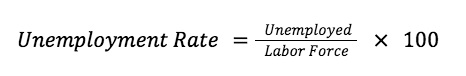

So, in order to come up with the employment rate, the BLS takes the total number of unemployed divided by the total number of the labor force. Mathematically it is:

This number is good, because it ignores the fact that some people are not employed for perfectly good reasons. But it isn’t without its downsides. To understand the issues with the unemployment rate, let’s go back to our example of FeeLand.

So far in FeeLand, there is a total population of 110 with 10 of those people being babies. Therefore the Working Age Population is 100. Of the remaining 100, we know that 55 are employed (and therefore in the labor force) and 5 are not in the labor force. That leaves us with 40 members of the working age population we haven’t discussed. For sake of ease, let’s assume all 40 of those people are not in the labor force.

So FeeLand has 55 of 100 working age people in the labor force and 45 of 100 not in the labor force.

At this point, though, you may notice something peculiar about our example. As things stand in FeeLand, everyone who wants a job has one. In other words, there are 55 people in the labor force and all 55 are employed. This country has a 0% unemployment rate and a 55% labor force participation rate.

Let’s see what happens when things change. Imagine a recession hits and causes mass layoffs. Imagine of the 55 employed workers, 15 lose their jobs and start searching for new jobs. Now there are 15 unemployed workers with a labor force of 55 for an unemployment rate of 27% (15/55)!

Things look bad in FeeLand. Now this is where the rubber hits the road for problems with the unemployment rate as a metric.

We’ll stipulate that after months of searching for a new job, 5 of the unemployed workers quit searching. They drop out of the labor force completely. If that’s the case we now have only 10 unemployed workers (because you are only considered unemployed if you are actively searching for work) and the labor force is now 50 people. The unemployment rate actually fell to 20% (10/50).

So workers giving up looking for a job actually improves the unemployment rate.

Notice, though that the labor force participation rate actually captures this negative change. Previously 55 of the 100 working age population were in the labor force for a participation rate of 55%. Now that rate is down to 50% (50/100).

For this reason, some argue that the labor force participation rate is really a better metric for telling whether times are getting better or worse. But we should be careful.

Remember, the labor force participation rate also falls when people decide they’d prefer to be stay-at-home parents or pursue an education. These decisions aren’t bad, but if we consider a falling labor force participation rate to be “bad” then we will think of them this way.

On the other hand, the unemployment rate doesn’t capture the issue of discouraged workers. You might wonder if we can separate discouraged workers from other declines in the labor force participation rate, and there are attempts to do that, but it’s difficult because often when people lose their jobs they decide a second best option is to do something like go back to school. How do we separate that from those who chose to do that as a first best option?

Context Matters

All of this is to say that there is no perfect metric for employment as it relates to the health of the economy as a whole. Context is necessary for determining whether changes in these metrics are good or bad.

Is higher unemployment bad? Probably not if it’s due to people being encouraged enough to rejoin a labor force they previously left.

Is more labor force participation good? Probably not if it’s due to a spouse entering the labor force because the couple can no longer survive on the income of one amidst inflation.

Is labor force participation rate or unemployment a better gauge of understanding how well a country is recovering from a recession? It depends on the context.

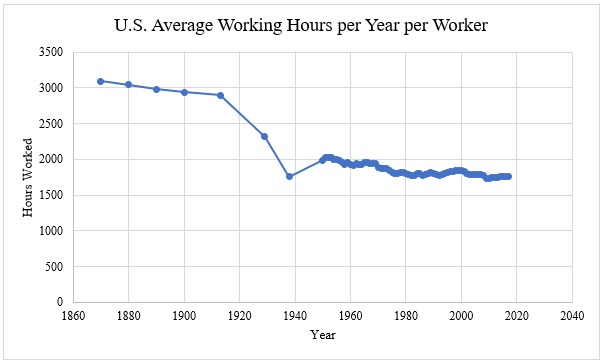

To give one last example, my coauthor Rosolino Candela and I are currently doing work that considers economic trends over time. One thing we want to see is if people have more or less leisure time than they did decades ago. Look at this graph made with data from OurWorldInData.

Figure 4—US Average Annual Working Hours per Worker

You can see that in the US, over time, the number of hours worked has decreased pretty consistently over time. In the context of the last century and a half as a whole, this is a good thing. You can work less hours today for a better standard of living than people in the prior two centuries.

But context matters. Look at 1938 in the US. They worked less hours then than we do now! And hey, it seems like the 1920s and 1930s were overall great for leisure time. Ripped of all context, this could be your takeaway.

But hours worked, like any metric, is deceptive without context. As we all know, the reason hours worked declined so much in the 1920s and 1930s was due in large part to the Great Depression. It certainly was no vacation.

In conclusion, to paraphrase my prior article on quantifications of inflation, despite the politicking that goes on with the unemployment rate and the labor force participation rate, I think both have a place in helping us talk about what’s going on, insofar as we need economic statistics at all.

Courtesy of Fee.org

*********