Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Dozens of luxury beachfront condos and hotels in Surfside, Bal Harbour, Miami Beach, and Sunny Isles are sinking into the ground at rates that were “unexpected,” with nearly 70 percent of the buildings in northern and central Sunny Isles affected, research by the University of Miami found. The study, published December 13, 2024, in the journal Earth And Space Science identified a total of 35 buildings that have sunk by as much as three inches between 2016 and 2023, including the iconic Surf Club Towers and Faena Hotel, the Porsche Design Tower, The Ritz-Carlton Residences, Trump Tower III, and Trump International Beach Resorts. Those buildings accommodate tens of thousands of residents and tourists. Some have more than 300 units, including penthouses that cost millions of dollars.

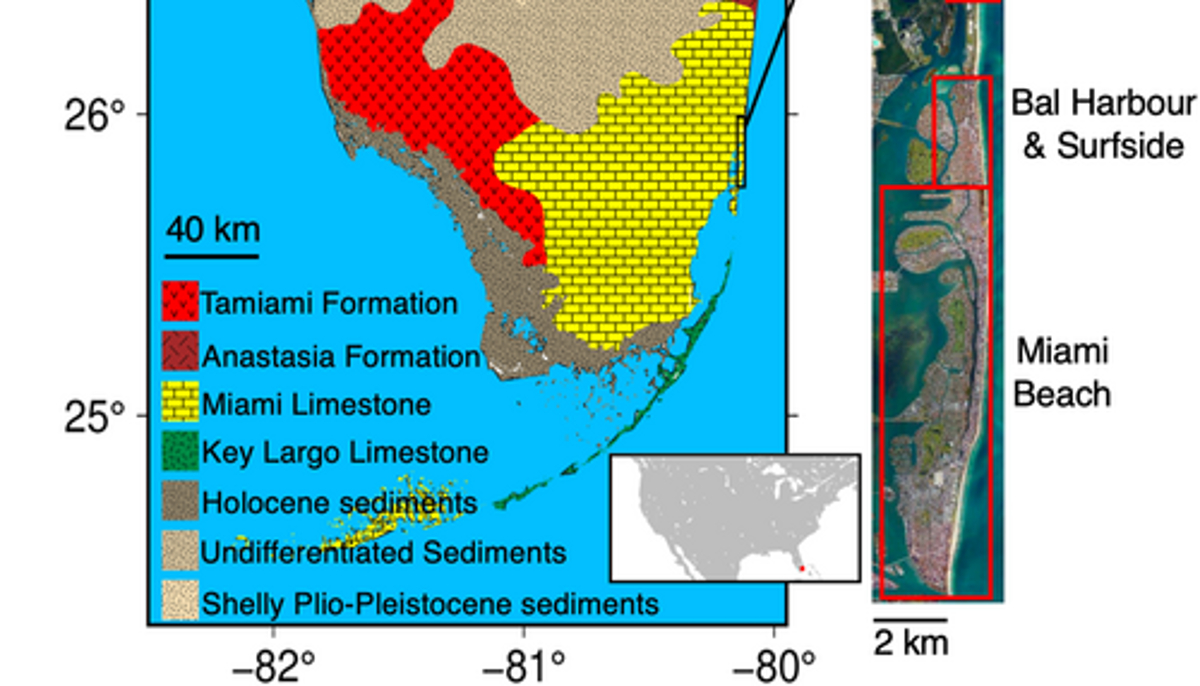

“Almost all the buildings at the coast itself, they’re subsiding,” Falk Amelung, a geophysicist at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric and Earth Science and the study’s senior author, told the Miami Herald, “It’s a lot.” Preliminary data also shows signs that some buildings along the coasts of Broward and Palm Beach are sinking. Experts called the study a “game changer” that raises a host of questions about development on vulnerable barrier islands. For starters, experts said, this could be a sign that rising sea levels, caused by the continued emission of greenhouse gases, is accelerating the erosion of the limestone on which South Florida is built.

“It’s probably a much larger problem than we know,” Paul Chinowsky, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Colorado Boulder, told the Herald. Initially, researchers looked at satellite images that can measure fractions of an inch of subsidence to determine whether the phenomenon had occurred leading up to the collapse of Champlain Towers in Surfside, the 2021 catastrophe that killed 98 people and led to laws calling for structural reviews of older condos across the state. The researchers did not see any signs of settlement before the collapse, “indicating that settlement was not the cause of collapse,” according to a statement. But they did see subsidence at nearby beachside buildings both north and south of it.

“What was surprising is that it was there at all, so we didn’t believe it at the beginning,” Amelung said, explaining that his team checked several sources that confirmed the initial data. “And then we thought, we have to investigate it.” In total, they found subsidence ranging between roughly 0.8 and just over 3 inches, mostly in Sunny Isles Beach, Surfside, and at two buildings in Miami Beach — the Faena Hotel and L’atelier condo — and one in Bal Harbour. It’s unclear what the implications are or whether the slow sinking could lead to long-term damage, but several experts told the Herald that the study raises questions that require further research as well as a thorough on-site inspection.

“These findings raise additional questions which require further investigation,” Gregor Eberli, a geoscience professor and co-author of the study, said in a statement. Lead author Farzaneh Aziz Zanjani pointed to the need for “ongoing monitoring and a deeper understanding of the long term implications for these structures.” Though the vast majority of affected buildings were constructed years or decades before the satellite images were taken, it is common for buildings to subside a handful of inches during and shortly after construction — a natural effect as the weight of the building compresses the soil underneath. And sinking doesn’t necessarily create structural issues.

That Sinking Feeling In Miami

“As long as it’s even, everything’s fine,” Chinowsky said, placing his hands next to each other. “The problems start when you start doing this,” he said, then moving one hand down faster than the other. Such uneven sinking, known as differential subsidence, can cause significant damage to buildings. “That’s where you can get structural damage,” he said. More research is needed to determine whether the buildings are sinking evenly or not. “Sometimes it can be dangerous, sometimes not. It will have to be evaluated,” said Shimon Wdowinski, a geophysicist at Florida International University. He worked on a different 2020 study that showed that the land surrounding the Champlain Towers — not the buildings themselves — had been subsiding back in the nineties. Though, that alone couldn’t have led to the collapse.

For the 35 buildings shown to be sinking in the University of Miami’s study, he said, the next step is to check the integrity and design plans. “If there is differential subsidence, it could cause structural damage, and it would need immediate attention,” he said. Cracks in walls, utilities that are breaking, or doors and windows that don’t shut as easily as they used to are all signs of differential subsidence, said Hota GangaRao, a professor of civil engineering and the director of the constructed facilities center at West Virginia University. “In some extreme scenarios, the buildings at some point sink much more dramatically with time,” he said. If that subsidence is differential, “then it is very, very serious,” he said.

Some settlement appears to have started right around the time the construction of new buildings nearby began, and when vibration might have caused layers of sand to compress further. The pumping of groundwater that seeps into construction sites could also cause sand layers to shift and rearrange. Though there appears to be a strong link to nearby construction for some buildings, it is unlikely to be the only explanation for the 35 sinking buildings, as some settlement had started before any construction began nearby and persisted after construction ended. “There’s no sign that it’s stopping,” Amelung said of the settlement.

Barrier Islands Are Tricky

Experts also pointed to the impact the emission of fossil fuels and the resulting warming of the climate is having on the overall stability of Miami-Dade’s barrier islands. For one, rising sea levels are now encroaching on sand and limestone underneath the buildings. That could lead to the corrosion of the pillars on which highrises stand. Stronger waves, heavier rainfalls, and more sunny day flooding could also add to the erosion of the limestone that all of South Florida is built on, Chinowsky said. Already a soft rock that is riddled with holes and air pockets, further erosion could destabilize the base of most constructions. “I would expect that they would see this all throughout the barrier islands and on into the main coastline — wherever there is limestone, basically,” he said. “That’s what makes the whole South Florida area so unique, because of that porous rock, the limestone, all that action is happening where you can’t see it, and that’s why it’s never accounted for to this level.”

For readers who like more technical information, here is the abstract of the study:

This study utilizes Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) to examine subsidence along the coastal strip of the Miami barrier islands from 2016 to 2023. Using Sentinel-1 data, we document vertical displacements ranging from 2 to 8 cm, affecting a total of 35 coastal buildings and their vicinity. About half of the subsiding structures are younger than 2014 and at the majority of them subsidence decays with time. This correlation suggests that the subsidence is related to construction activities.

In northern and central Sunny Isles Beach, where 23% of coastal structures were built during the last decade, nearly 70% are experiencing subsidence. The majority of the older subsiding structures show sudden onset or sudden acceleration of subsidence, suggesting that this is due to construction activities in their vicinity; we have identified subsidence at distance of 200 m, possibly up to 320 m, from construction sites. We attribute the observed subsidence to load-induced, prolonged creep deformation of the sandy layers within the limestone, which is accelerated, if not instigated, by construction activities.

Distant subsidence from a construction site could indicate extended sandy deposits. Anthropogenic and natural groundwater movements could also be driving the creep deformation. This study demonstrates that high-rise construction on karstic barrier islands can induce creep deformation in sandy layer within the limestone succession persisting for a decade or longer. It showcases the potential of InSAR technology for monitoring both building settlement and structural stability.

The Takeaway for Florida

Construction in Miami and nearby areas continues at a breathtaking pace. What this study suggests is that new construction can disturb the foundations of nearby existing buildings in an area where arguably no major construction should be permitted due to the instability of the sand and limestone substrate underneath. But this is some of the most desirable real estate in America, so proceeding with caution is not very likely.

Much of South Florida consists of limestone, which dissolves slowly in saltwater. That’s a long-term problem for which there are no easy solutions. But there is a solution to over-building — don’t do it, especially in Miami and neighboring communities. Now to see whether anyone will pay the slightest attention to the science. The odds are, nobody will until another disaster strikes the area. There is just too much money to be made by continuing to build in this area to even think about stopping. There is a lesson to be learned in there somewhere.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy