It appears more and more likely that the Federal Reserve is poised to completely abandon any pretense of fighting inflation, despite the fact CPI remains well above the 2 percent target.

The Fed has already paused interest rate hikes, and most analysts expect rate cuts later this year. Now, the financial news networks have started chattering about the possibility of the central bank either slowing or even ending its balance sheet reduction plan.

Speculation about the end of balance sheet reduction started early this month with the release of the FOMC meeting minutes. They revealed that some committee members thought they needed to “begin to discuss” technical factors that would direct their decision to slow the runoff of maturing bonds from its balance sheet.

Dallas Fed President Lorie Logan was the first committee member to talk about it publicly, saying that the central bank should begin tapering the runoff of bonds from its balance sheet when its reverse-repo facility fell below a certain level.

More recently, Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller said it would be “reasonable” to start thinking about tapering off quantitative tightening this year.

If the Fed has done enough to slay price inflation, ending balance sheet reduction would make sense. But has it really done enough?

FED BALANCE SHEET REDUCTION IN PRACTICE

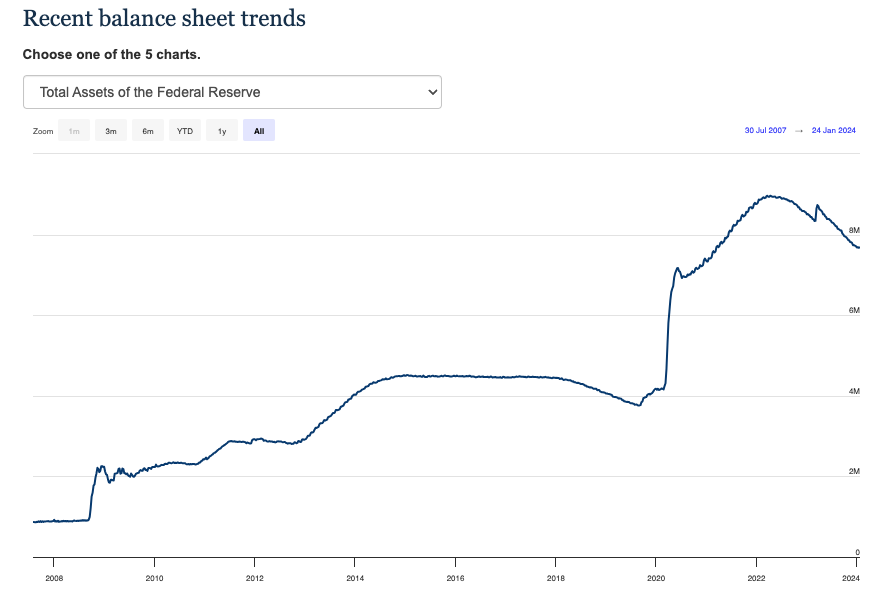

The Fed announced a balance sheet reduction plan in March 2022 when it could no longer convince everybody that price inflation was “transitory.” It called for $30 billion in US Treasuries and $17.5 billion in mortgage-backed securities to roll off the balance sheet in June, July, and August of 2022. That totaled $45 billion per month. The Fed said it would increase the pace to $95 billion per month in September 2022, capping the U.S. Treasury roll-off at $60 billion.

It wasn’t exactly an ambitious plan.

If the Fed followed the blueprint, it would take 7.8 years for the Fed to shrink its balance sheet back to pre-pandemic levels.

To date, the Fed has rolled about $1.29 trillion off the balance sheet. This sounds impressive until you realize that the central bank blew up the balance sheet by $4.81 trillion in just two years in response to the pandemic.

And they are already talking about ending quantitative tightening.

Stop and consider what this means. The central bank only wrung a little more than a quarter of the inflation it created during the pandemic out of the economy.

This explains why despite rate hikes and quantitative tightening, financial conditions remain loose in historical terms. As of the week of January 19, the Chicago Fed Financial Conditions Index stood at -0.57. A negative number indicates loose financial conditions.

It has been an unimpressive inflation fight. That’s why I say the pivot by the Fed isn’t victory, it’s surrender. Inflation won. The Fed is throwing in the towel.

Why?

Because everybody knows that this debt-riddled economy can’t keep plugging along without easy money.

Furthermore, the Federal Reserve can’t shrink its balance sheet in a meaningful way.

A BALANCE SHEET HISTORY LESSON

When the economy is bad, the Fed ramps up quantitative easing. It buys bonds on the open market with money created out of thin air. By putting its big fat thumb on the bond market and creating artificial demand, it keeps bond prices higher than they otherwise would be. Conversely, interest rates stay lower. This benefits the U.S. Treasury, allowing it to continue borrowing at lower interest rates.

This is called debt monetization. The Fed literally transforms U.S. government debt into money.

Debt monetization is inflationary. It expands the money supply and ultimately pushes consumer prices higher than they would be. In practice, Americans pay an inflation tax to help sustain the debt.

When times are good, the Fed should theoretically pull that liquidity out of the economy, but in practice, the central bank is very slow to shrink the balance sheet. Why? Because once it injects trillions in liquidity into the economy, it can’t get it out without popping the bubbles it blew up and driving the economy into a recession.

We witnessed this song and dance after the 2008 financial crisis.

In the early days of the Great Recession, then-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke assured Congress that he was not monetizing debt. Bernanke claimed the difference between debt monetization and the Fed’s plan was it was not providing a permanent source of financing. He insisted the bonds would only remain on the Fed’s balance sheet for a short time and assured Congress that once the crisis was over, the Fed would sell the bonds it bought during the emergency.

That never happened.

Bernanke ran three rounds of quantitative easing, pushing the balance sheet from $8.98 billion before the financial crisis to just over $4.5 trillion by December 2014.

The central bank tried to unwind its balance sheet in 2018. The FOMC said balance sheet reduction was on “auto-pilot?”

It didn’t last long.

The Fed reversed course after the stock market crashed and the economy got wobbly in the fall of 2018. At its low, the balance sheet fell just below $3.76 trillion. It wasn’t even able to shed $1 trillion of the Great Recession monetary stimulus.

So much for Bernanke’s promise.

Some will claim the Fed had no choice but to reverse balance sheet reduction because of the pandemic, but this is historical revisionism. In fact, the Fed returned to quantitative easing before the coronavirus. But in October 2019, the balance sheet was back above $4 trillion. This was four months before the pandemic shutdowns.

The central bank doubled down on QE during the pandemic and today it’s still nearly double what it was after the Great Recession.

It’s clear that the balance sheet is destined to grow into perpetuity. When the next crisis blows up (and it’s coming sooner rather than later), the Fed will almost certainly pump the balance sheet up yet again.

The ugly reality is the economy depends on inflation. It is built on inflation. Without it, the entire house of cards collapses.

And that’s exactly why the Federal Reserve is already talking about rate cuts and an end to balance sheet reduction.

Keep in mind that an end to quantitative tightening means a default return to quantitative easing. In order to maintain the balance sheet at a given level, the Fed has to resume buying bonds on the open market to replace bonds as they mature. This is what the Treasury needs. It depends on the Fed eating up some of that supply.

This is why you can never expect the Fed to win an inflation fight.

Since the Fed can’t ever wring the liquidity out of the economy in the good times, the inflation never goes away. And with the next crisis, the central bank piles more inflation on top of what was already there.

The trajectory of the balance sheet reveals the ugly truth. The Federal Reserve can’t whip price inflation. And it’s not even trying.

*********