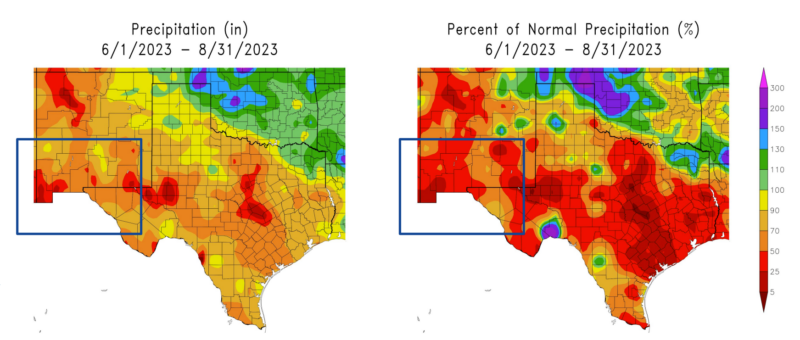

A recent drought information statement from the National Weather Service shows that far west Texas and southern New Mexico are in pretty bad shape. After the hottest summer in history, annual rainfall totals for the area are less than half of what they should be. Even worse, these conditions are not expected to improve going into the fall.

“The majority of the region has seen less than 50% of normal rainfall this summer.” the statement says. “Combined below normal rainfall, above normal temperatures, and breezy conditions result in favorable environment for drought persistence.”

Image from the National Weather Service, Public Domain.

What It Was Like Living Through This

Before I get into the rest of the data the National Weather Service provided, let’s talk about what it was like living through these conditions. If I had to use one word to describe them, it would be “hell.”

Through June and July, I had several big yard projects that we needed to complete if I wanted to be able to travel for work more. For one, I needed to build a better fence to contain dogs during trips. This required not only post-hole digging, but also trenching and moving large bricks to make digging out impossible. Next, I needed to work on building a trailer to carry all of our “glamping” gear, an ongoing project.

But, extreme daytime temperatures made it unsafe to do much of this work in the daylight, so we had to work on all of this after the sun went down. Even then, there were a number of nights where temperatures didn’t drop below 90 degrees (F). So, despite night work, it was still physically exhausting and generally awful work. For louder parts of the trailer project, I had to drive out into the desert to BLM land where it wouldn’t bother the neighbors.

Once we had the trailer ready to go for a basic trip, we took it to one of the highest campgrounds in the area to find cooler air. But, when we went, we encountered an unexpected thermal inversion, making for temperatures that were still too hot to live with without air conditioning, even at 10,000 feet. We managed to get through the trip and get products reviewed thanks to part-time air conditioning powered by solar, but we were thoroughly beat when we went home to the desert instead of feeling refreshed.

Another thing that really sucked about this heat was the cost. Running air conditioning for a small house that we feel a little cramped in ended up costing us $465 for the month of July. This was up from a peak bill of $415 last year, which was also unusually hot.

Having grown up in and around El Paso, it’s obvious that this isn’t just some fluke year or some sort of cyclical record heat. As a kid, daytime temperatures weren’t over 100 degrees (F) for almost the whole summer. That was a thing that mostly happened during the tail end of June. Having a summer with almost no rain also contrasts sharply with my childhood, as we used to get monsoon storms almost every day in July and most of August back then.

Looking back, things have steadily gotten hotter and drier since I was a kid, and this was just the worst yet. Given how cripplingly bad this summer was, I’m seriously considering leaving the area for someplace else.

Short-Term Impacts

This insane dry and hot weather is causing a lot of problems in the desert, both for the people and wildlife living within it.

People who don’t believe something long-term terrible is happening would point to the fact that the Elephant Butte Reservoir is fuller than last year, but that’s mostly a function of Colorado snowpack. A record winter of snow hit much of the western US, and that snowmelt goes into the rivers, including the Rio Grande. So, no, that’s not proof that climate change is a hoax or anything, especially after years of dwindling reservoir water.

For river systems that originate in the region, the outlook is far bleaker. For both the Gila and Mimbres rivers, water flows are far below normal after the mountains they come from dried out prematurely. Grasslands in lower to mid elevations, piñon/juniper highlands, and higher elevation forests are all pretty dry right now, so the risk of fire at all elevations is exceptionally high. The Weather Service says that the risk of dry lightning fires is going to extend well into what should be the fall.

Even worse, the fall isn’t expected to cool down like it usually does. Record highs keep coming back, with recent lowland temperatures spiking above 100 degrees again, in September. So, the situation won’t get better after the region missed out on half of its rainfall.

This seems likely to create fire risks for the whole region all the way until next monsoon season, so we could be in for a rough spring fire season unless there are some significant above-normal winter rains and snows.

Long-Term Impacts

I’m not going to say that the whole region is becoming uninhabitable, because clearly people can survive in what El Paso and surrounding regions got this year. After all, they do this all the time in Phoenix, right?

But, it’s important to keep in mind that this isn’t Phoenix. Wildlife and people have been adapting to 110-120 degree summer weather in that area for a long, long time. Refrigerated air conditioning is the norm in that part of Arizona, and everything from car color to business hours to the lack of Daylight Savings Time all show that people can adapt.

People in El Paso just aren’t ready for this. Many houses have much weaker evaporative air conditioning units (aka “swamp coolers”) that can only lower the temperature by 20-30 degrees at best. As people swap out these water-intensive but electricity-light units out for refrigerated air, power consumption will grow far faster than temperatures. Affording all of this electricity is going to be challenging, as wages are lower in the region than in many other places. Even worse, solar energy that’s abundant in the area could decline in efficiency due to the higher temperatures, making the affordability challenge just that much harder.

Outdoor recreation, and the forests that often serve as a refuge from the heat, will also suffer. Increased fire activity and the inability of forests to regrow could turn areas people used to escape to into barren desert mountain ranges that don’t support snowpack or help rivers get their start.

It’s not the end of the world, but if summers like this keep happening, El Paso is not going to continue to be the place it is today.

I don’t like paywalls. You don’t like paywalls. Who likes paywalls? Here at CleanTechnica, we implemented a limited paywall for a while, but it always felt wrong — and it was always tough to decide what we should put behind there. In theory, your most exclusive and best content goes behind a paywall. But then fewer people read it! We just don’t like paywalls, and so we’ve decided to ditch ours. Unfortunately, the media business is still a tough, cut-throat business with tiny margins. It’s a never-ending Olympic challenge to stay above water or even perhaps — gasp — grow. So …