Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

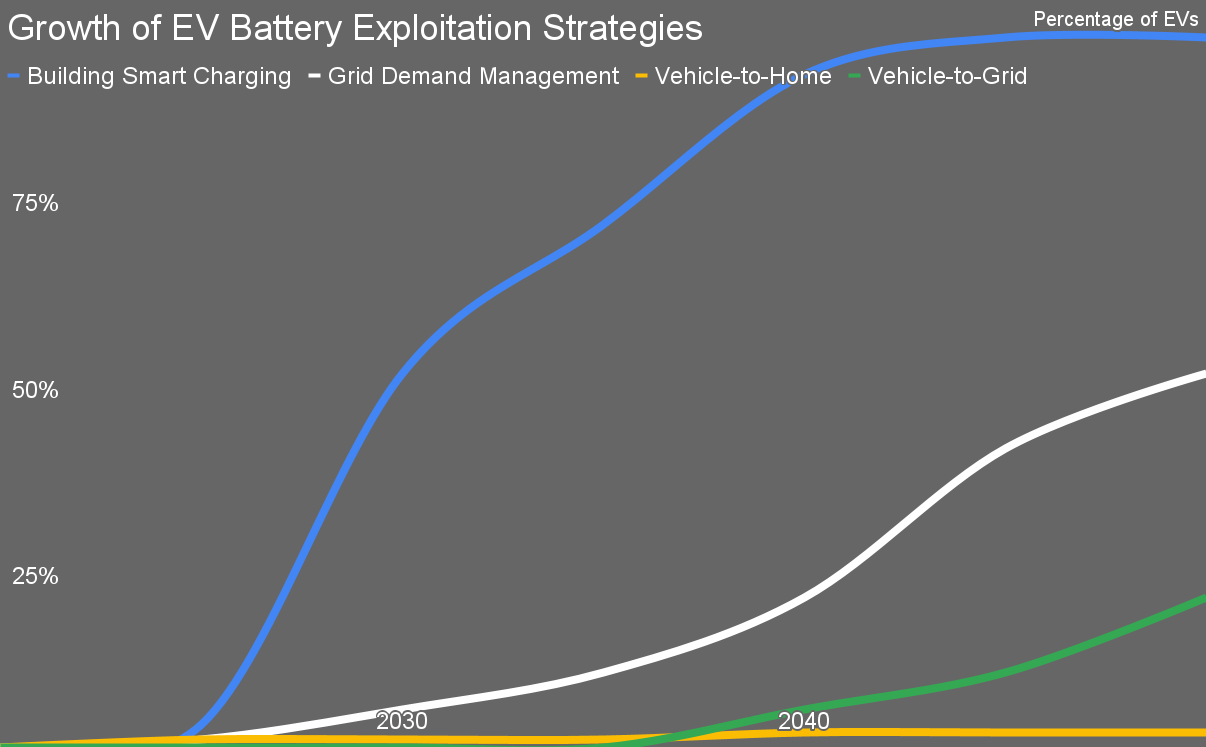

Four years ago, I published one of my first (absurdly arrogant) projection decades into the future, on three pathways for exploiting electric vehicle batteries for grid stability and cost efficiency. Today, it’s worth returning to it and seeing what’s happening in the space.

The trigger for this was a conversation I had with Devashish Paul, CEO and founder of BluWave-ai, and a couple of members of his team. BluWave-ai is commercializing aggregating electric vehicles into a platform that allows turning off their charging when grid demand is high, something electrical utilities value highly. They’re also playing in the fleet space.

As people can see from looking at this chart, which I’ve updated just now to add a fourth pathway, I’m not bullish on what the industry refers to as vehicle-to-grid, where the batteries in electric vehicles are tapped for their stored electricity when demand is high. That model runs into multiple roadblocks, in my opinion, that will limit their utility. Nor am I bullish on vehicle to home.

For vehicle to grid, an obvious challenge is that cars tend to get plugged in when people get home after their commutes, which means that they are part of the demand problem, not part of the demand solution. It’s a timing issue that turns into a psychological issue, as the cars will be lower on electricity in the battery already, and people won’t want them drained any further. People who have five cars in their garage, so don’t have this concern, are also much less likely to bother to sign up to let other people access their batteries. They don’t need the money.

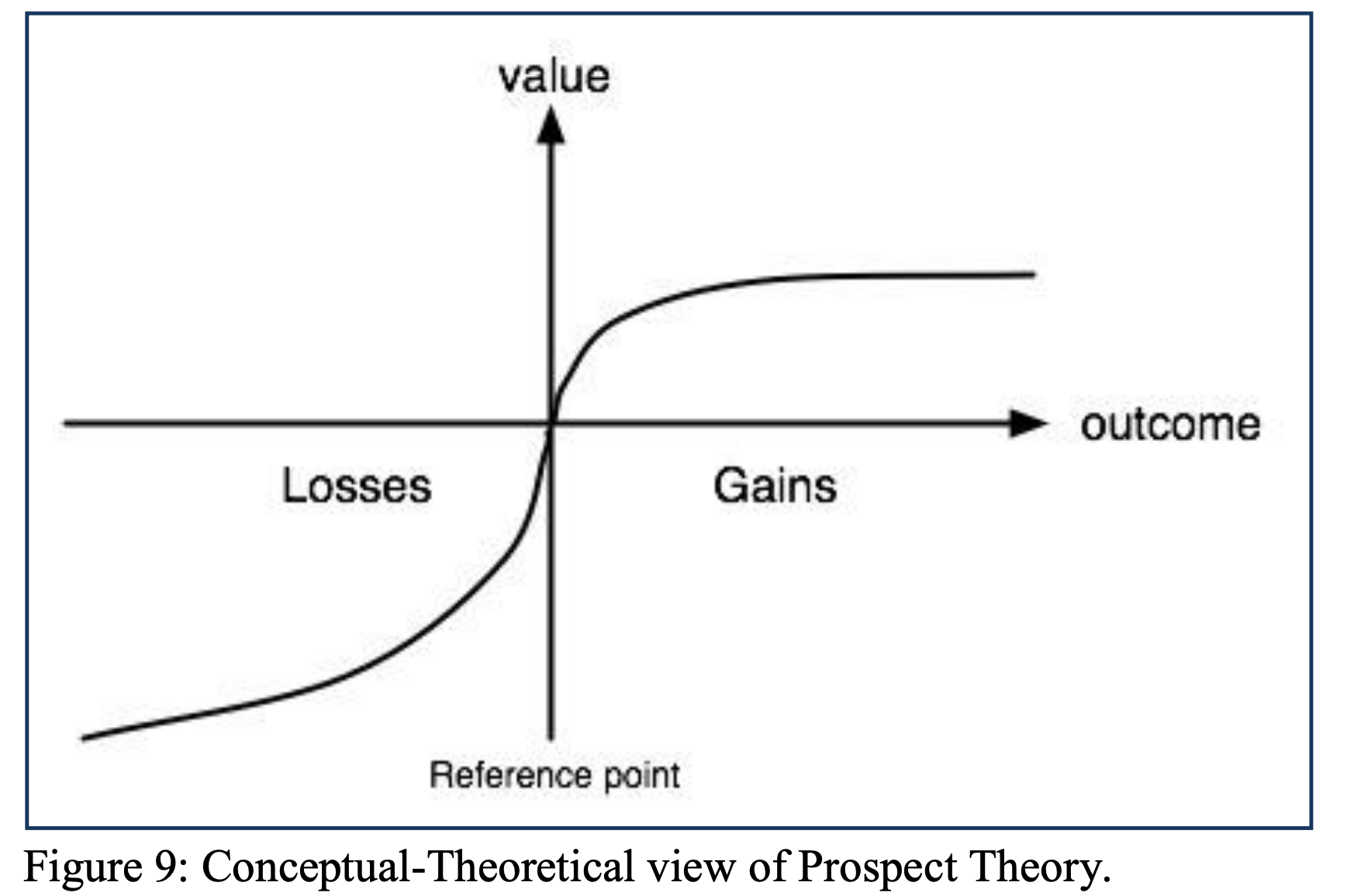

The second is the psychological reality that Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky identified and validated experimentally, prospect theory. Real people, not the Spock robots that economists pretend exist, don’t value potential gains and losses equally unless they train themselves hard to overcome their natural inclinations. Day traders and poker players train themselves into being homo economicus, or some facsimile thereof, but even they are typically only like that when day trading or playing poker.

Real people fear loss a lot more than they value gain. If they have something, they value it more highly than they would pay for it. How this plays out is that if they have charge in their electric vehicle batteries, they won’t want to give it up without high compensation. They’ll also fear, mostly irrationally, degrading their batteries by having them cycled more. That’s a problem for getting people to sign up for it. They aren’t going to sign up out of the goodness of their hearts, they won’t go looking for the service because it’s attractive, and so getting electric vehicles to sign up can be tough.

The last reason is that grids don’t want the amount of electricity in an electric vehicle battery, they want the electricity in 10,000 electric vehicle batteries. That means someone has to build the aggregating system and make it available to the utilities. Most startups are attracting pretty minuscule funding. One managed to get $10.1 million.

The one that makes the most sense in this space is Synop, which leverages electric school bus batteries with a fleet solution. That makes more sense, as school buses have limited duty cycles, are off the road prior to peak demand period, and are run by firms that use spreadsheets, not house husbands who go with their gut feel.

Vehicle to home is an even more limited market, which will surprise a lot of Americans and Australians. The reason is very straightforward: the vast majority of people in the world live in multi-unit residential buildings with shared parking lots and no connection between their parking stall and their cubic meters of residential space. Electricity flowing out of their cars is going to the corporation that runs the building, not to their goldfish tank, Playstation, or wine fridge.

Only people who live in detached homes with driveways can leverage vehicle-to-home technologies, using their vehicles’ battery to keep the lights on should the grid go down. And that’s really its use case at homes, emergency backup power. There’s little economic merit in it. In the USA, there’s this weird compulsion to go off grid that leads people to spend a lot more money for inferior electricity quality in the vain belief that this is better than paying someone else very little money for high quality electricity. In Texas, that’s maximized and their grid reliability is terrible because the grid is run for the profit of corporations, not as a public service. Texans often end up freezing in the dark or paying exorbitant electricity prices, so a pickup truck that can keep the beer cold is a good investment. On average, Texans experienced 273 minutes of grid interruption in 2022, just under five hours.

Australia has a lot of sprawl and an awful lot of ranch homes with big rooftops too, as well as a not terribly reliable grid, averaging about 200 minutes or 3.3 hours of outages a year. They have the rare distinction of having more living space per person on average than the United States, far more than the global average or the averages in other western countries for that matter. Detached homes with driveways are the norm.

For contrast, Germany and Denmark are down around 13 minutes per year per customer of outages.

However, even in US sprawl, 20% of suburban dwellers live in multi-unit residential buildings, so it’s not as if everyone that has to drive a long way to work or grocery shopping can take advantage of this. US suburbanites are about 1% of the world’s population.

The patterns of living many Americans and Australians experience and the ones often represented in media are not nearly as common as they think. That’s another cognitive bias Kahneman and Tversky studied, the availability bias, where things that you can think of easily because you see them regularly are considered to be much more statistically prevalent globally.

Of course, work vehicle to task power is a different beast. Being able to use the comparatively huge battery in a pickup or van instead of a generator at work sites to power tools and task lighting is a great use case, but that only makes sense on small work sites that don’t have electricity of their own. It’s of little use on infrastructure or commercial building construction sites, for example. It’s of use for people maintaining farms with battery powered tools and operating seeding and spraying drones, but even there, as farm equipment electrifies, there will be much bigger batteries available than those in the pickup truck. In some cases, it will be used for car camping as a power source, but a lot of places where you can park your car beside the place you set up your tent come with plugs, and the large majority of westerners don’t camp in any event, and when they do it’s for a day or five a year.

No, the big hitters from my perspective are in the demand management space, getting electric vehicles to stop charging when demand is high. That’s going to come in two flavors, automatic and aggregated.

The automatic one will be pretty much every place where a lot of vehicles park today. That’s fleet depots and maintenance yards, commercial parking lots, office parking lots, and residential building parking lots. They are rolling out charging at a lot of stalls and that will just continue as more and more electric vehicles arrive. Office buildings are going to offer all their employees charging, malls want their customers to come and spend money, and residents are already voting with their feet when they look at buildings to move into, choosing ones that have electric vehicle charging over otherwise equal ones that don’t.

Why will it be automatic? Because the firms that operate the office buildings, malls, condo buildings, and commercial parking lots are paying for the electricity, and there are demand charges. For my condo building in downtown Vancouver, where I coordinated getting electric vehicle charging installed a couple of years ago, a quarter of our electrical bill is demand charges. When the building draws more than a set amount of kW, the corporation that owns and operates the building, the strata, pays $5.35 for every kW of power over the cap the building draws. Condos in the building are metered separately, but once again the parking stalls aren’t metered with the apartment, but go to the building.

As a result, all of the firms which operate bigger buildings already have power management systems that try to avoid those demand charges if possible. As a bunch of electric vehicles add to the load, smart charging systems will draw less at peak demand periods to avoid them as a pretty standard feature. If the vehicle is plugged in at work during the day, charging can run steadily during the sunny midday, but as quitting time rolls up, charging will diminish to a trickle.

Utilities don’t have to do a thing to make this occur except put sufficient demand charges on commercial electricity rates. The market will take care of all the rest automatically, with charging vendors highlighting the quality of their energy management solutions and promising to avoid big demand payments.

That’s every parking lot, mall, hospital, office building, condo building, and apartment building in the world. That’s why that’s the biggest percentage of penetration.

But then there’s the next level. Utilities already pay big electricity consumers like steel mills and paper mills to shut down equipment in 5 MW and 10 MW chunks when demand is high. They run procurement auctions to get organizations to sign up for this in return for often significant compensation. They integrate their electricity management systems into the operations of the steel mills and the like, and have the authority negotiated in the contracts to turn off a big demand draw from their ancient green screen systems. A SCADA-command goes out, the big point source demand shuts down, the steel mill gets whatever notice they negotiated for.

Four years ago, I posited that someone would aggregate the electric vehicles into large blocks for demand management, bid on the demand management auctions, and integrate to the utilities’ electricity management system. I thought it would be an organization like ChargePoint, with its 67,946 charging ports across 37,719 charging stations in the United States.

And when I checked just now, sure enough, ChargePoint is indeed offering utilities demand aggregation services, as well as doing the same in the buildings it’s installing its products in. However, while it’s the biggest provider of charging services, it’s far from the only one. And its primary customers, electric vehicle drivers, are paying it for charging, so there’s a limit to what it can do without annoying them. There’s an interesting strategic dynamic between revenue streams and customer loyalty at play there.

But there are other ways to aggregate demand management without dealing with the chargers at all. Telematics combines telecommunications and data analytics to monitor and manage vehicles in real-time. It provides insights into location, battery health, charging status, and driver behavior, making it an essential tool for fleet operators and EV users. The technology supports route optimization, energy management, and predictive maintenance, helping to reduce costs and improve efficiency. Telematics is widely used in electric vehicle fleets, car-sharing services, and subscription models, offering a practical solution for managing the growing complexity of connected and electrified transportation. Telematics firms provide access to electric vehicles which are registered with them, either as part of vendor telematics like Tesla’s which include over-the-air updates or as third party telematics which offer other solutions. If you have an app that provides any information about your vehicle or controls it in any way, that’s going through a telematics back end.

Telematics solutions can tell if an electric vehicle is charging and have the ability to send a command to turn charging on and off. Most of the vendors aren’t offering that, as it’s secondary and their customers aren’t utilities, but the capability is there to be exploited.

Enter BluWave-ai. Based in Ottawa, they had the insight a few years ago that they could aggregate electric cars, reward drivers in some way without taking electricity out of their batteries, avoiding that cognitive trap, and bundle a big chunk of demand, about a MW per thousand cars, to offer to utilities. They’ve proven the solution, have hundreds of drivers signed up in the Ottawa area, and have run about 100 demand actions at the local utility’s request. Now they are expanding with a driver acquisition push in Ontario and Prince Edward Island. Drivers signed up with them this month will be entered in a series of draws at the end of the month with a total of $5,000 CAD in prizes.

It’s an interesting chicken and egg scenario. Utilities won’t be interested unless a lot of drivers are signed up, and it’s hard to reward drivers fiscally for deferring charging unless utilities are signed up to pay for it. BluWave has to aggregate a bunch of drivers with upfront investment in order to make an attractive offer to utilities, so that’s the expansion stage it’s in.

Once a driver signs up, it’s pretty automatic. Register their car via BluWave’s app and BluWave’s systems can see state of charge, location, and charging status. If a demand management request comes from the utility, BluWave can turn off enough cars’ charging to provide a demand reduction. Of course, the users have to agree to this, so right now the model is that every user’s app notifies them of the request and gives them the option of opting out. If they don’t opt out, charging is turned off for a while. Because BluWave intelligently designed the customer interaction as an opt out, they have very few drivers opt out at requests, well under 10% on average.

That’s part of the stochastic data they have to deal with when offering a block of MW to a utility, of course. They are using statistical models about vehicle type, state of charge history, and the like to figure out how much power they can turn off, and it’s moderately imprecise. They are working with utilities to figure that out and reconcile billing, but electric vehicle demand management is only one of the demand and supply levers utilities have, it’s just a new one.

As I discussed earlier today with the BluWave team, the notifications are potentially annoying in the winter and summer when demand management requests will be coming most evenings and daily notifications will be happening as a result. That’s going to require some management and thinking. It’s also more seasonal revenue for BluWave as a result, and architecting how much to flow through to car owners is going to be a source of ongoing discussion and refinement.

Another of BluWave’s products does fleet energy management, the commercial demand charge management solution that I believe is going to be a very big part of the solution.

As I said to the team, they are working in a specific part of the emerging energy economy which is important and growing fast, and after poking at the solution, they are doing all the right things. No surprise they are looking for their next funding round. The cleantech SPAC pump and dump debacle that’s played out over the last five years, especially in North America, hasn’t helped at all, nor did the global inflation surge in 2022 through 2024 which put a different damper on venture capital funding. With luck, they’ll be one of the thriving firms in a few years. They deserve to be.

If you’re an electric vehicle driver in Ontario or Prince Edward Island, hop over to BluWave and consider signing up.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy