Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Last Updated on: 5th March 2025, 11:13 pm

Hydrogen for energy has been the subject of extravagant claims for decades, and they keep being repeated. When you run into a hydrogen for energy enthusiast and they start saying things that make it seem as if hydrogen for energy is a slam dunk, have a look through this. Some claims are less false than others, but all hydrogen for energy claims are misleading.

Claims That Are Less False

Saying hydrogen is abundant is like saying gold is easy to get—it’s out there, but you have to work hard to extract it.

A misleading claim that’s often brought forward is that hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe.

However, this fact is used to imply that hydrogen is readily available as an energy source.

While hydrogen is abundant, it rarely exists in its pure form on Earth. Instead, it is typically bound in compounds like water (H₂O) and hydrocarbons, meaning it must be extracted through energy-intensive processes such as electrolysis or steam methane reforming.

Being abundant doesn’t make hydrogen accessible.

Hydrogen as a fuel is like building a house on sand—unstable, costly, and hard to maintain.

A frequent and problematic claim is that hydrogen can be used as a fuel across multiple sectors, including transportation, industry, and power generation. However, this does not mean it is a practical or cost-effective solution.

Hydrogen faces significant technical and economic challenges. Its low energy density requires high-pressure storage or cryogenic cooling, adding complexity and cost. Transporting hydrogen is also difficult, whether as a compressed gas, liquid, or carrier like ammonia. Additionally, most hydrogen today is produced from fossil fuels, making it a high-emission energy source unless produced using renewables.

While hydrogen might have potential in niche applications where direct electrification is impractical, it still has to compete with typically more efficient, effective and lower cost alternatives like biofuels.

Yes, hydrogen can be a fuel, but it’s an expensive and inefficient one.

Electrolysis for energy-carrying hydrogen is like driving in circles when the straight path is just ahead—inefficient and wasteful.

Another claim that’s overstated is that we can make hydrogen cleanly from electrolysis. Hydrogen can indeed be produced using renewable electricity through electrolysis, a process that splits water into hydrogen and oxygen. This method, known as green hydrogen production, avoids direct carbon emissions.

However, because direct electrification use cases like electric vehicles and heat pumps are three to six times more efficient, whatever full lifecycle carbon is embodied in the electricity is multiplied by three to six times as well. It will always be lower greenhouse gas emissions to use electricity directly.

This is framing rhetoric, where the information is selectively presented in a way that makes the claim more appealing—by focusing on the absence of direct emissions in the electrolysis process, but not addressing the indirect emissions or inefficiencies that undermine its potential as a clean energy solution.

Electrolysis works, but it’s a higher emissions detour for clean energy.

Using hydrogen for energy is like buying a fancy blender when a knife gets the job done quicker and cheaper.

Hydrogen advocates often state part of the picture, not the whole picture, when they say that hydrogen fuel cells convert hydrogen into electricity with efficiencies of 50-60%, higher than internal combustion engines.

However, this efficiency figure only tells part of the story. Producing hydrogen, compressing or liquefying it, transporting it, and then converting it back to electricity results in major energy losses—often exceeding 70% over the full energy chain. In contrast, using electricity directly in batteries or the grid retains 80-90% of the original energy, making it a far more efficient choice.

This argument is an example of cherry-picking or selective evidence, where only specific parts of the story are presented to support a particular viewpoint while conveniently ignoring other relevant details.

Why settle for 50% efficiency in a fuel cell when batteries deliver 90%?

Wasting cheap electricity on hydrogen is like using a gold spoon to stir a cup of diner coffee—it’s inefficient and over-the-top.

Hydrogen proponents often make the misleading claim that since there will be surpluses of electricity when both the sun is shining and the wind is blowing, hydrogen can be made cheaply during those periods.

Electrolyzers require high utilization rates to be cost-effective, but excess renewable electricity is intermittent by nature. Running electrolyzers only during surplus periods leads to poor utilization, making hydrogen production expensive. Meanwhile, there will be competition for cheap electricity, and most of it will be more efficient and economically viable than throwing away 70% of the energy in hydrogen for energy use cases.

This is an example of the hasty generalization fallacy. The claim assumes that because there might be surpluses of electricity when renewable sources like solar and wind are generating excess power, hydrogen can be made cheaply during those times.

Why waste cheap surplus electricity making costly hydrogen?

Hydrogen burns clean, but it’s like sweeping the dirt under the rug—ignores NOₓ emissions and leaks.

Hydrogen burns clean, but it’s like sweeping the dirt under the rug—ignores NOₓ emissions and leaks.

Hydrogen proponents often claim that hydrogen doesn’t emit carbon dioxide when burned or used in fuel cells, however, this claim ignores other serious climate concerns.

Hydrogen itself is a potent indirect greenhouse gas as it extends the atmospheric lifetime of methane, amplifying climate change. Recent research shows that hydrogen has a global warming potential at 100 years (GWP100) of 12 and a GWP20 of 37, meaning it is many times more impactful than CO₂ in the short and long term. Hydrogen is highly prone to leakage due to its small molecular size, 1% or more per point of handling in value chains, hence 5% to 10% for hydrogen for energy use cases.

Hydrogen combustion produces significant amounts of nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), harmful air pollutants that contribute to smog and respiratory diseases as well as being a potent and long-lasting greenhouse gas. Controlling NOₓ emissions from hydrogen flames requires additional mitigation measures, increasing costs and complexity.

This argument exposes the fallacy of incomplete comparison (or cherry-picking), where hydrogen proponents highlight only one advantage—no CO₂ emissions—while ignoring other significant environmental drawbacks, such as high GWP leakage and NOₓ emissions. By focusing solely on CO₂, they create a misleadingly favorable impression of hydrogen’s climate impact.

No CO₂? Sure. But what about high GWP NOₓ and hydrogen leaks?

Hydrogen for energy is like trying to use a wrench for a screwdriver job—inefficient and costly.

Another misleading claim is that hydrogen is widely used in industry today, so it’s suitable as a broad energy carrier.

The hydrogen used in industry today is almost entirely gray hydrogen, produced from fossil fuels like natural gas via steam methane reforming (SMR). This process emits significant amounts of CO₂—in the same range as all of aviation globally.

Additionally, industrial hydrogen is used in processes that require hydrogen specifically as a feedstock, not as a general energy source.

Expanding its use into transport, heating, or power generation would require an entirely new hydrogen economy, complete with expensive storage, transport, and distribution networks—all while competing with more efficient electrification alternatives.

This claim is an example of the equivocation fallacy, where the meaning of “hydrogen use” is shifted to imply a broader applicability than actually exists.

Hydrogen is used in industry—but not for clean energy.

Transporting hydrogen through old pipes is like trying to squeeze a basketball through a garden hose—requires a lot of adjustments.

Transporting hydrogen through old pipes is like trying to squeeze a basketball through a garden hose—requires a lot of adjustments.

Hydrogen proponents like to make the simplistic and misleading claim that we’ll reuse existing gas pipelines for hydrogen.

Transporting hydrogen through existing pipelines requires extensive upgrades. Linings must be replaced to prevent hydrogen embrittlement, as hydrogen can damage traditional pipeline materials. Electronics need to be upgraded for accurate monitoring and control, as hydrogen’s flow characteristics differ from natural gas and hydrogen reacts badly with electronics that natural gas doesn’t react to, damaging them unless they are designed for hydrogen. Compressor replacements are necessary to handle the higher pressure required for hydrogen transport as well as the smaller molecules. These modifications make hydrogen pipeline transport complex and costly.

The logical fallacy in the original claim is hasty generalization. The claim suggests that because hydrogen can be transported via pipelines with modifications, it is an easy and scalable solution.

Transporting hydrogen via existing pipelines requires far more than just tweaks.

Cryogenic hydrogen is like using a leaky thermos—more energy is lost in the process than is saved.

Hydrogen advocates make the misleading claim that liquifying hydrogen for transportation solves the problems of its lack of density.

While it is true that hydrogen can be liquefied, the process is far from simple or energy-efficient. Liquefying hydrogen requires cooling it to a temperature of -253°C, a process that consumes a full third of the energy embodied in the hydrogen. Furthermore, the infrastructure required for cryogenic storage and transport is complex, costly, and prone to energy losses during transfer and storage.

The logical fallacy in the original claim is oversimplification. It presents liquefied hydrogen as a straightforward solution for storage and transport, ignoring the substantial energy demands and infrastructure challenges involved.

Liquefying hydrogen makes transport easier, but wastes a lot of energy.

Ammonia’s hydrogen promise is like trying to use a funnel as a soup bowl—a lot of it will end up on your clothes.

Ammonia’s hydrogen promise is like trying to use a funnel as a soup bowl—a lot of it will end up on your clothes.

While ammonia (NH₃) is often touted as a potential hydrogen carrier, the reality is far less promising.

It is true that ammonia can be used to transport hydrogen due to its high hydrogen density and existing infrastructure. However, the process of cracking ammonia back into hydrogen—a necessary step for its use in fuel cells or coal plants—remains highly costly and inefficient. This inefficiency makes ammonia far from a viable solution for large-scale hydrogen storage and transportation.

This claim falls into the false dilemma fallacy, where proponents present ammonia as a straightforward, low-cost hydrogen solution without addressing the significant technological and economic barriers.

Ammonia is not the ultimate hydrogen carrier.

Claims That Are Mostly False & Misleading

Hydrogen’s zero-emissions claim is like calling a sieve full—emissions still leak through at every stage.

The claim that hydrogen is a zero-emissions energy source is misleading.

While it’s true that hydrogen itself produces no CO₂ when used in fuel cells, the majority of hydrogen produced today comes from fossil fuels, specifically through processes like steam methane reforming (SMR). These methods, which are responsible for the vast majority of global hydrogen production, release significant carbon emissions. Only a small fraction of hydrogen is produced using low-carbon methods, like electrolysis powered by renewable energy.

Additionally, hydrogen’s global warming potential further complicates its emissions profile. Over a 20-year period, hydrogen has a GWP of 37, and over 100 years, its GWP is 12. This means that even small leaks—empirically over 1% at each step in production, storage, and transportation—significantly increase its climate impact.

This claim is an example of the cherry-picking fallacy, where only the positive aspects (zero emissions during use) are highlighted while conveniently ignoring the environmental cost of its production.

Hydrogen is not zero-emissions.

Green hydrogen is like trying to power a rocket with firecrackers—high cost and inefficiency make it a tough launch.

Green hydrogen is like trying to power a rocket with firecrackers—high cost and inefficiency make it a tough launch.

While green hydrogen is often asserted to be the future of energy, this claim overlooks significant challenges.

Green hydrogen, produced via electrolysis powered by renewable energy, faces major hurdles as an energy carrier, including high production costs, the need for extensive infrastructure, and energy losses during conversion and transportation.

Moreover, more direct forms of electrification, such as battery electric vehicles and electric heating, offer higher efficiency and lower total cost of ownership compared to hydrogen solutions. Direct electrification avoids the significant energy losses inherent in hydrogen production, storage, and conversion processes. This makes it a more efficient and economically viable option for many applications, particularly when powered by renewable electricity, offering a more immediate path toward reducing emissions.

This claim exemplifies the appeal to future possibilities fallacy, where an idealized vision of the future is presented without addressing the current technological, economic, and logistical barriers.

Green hydrogen is not the future of energy.

Hydrogen may weigh less, but storing it is like trying to squeeze a watermelon into a soda can.

While hydrogen is often touted for its high energy density by weight, this is misleading.

Hydrogen’s energy density by weight is indeed high compared to many other fuels, but when it comes to practical energy storage and transportation, hydrogen’s low energy density by volume presents significant challenges. Hydrogen requires either compression equivalent to 3.5 to 7 kilometers under the surface of the ocean, liquefaction to 18° above the background temperature of deep space to store and transport, or both, all of which consume a substantial amount of energy. This significantly reduces its effective energy density and makes it less efficient than other fuels, such as liquid hydrocarbons or even batteries, when considering real-world applications.

This claim falls into the misleading statistics fallacy, where hydrogen’s energy density is presented in an overly simplistic way without considering the full context of how it must be stored and used.

Hydrogen is not as energy dense as it seems. Yes by mass, but not by volume.

Hydrogen for heating is like using a sledgehammer to hang a picture—heat pumps are the precision tool for the job.

Hydrogen for heating is like using a sledgehammer to hang a picture—heat pumps are the precision tool for the job.

The misleading gas industry claim that hydrogen will replace natural gas in heating buildings and water is highly unlikely.

While hydrogen can technically be used for heating, it is significantly less energy-dense by volume than natural gas, meaning more hydrogen is needed to produce the same amount of heat. Additionally, hydrogen’s high cost and the inefficiencies of producing, storing, and transporting it make it a much more expensive option compared to electrified heat pumps, which are more efficient and cheaper to operate in most scenarios. Jan Rosenow of RAP has 54 independent studies in his meta-analysis finding no place for hydrogen commercial or residential heating compared to heat pumps as a result.

This argument falls into the False Hope fallacy, presenting hydrogen as a clear substitute for natural gas without considering the practical limitations in efficiency, cost, and energy density.

Heat pumps not hydrogen for heating.

Shifting from fossil hydrogen is like turning off a leaky tap—it’s the first step toward stopping the flow of emissions.

As a hard to abate sector, there are often misleading claims made about hydrogen as an energy replacement in heavy industry.

While hydrogen may be a key option for decarbonizing specific sectors like steelmaking (through hydrogen direct reduction) and certain chemical processes, it’s not the universal solution many claim it to be. Electrification, particularly in industries like cement and aluminum production, often proves to be a more efficient and cost-effective alternative. The push for hydrogen in heavy industry overlooks the potential of electrification technologies, which are becoming increasingly viable with renewable energy sources.

Each year, approximately 100 million tons of black or gray hydrogen, which is produced from fossil fuels like natural gas and coal, are used globally. This hydrogen production method generates significant carbon emissions, contributing to climate change. To meet global decarbonization goals, these fossil-based hydrogen sources must be replaced with low-carbon alternatives, such as green hydrogen produced via electrolysis powered by renewable energy or alternative processes that don’t use hydrogen at all.

This claim falls into the overgeneralization fallacy, where hydrogen is presented as a one-size-fits-all solution for decarbonizing heavy industry without considering that in many cases, electrification may offer a better pathway.

Decarbonize hydrogen feedstocks for industry, not hydrogen for energy.

Hydrogen in transportation is like using a horse when cars are available—EVs and biofuels are just more efficient.

Hydrogen in transportation is like using a horse when cars are available—EVs and biofuels are just more efficient.

The false claim that hydrogen-powered vehicles will dominate the transportation sector ignores the significant efficiency advantage of battery electric vehicles and biofuels.

For passenger cars, EVs are far more efficient and cost-effective, making hydrogen an unlikely contender for widespread adoption. Hydrogen buses are vastly outnumbered by battery electric buses and will continue to be, ditto hydrogen trucks. All ground transportation will be electrified, as will all shorter sea and air journeys.

And hydrogen by itself isn’t a good maritime or aviation fuel. It’s inefficient, ineffective and expensive systemically. It has to compete with biofuels for longer haul shipping and flying, and it can’t (nor can synthetic fuels).

The statement is an example of appeal to possibility. It suggests a claim (hydrogen-powered vehicles dominating the transportation sector) without addressing the practical realities or challenges.

Batteries and biofuels will dominate the transportation sector.

Blue hydrogen’s carbon footprint is like a tangled fishing net—full of holes that let emissions slip through.

The fossil fuel industry’s claim that blue hydrogen is a low-carbon fuel is misleading.

While it is produced from natural gas with carbon capture, the overall carbon footprint depends heavily on the leakage rates of both methane, the carbon capture process itself and avoidance of leakage of the resulting hydrogen with its high GWP. Many studies have shown that blue hydrogen projects often have high lifecycle emissions, as methane leaks during extraction, transport, and storage can significantly offset the carbon captured. Additionally, the efficiency of carbon capture technologies is often lower than ideal, leading to less effective reductions in CO₂ emissions.

While blue hydrogen is likely to dominate decarbonization of refineries’ use of hydrogen — the biggest current consumer by far — it’s not a low-carbon, cheap fuel and outside of heavily subsidized governmental programs is not competitive with batteries or grid ties.

This claim falls into the false dichotomy fallacy, presenting blue hydrogen as a clear low-carbon solution without considering the complexities and potential inefficiencies of its lifecycle.

Blue hydrogen is rarely low-carbon.

Claiming hydrogen solves mineral shortages is like using a sledgehammer to fix a leaky faucet—overkill and missing the point.

Claiming hydrogen solves mineral shortages is like using a sledgehammer to fix a leaky faucet—overkill and missing the point.

The false claim that hydrogen is necessary because we don’t have enough minerals for batteries overlooks the reality that the scale of mineral demand for battery production is manageable and can be met through recycling, alternative materials, and advancements in mining technologies.

The assumption that we are facing an imminent shortage of key minerals like lithium and cobalt ignores the ongoing efforts to increase resource efficiency and reduce reliance on these minerals. Additionally, hydrogen itself requires significant resources for production, storage, and distribution, and has specific expensive critical minerals its manufacturing and use depends upon, making it no more immune to resource constraints than batteries.

The logical fallacy in overstating mineral requirements and understating mineral supply and efficiency programs is an example of the straw man fallacy. This fallacy misrepresents the argument by exaggerating the challenges (e.g., an imminent shortage of minerals) to make it easier to dismiss or attack, while ignoring the more nuanced reality, such as ongoing efficiency improvements, recycling, and alternative resource development.

Hydrogen is not necessary because of mineral shortages for batteries.

Hydrogen is the middleman, not the source—it’s like a truck delivering goods that someone else made.

The claim that hydrogen is a renewable energy source is simply false.

Hydrogen is an energy carrier, not a primary energy source. It must be produced using energy from other sources, whether it’s natural gas (in the case of gray hydrogen) or renewable electricity (in the case of green hydrogen). While hydrogen can store and transport energy, it doesn’t generate energy on its own, making it fundamentally different from renewable sources like solar or wind.

This falls into the equivocation fallacy, where “renewable” is incorrectly used to describe hydrogen as if it generates energy like solar or wind, rather than clarifying that hydrogen simply stores and transports energy from another source.

Hydrogen is not a renewable energy source.

Building hydrogen infrastructure is like juggling lit fireworks—technical, costly, and full of safety risks.

Building hydrogen infrastructure is like juggling lit fireworks—technical, costly, and full of safety risks.

The false claim that hydrogen infrastructure is easy to develop overlooks significant practical challenges.

Hydrogen has a very low density, which makes it difficult to store and transport efficiently. Additionally, its high flammability presents safety concerns that require specialized infrastructure, such as high-pressure tanks or cryogenic storage systems, and extensive safety measures. These complexities make developing hydrogen infrastructure both costly and technically demanding.

This falls into the overgeneralization fallacy, where the simplicity of hydrogen’s potential is exaggerated while ignoring the specific and significant challenges involved in safely and effectively building the required infrastructure.

Hydrogen infrastructure is not easy to develop.

Hydrogen in existing engines is like trying to run a race car on coal.

The claim that hydrogen can be used in all existing gas turbines and engines without modification is just wrong.

Hydrogen’s unique properties, such as its small molecular size, can cause embrittlement of metal components, leading to potential failure. Additionally, hydrogen has different combustion characteristics, requiring modifications to ensure safe and efficient operation. These technical adjustments require that existing engines and turbines need significant changes before they can safely use hydrogen. Just because it’s a gas doesn’t mean it can be used as a plug compatible replacement.

This falls into the oversimplification fallacy, which simplifies a complex issue by ignoring the need for modifications and safety measures. It misrepresents the reality of hydrogen’s compatibility with current infrastructure.

Hydrogen cannot be used in existing gas turbines and engines without modification.

Hydrogen leaks are a ticking time bomb—small leaks can make a big mess for the climate.

Hydrogen leaks are a ticking time bomb—small leaks can make a big mess for the climate.

The claim that hydrogen leaks are not a concern overlooks the prevalence and environmental impact of such leaks.

Hydrogen is highly prone to leakage due to its small molecular size, and when it escapes into the atmosphere, it can contribute to indirect climate effects by extending the lifespan of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Even small leaks can have a disproportionate impact on global warming, undermining the potential benefits of hydrogen as a clean energy source.

This claim falls into the minimization fallacy, where the risks and consequences of hydrogen leakage are downplayed or ignored.

Hydrogen leaks are a significant concern.

Saying hydrogen is the cheapest way to decarbonize is like choosing a luxury car when a bicycle gets the job done faster and cheaper.

The false claim that hydrogen is for energy the cheapest way to decarbonize energy systems overlooks the reality that direct electrification is always more cost-effective and efficient.

Electrification, especially when powered by renewable energy sources, is less expensive due to lower operational costs and higher energy efficiency compared to hydrogen production, storage, and conversion processes. Hydrogen has a role in specific sectors as a feedstock, but it’s not the most economical solution for widespread energy decarbonization.

This falls into the false dichotomy fallacy, where hydrogen is presented as the only or best solution for decarbonization.

Hydrogen is not the cheapest way to decarbonize energy systems.

Storing hydrogen is like keeping ice in the desert—it’s expensive and hard to manage.

Storing hydrogen is like keeping ice in the desert—it’s expensive and hard to manage.

The false claim that hydrogen is easy to store for long periods overlooks the significant costs and inefficiencies involved.

Hydrogen storage requires specialized infrastructure such as high-pressure tanks or cryogenic storage, both of which are energy-intensive and expensive. Storing it in proposed underground salt caverns is challenging and leakage rates are problematic. In comparison, alternatives like pumped hydro or batteries are far more efficient and cost-effective for long-term energy storage, making hydrogen a less practical option in most cases.

This falls into the overgeneralization fallacy, where hydrogen’s potential is oversimplified by ignoring the practical challenges and costs of its storage.

Hydrogen is not easy or cheap to store for long periods.

This is intended as an evergreen resource for those interested in quickly cutting and pasting counter arguments into online discussions. If you see a commonly trotted out argument you’d like added, let me know.

It’s an homage to John Cook’s excellent and strongly recommended Cranky Uncle vs Climate Change, available in both book and app form, but with ChatGPT filling in for John’s cartooning talent, and with my interpretation of his debunking guidance filling in for his depth and humor in debunking . If you’ve read this far, go buy Cranky Uncle for all the kids in your life, especially the ones whose parents are the problems at Thanksgiving.

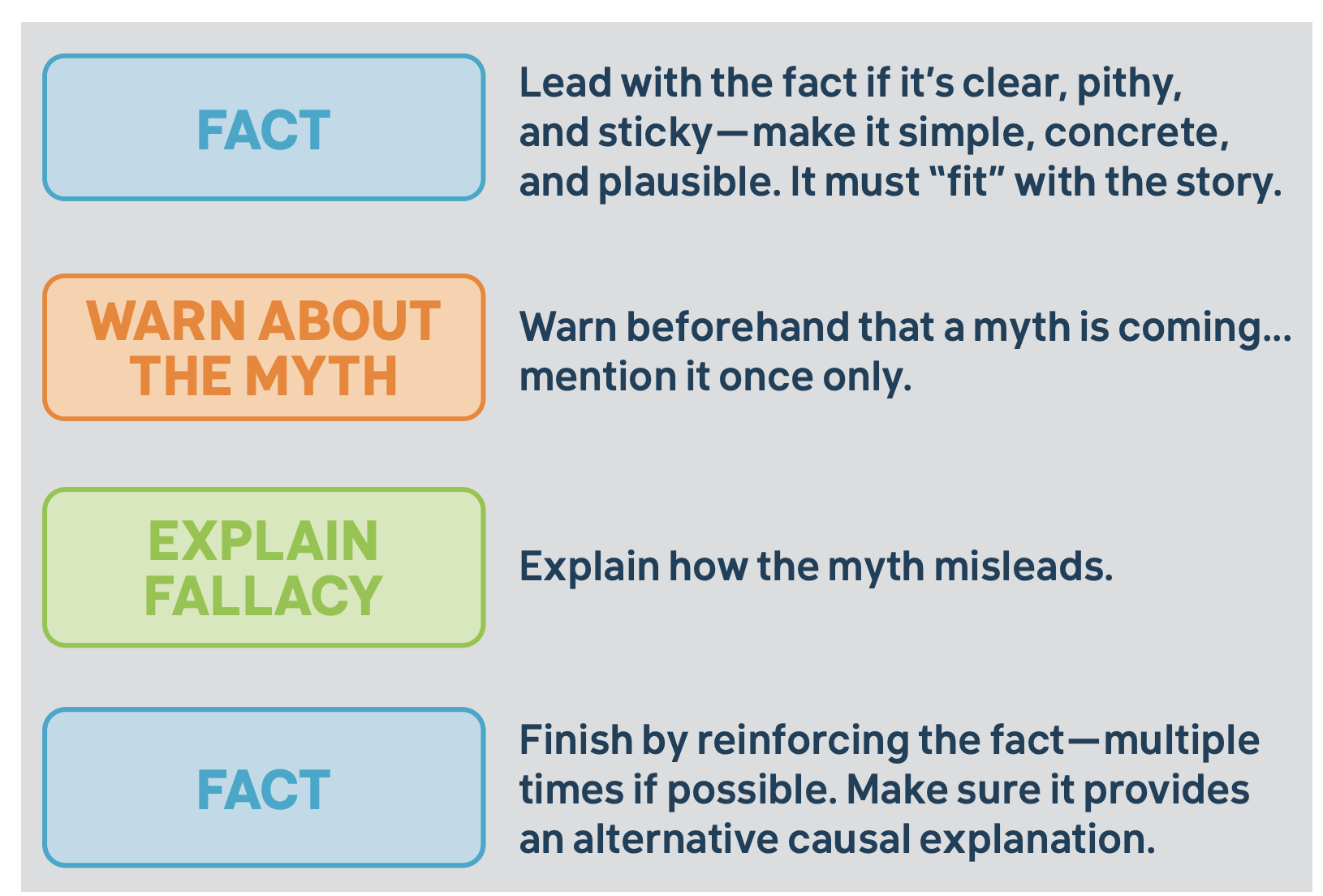

In recent months, I’ve seen a number of posts in social media debunking various things, but doing it without consideration for the most effective process for debunking. I’ve taken to providing this graphic from Stephan Lewandowski and John Cook’s et al’s Debunking Handbook, most recently updated in 2020. If you are engaged in debunking of efforts, I strongly recommend it.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy