Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

The world has gone cuckoo for artificial intelligence. AI is virtually all you hear in the news these days. NVIDIA is worth a gazillion dollars because it manufactures the specialized computer chips that data centers need to make AI possible. Microsoft, Apple, Meta, Amazon, and Google are all rushing headlong into the AI future and building new data centers at a frantic pace. Everyone seems to assume that we are in desperate need of ever increasing amounts of artificial intelligence at a time when human intelligence seems to be in dangerously short supply.

While it is wonderful to know that any high school sophomore can now ask a computer to search every document ever created in the quest for the perfect term paper, there is a component to the quest for ever more computing power that is decidedly sinister. To be specific, the electrical energy needed to power data centers is increasing exponentially. As a result, the hunt is on for more generating capacity. Is that a problem? It very well could be, for a number of reasons.

Data Centers Consume Enormous Amounts Of Electricity

The demand for power to run data centers is a recent phenomenon, one that utility companies did not see coming. As a result, old coal-fired generating stations that were scheduled to be closed are being kept in service to meet that demand for electrons. That means more carbon dioxide and other flue gas pollutants that warm the environment and contribute to poorer health for humans. Those data centers operate 24 hours a day, which makes it more difficult for renewable energy sources to meet their need for electricity consistently. To get the electricity data centers need, utility companies are turning to more gas and nuclear power plants with all the attendant environmental consequences they bring with them. The voracious demand for power to run data centers means there is less electricity available for other business and residential customers.

Data centers have another problem. They create enormous amounts of heat. There are ways to utilize waste heat, but in the majority of cases, all that heat just gets exported to the environment, with predictable consequences. In a recent article, Canary Media said it best: “Big Tech wants massive amounts of energy to fuel their AI ambitions. That could strain utilities, ratepayers, and efforts to decarbonize the grid.”

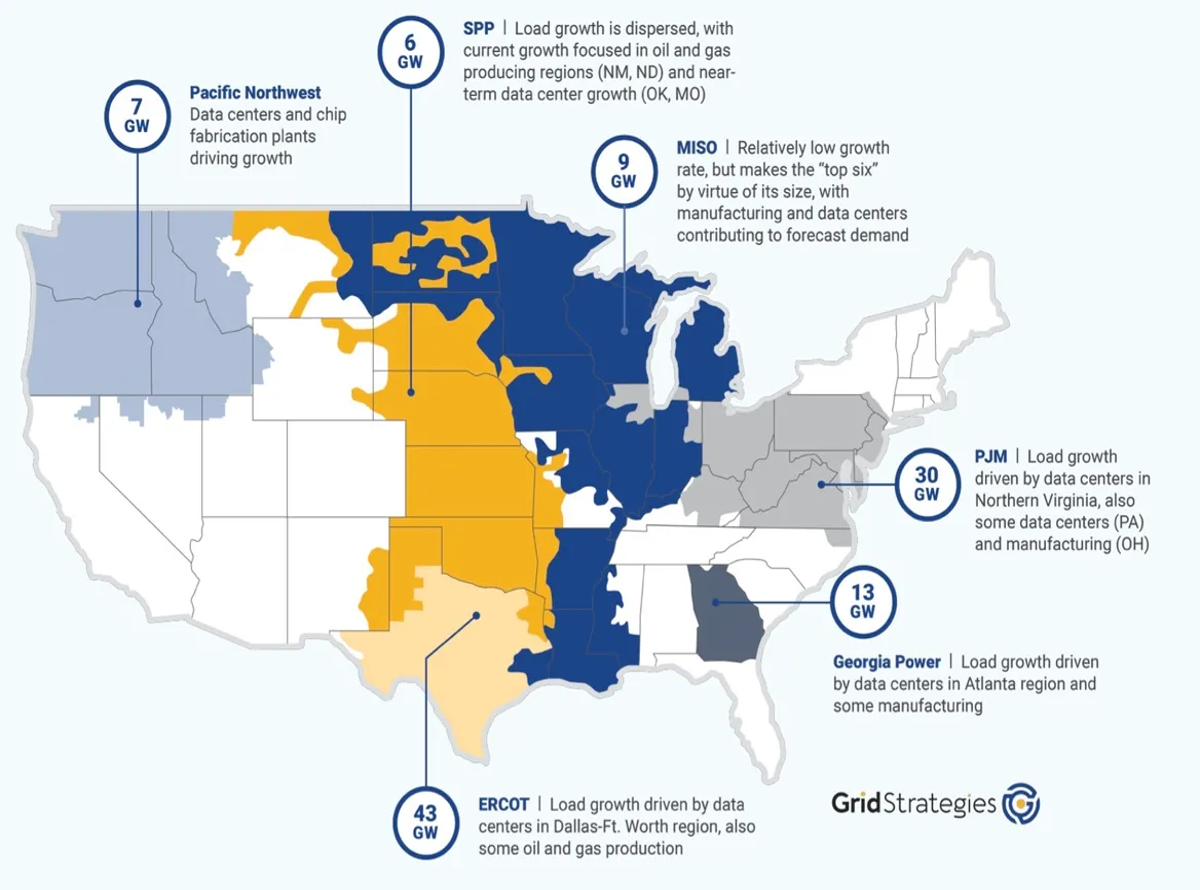

A new report by Grid Strategies suggests the hunger for electricity to operate data canters will accelerate, putting even more strain on these decarbonization goals, as well as on US utilities and the ratepayers who end up paying for the power plants and grid infrastructure needed to support data center growth. Last year, Grid Strategies was one of the first to note that US electricity demand was set to boom beyond expectations over the next five years. Fast forward 12 months, and things have gotten crazy. Federal data shows that five-year electricity demand forecasts have more than tripled in recent years. In 2022, the projection for five years out was 23 gigawatts of new load. By late 2023, that grew to 39 GW. Now, utilities are forecasting 67 GW of new load over the next five years.

But that federal data doesn’t show the whole picture. Taking into account recent updates from Georgia, Texas, Virginia, and other data center hot spots, the country’s five-year load growth forecast has increased almost fivefold in the past two years to nearly 128 GW. The US hasn’t seen that kind of load growth since the 1980s, when the US economy and the power sector were much smaller and climate change wasn’t yet a recognized threat requiring the rapid replacement of fossil fueled thermal generating plants with renewables.

All these factors make the challenge of expanding the US grid and power supply to serve future needs much greater today, said John Wilson, vice president at Grid Strategies. While sectors such as manufacturing, electric vehicles, and electrification of building heating are also adding demand, “data centers have stepped to the forefront,” he said, before adding, “Most of the load growth is occurring in the Dallas-Fort Worth region, in the Northern Virginia region, and in the Atlanta region,” regions where data center developers are seeking gigawatts of power for projects they want to build as quickly as possible.

The Grid Strategies report highlights a year of nonstop data center planning and development, driven largely by big tech firms’ desire to outmuscle one another on generative AI. In Northern Virginia’s “Data Center Alley,” the world’s largest concentration of data centers could nearly quadruple its power demand from about 4 GW today to 15 GW by 2030, according to Aurora Energy Research. That would be equal to half of Virginia’s total electricity load, the Electric Power Research Institute says.

In Texas, forecasts suggest data centers could be responsible for roughly half of new power demand, from 86 GW today to about 150 GW in 2030. In November, Oncor, the utility serving the Dallas–Fort Worth area, reported new requests for connection to its system total 103 GW, with artificial intelligence and data centers making up about 82 GW of that — up from 59 GW for data centers just 5 months ago. Last month, Georgia Power reported its load forecast over the coming decade has tripled from 12 GW last year to 36.5 GW today, with large loads including data centers responsible for 95% — 34.6 GW — of that expected demand.

Who Pays, & How Much?

The idea that data center operators are demanding utilities build new generating capacity while they don’t yet know how much of that extra capacity they will actually need — and therefore pay for — raises some troubling questions. John Wilson of Grid Strategies asks how utilities and regulators can guard against the risk of developing power plants and grid infrastructure to support data centers that might not actually get built. Much of the increase in new data centers plans is being driven by “hyperscalers” like Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft, who want to expand computing capacity for AI services that have yet to prove that they can be profitable. “Let’s say those hyperscalers decide that this business didn’t work out after all and they disappear?” Wilson asks. “You don’t want that cost to be left on the remaining customers. That’s why this issue has become such a hot topic in a lot of jurisdictions.”

His concerns are not idle speculation. Just this week, General Motors pulled the plug on its Cruise automated ride-hailing service after spending $10 billion to get it off the ground since 2016. The company finally decided there was no way to make a profit on its investment and to stop the bleeding. Is there any way to guarantee some of the current AI players won’t come to a similar conclusion in 5 years or so? Most renewable energy installations have a projected 30-year lifespan and most thermal generating stations are expected to operate for 50 years or more. What assurances are data center operators willing to give utility companies that the demand for electricity they are creating won’t end abruptly, leaving other utility customers on the hook financially for decades to come?

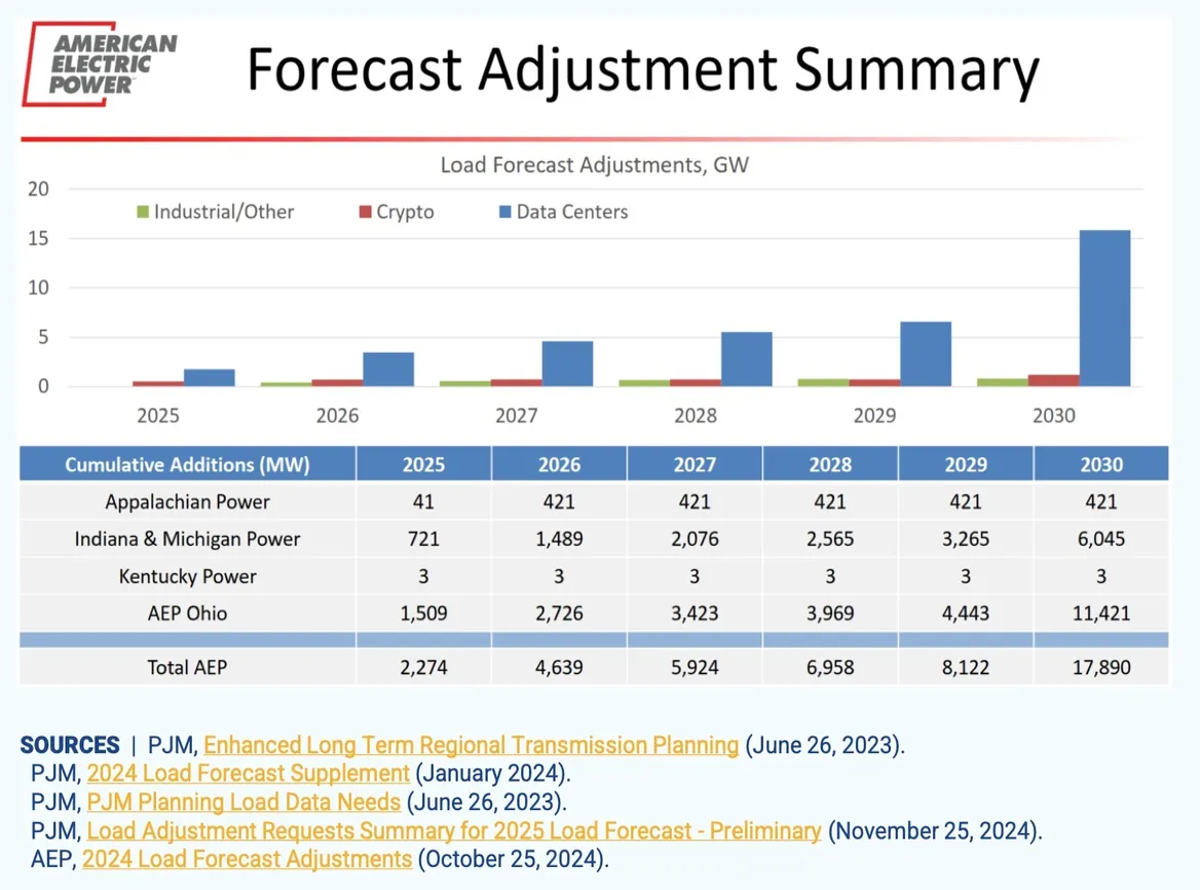

American Electric Power has spent the past year negotiating with regulators and data center companies to approve new rules for data centers seeking to connect in the areas served by its utilities in Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan. A recently approved settlement agreement for AEP-owned Indiana Michigan Power provides one template for “new large loads that are coming onto their system to make certain financial guarantees that they will contribute to the cost of the equipment that is being installed to serve their load,” Wilson said. While data centers are an insignificant portion of today’s load, “they are projecting that it would become over 50 percent of their load in the next 10 years or so.”

Wilson’s second concern is how data centers could affect grid reliability. They can drop off the grid and onto backup power systems at moments when grid power voltage and frequency fluctuate, causing sudden mismatches between electricity supply and demand on grids that must remain in constant balance to run safely. Some data center operations, like cryptocurrency miners, ramp computing use up and down in response to changing electricity market prices at speeds that can disrupt grid operations.

Data Centers & Climate Goals

Another concern is how this spike in electricity demand could hamper efforts to reduce carbon emissions from fossil-fueled power plants. Most of the biggest tech companies driving the data center boom have set aggressive clean energy targets and have played central roles in contracting for renewable energy resources across the country. Yet at the same time, utilities are pointing to the massive new loads coming from data center plans to justify building gigawatts of methane-fired power plants to serve them. There is a major disconnect between what those companies are saying about their emissions reduction goals and the carbon intensity of the electricity they say they will need to power their data centers.

In Virginia, Dominion Energy has a new Integrated Resource Plan which calls for 21 GW of clean energy. But it also includes 5.9 GW of methane-powered generation by 2039. Critics warn that adding that amount of thermal generation will put Virginia’s decarbonization mandates out of reach. In Georgia, which has established no clean energy goals, Georgia Power is arguing with regulators, consumer groups, and data center operators over how much new methane-fired power generation capacity it needs to build to meet its rapidly growing load forecasts.

CleanTechnica readers know the correct answer is none, but we are seeing significant backpedaling on clean energy goals so we can have Google use AI to conduct an internet search. By now everyone should know that AI-enhanced searches use ten times as much electricity as traditional searches. Are we wiling to put our climate at risk to obtain the rather dubious benefits promised by Google Gemini? Some question why Google does not give us the option of bypassing the AI-powered search function. Perhaps they do, but if so they are keeping it a closely guarded secret.

Get Disruptive!

So here’s a thought. We are in the middle of several technology-inspired revolutions — online shopping, cryptocurrency, AI — that break all the rules. Who says the utility grid model developed 100 years ago can’t be disrupted along with all the other disruptions taking place? Why should utility customers be required to subsidize the risks associated with building new generating capacity and transmission lines to quench the insatiable thirst for electricity for data centers? Why can’t Google and others build their own damn generating stations and transmission lines and take on the risks themselves rather than foisting them off on the public?

These are the sorts of questions that get tossed around the employees lounge at CleanTechnica headquarters on a daily basis. They sound like questions our readers might have some interesting answers to. The ball is in your court, dear readers. Have at it!

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy