Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Let’s start with some brief history on the transition to EV sales, and then get to the big topic: transitioning the ICEV (internal combustion engine vehicle) fleet to electricity.

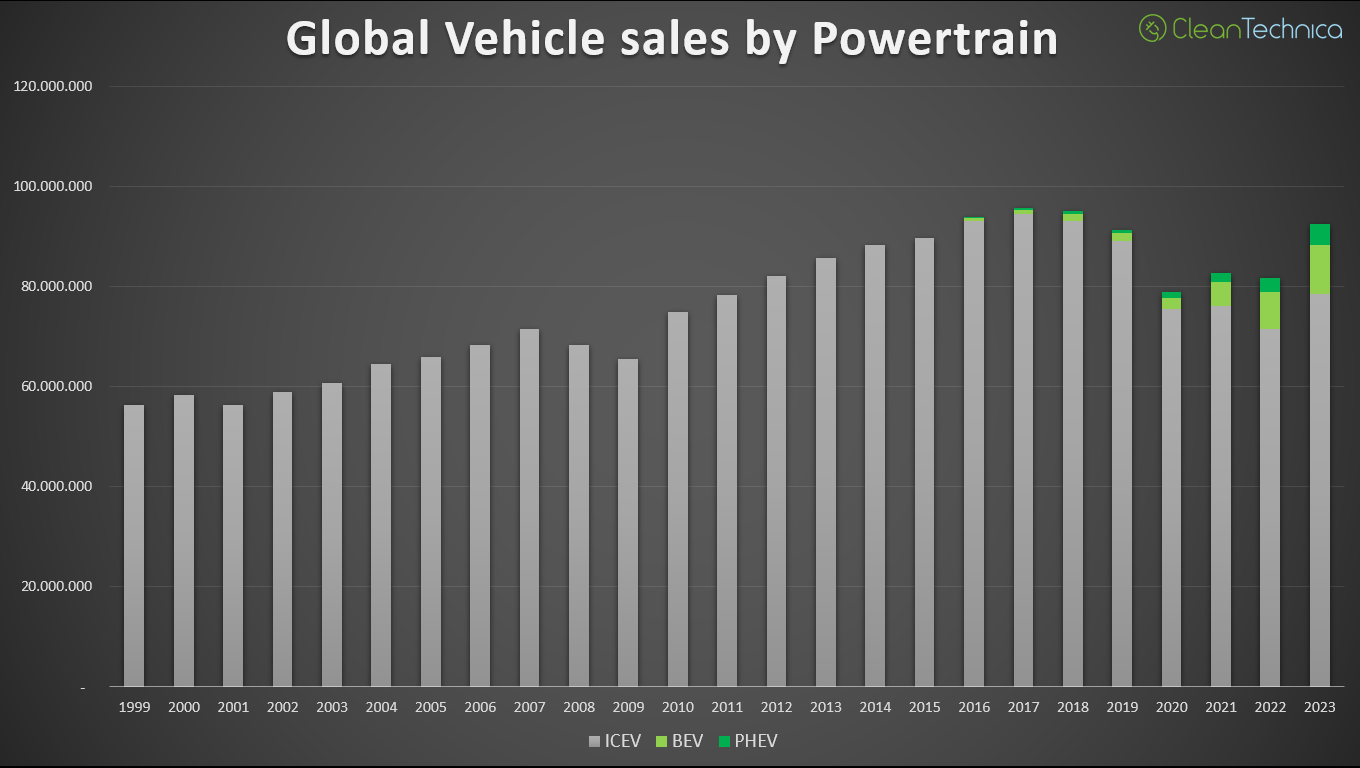

The world passed peak ICEV sales back in 2017

EVs were only a small fraction of total vehicle sales back then and had little part in this phenomenon. It was quite the surprising development when, within a growing world population and a growing world economy, world vehicle sales started to go down.

I won’t delve here into the intricacies of “Peak Car,” and the debate of whether this downturn will be permanent or not. Personally, I think it won’t, but I wouldn’t be confident enough to bet on it. No, what matters here is that because this happened during a technological transition, it meant that if the time ever comes when vehicle sales once again rise, they will most certainly not be ICEVs, but instead BEVs (and, to a lesser degree, PHEVs). Which brings us back to the subheading above. It is a given that by now we’ve surpassed peak ICEV sales.

The path to peak ICEV fleet is a different matter. We may be close to it, but the path may yet be longer than expected. Nobody can see the future, but the current trends provide some insights to make reasonable guesses, and that’s what this article will try to do.

Oh, and I will consider traditional hybrids, mild hybrids, and non-plug-in EREVs as ICEVs. If it doesn’t have a plug, then I’m not counting it as an EV. I will also exclude two- and three-wheelers to keep at least a semblance of simplicity.

Peak ICEV Fleet: The Basics

It is one thing to analyze a local — or even regional — market: to do so, one may look at things like economic development, generational and demographic trends, and urbanism. But to analyze all 190+ of them in one sitting requires a different approach. One must go to the basics.

And, in its most basic form, to calculate the moment when we will reach peak ICEV fleet is quite simple: one must simply add new cars into the fleet, then subtract the ones being scraped. As the latter number may be hard to calculate, one could indirectly calculate the approximate number of scrapped vehicles in any given year by the average time a vehicle lasts.

It stands to reason that the lower the average life of an ICEV, the faster that we will reach peak ICEV Fleet. However, to calculate this average life is hard, as various sources present numbers that go from 11 years in some countries (Belgium) to 23 years in others (Australia, Finland). As new vehicles have increased in price and sales have stalled, average lifespans have also increased in many — probably most — markets around the world. Regardless, the first thing to do is to look to ICEV sales during the last 25 years. Information was not available for every year, so in years prior to 2005, vehicle production was used instead, which should be a close approximation to total sales.

It is important to point out that a large part of the growth seen above had to do with one specific market: China, which went from ~5 million vehicles a year in 2005 to 25 million in 2019 and 30 million in 2023. Other large developing markets such as India (~1.5 million in 2005, ~5 million in 2023) and Indonesia (~500,000 in 2005, ~ 1 million in 2023) have not grown at similar rates nor present similar potential, except perhaps for India.

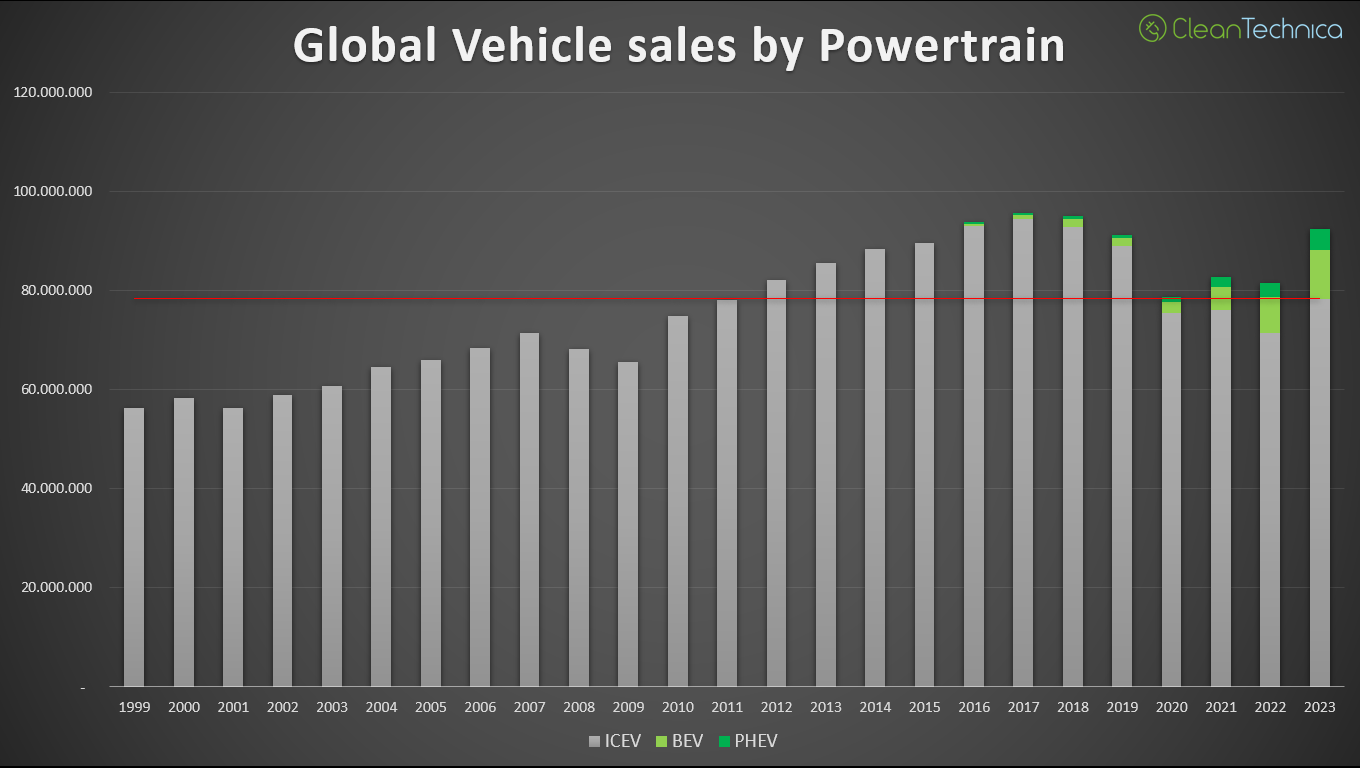

Looking at the data, it’s evident that the post-pandemic recovery in the vehicle market has been almost exclusively led by plug-ins, and that ICEVs have been stagnant since 2020. Furthermore, if we trace a line from 2023’s level, then we can see that it roughly intersects with 2011’s sales number:

This means that the same number of gasoline and diesel vehicles were sold in 2023 as were sold in 2011. In this case, if our average lifespan for a vehicle was 12 years, this would mean that in 2023, no additional ICEVs entered the fleet, because the ones scrapped roughly matched the ones being purchased. Under these conditions, should ICEV sales maintain, the ICEV fleet would reduce continually for the next 8 years, stabilizing somewhere around 2032.

But if you’re here at CleanTechnica, you probably know already that ICEV sales are not going to sustain current levels. Just in 2024, estimates point to an increase of 2–3 million in the total vehicle market, whereas the EV market should increase by 3–6 million. This means that in the best of scenarios for ICEVs, they barely maintain their current sales numbers; most likely, they will lose at least 2 million sales this year.

And it will only get worse, which means we’re very close to peak ICEV fleet.

The Future of the World’s Fleet Depends on How Long ICEVs Last

Our very own José Pontes recently published on LinkedIn that as far as light vehicles go, we’ve already passed peak ICEV fleet. Bloomberg also published that it already happened in 2023 … but that is not including hybrids (also booming in sales) as ICEVs. The Rocky Mountains Institute meanwhile estimates 2025 will be the year.

What these estimates point to is that the average lifespan of vehicles around the world is closer to that of Belgium than to that of Australia. Regardless, we can play a bit with math and create different scenarios to calculate the possible outcomes. At its most basic, two variables define this problem: the number of vehicle sales in the future (EVs and ICEVs), and the average lifespan of ICEVs.

For the average lifespan, we can have two scenarios based upon the averages in different countries:

- ICEVs lasting an average 18 years.

- ICEVs lasting an average 15 years.

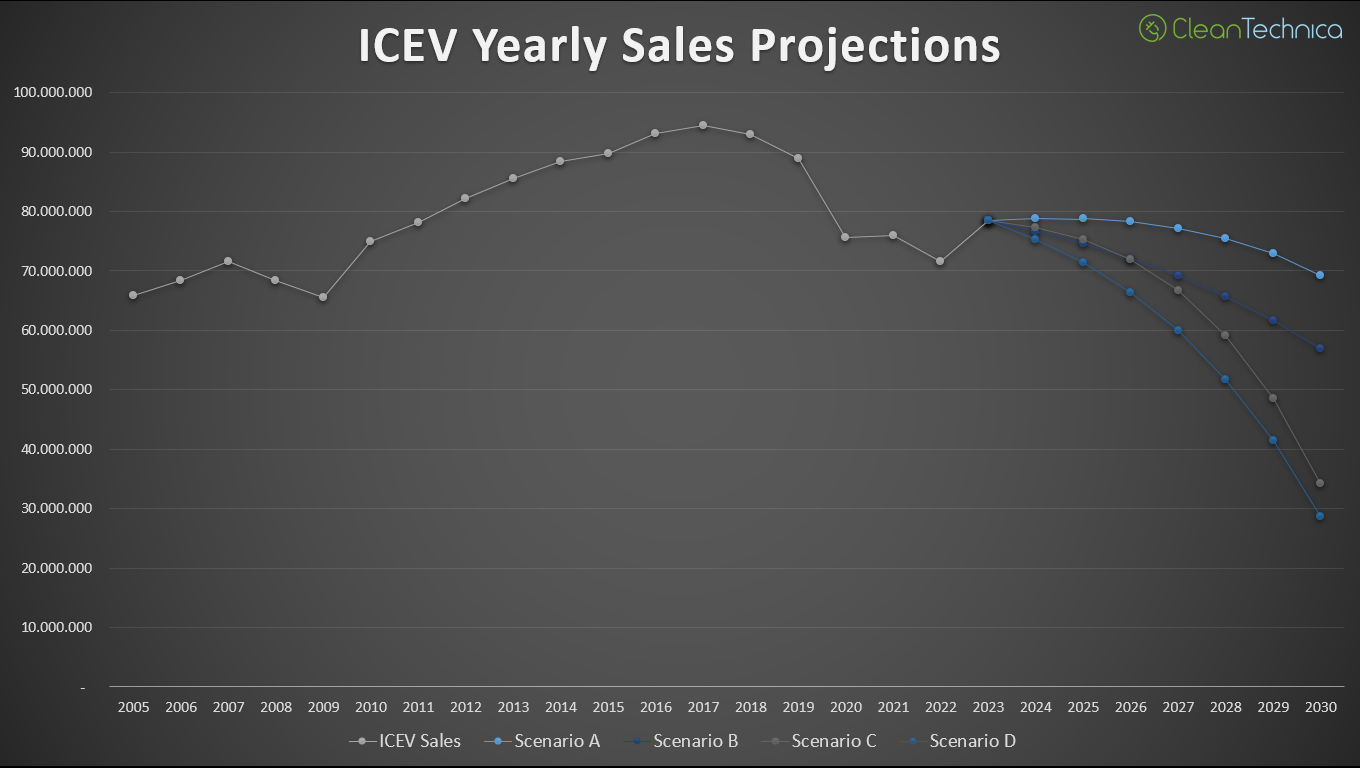

For the number of EVs and ICEVs sold worldwide, we will present four scenarios roughly in line with EV growth rates during the last few years and two different possibilities for total vehicle sales:

- A. Growing vehicle sales (~115 million in 2030) with 40% EV market share by that year. This assumes 3.2% average yearly growth for total vehicles, and 18.5% average yearly growth in EV sales.

- B. Stagnant vehicle sales (~95 million in 2030) with 40% EV market share by that year. This assumes 0.45% average yearly growth for total vehicles, and 15.5% average yearly growth in EV sales.

- C. Growing vehicle sales (~115 million in 2030) with 70% EV market share by that year. This assumes 3.2% average yearly growth for total vehicles and 28.5% average yearly growth in EV sales.

- D. Stagnant vehicle sales (~95 million in 2030) with 70% EV market share by that year. This assumes 0.45% average yearly growth for total vehicles, and 25% average yearly growth in EV sales.

Under these assumptions, ICEV sales during this decade will look as shown below:

All scenarios show ICEV sales falling, but in Scenario A they still amount to 69 million in 2030, whereas in Scenario D they’re below 30 million that year.

Scenario 1: average lifespan of 18 years

This is our “pessimistic” scenario. If ICEVs last longer, this means the fleet (and therefore fuel consumption) will last longer. In this case, we will be comparing our forecasts to sales 18 years earlier to find out the moment that fewer ICEVs were sold than 18 years ago, which would be the moment more of them were scrapped than entered the fleet.

In two of the four scenarios (B, C), this happens in 2028 (which, in this case, means the number of ICEV sales sits below the numbers from 2010). Meanwhile, in our most optimistic scenario D, this is reached as early as 2025 (when ICEV sales fall below the numbers from 2007). As for the most pessimistic scenario A, it takes until 2029.

Now, 18 years average lifespan for a vehicle may seem excessive, so let’s move towards our most optimistic scenario:

Scenario 2: average lifespan of 15 years

This is our “optimistic” scenario because it means that ICEVs will be scrapped sooner. In this case, two of the four scenarios (B, D) get to this point in 2025 (which means fewer cars sold that year than in 2010). Scenario C is not far behind and reaches this point in 2026. Scenario A, once again the most pessimistic of the four, takes until 2027 to get to this point.

Final Thoughts

This analysis isn’t too complex: it departs from the fundamentals and makes some basic assumptions I’d guess most of us agree on. Personally, given the rate of advancement batteries have had, I’d find it very unlikely for EV sales to be below 50% in 2030, but I chose 40% to present a more “pessimistic” perspective. However, if you find that I have a mistake or an invalid assumption, please do comment below to read your point.

What I find here aligns with what other institutions are saying and points to a stagnation of the ICEV fleet worldwide in the immediate term, and a quick reduction starting as early as this year, but more likely in 2025 or 2026. Of course, the ICEV vehicle fleet doesn’t perfectly predict road fuel consumption, but it undoubtedly serves as a proxy for it, so we can conclude that demand for gasoline and diesel is very likely to start going down in the short term.

I don’t believe developing economies will come to the rescue of ICEVs. India is the only big one growing fast enough to remotely compete with the China of the early 2000’s, and even that’s a stretch. Many developing economies have stagnant or even decreasing vehicle markets: Latin America, for example, reached its own peak car sales in the middle of the past decade, as the commodities cycle ended. Colombia’s vehicle market now sits 45% below its peak in 2014, Brazil’s has fallen 38% from its peak in 2012, and even Mexico, with an economy based upon industry and not commodities, presents vehicle sales 15% below their peak in 2016. And this is not including the rapid electrification we’re seeing in several of these markets.

Worse even, many rapidly growing economies in Asia and Africa lack oil reserves and depend on costly imports to sustain their fleets (this includes India). These countries have strong incentives to promote EV use, and, so long as price parity is reached between EVs and ICEVs, they have all the incentives to restrict or outright ban ICEV imports. Some of them are already jumping the gun, as our colleague Remeredzai recently reported.

All in all, these are interesting times we’re living in, and I’m pretty curious as to what 2024 will bring. I did want to make at least a rough calculation on when and how this change will come to be (there’s also the incentive that, if I end up being right, I can pull this article up in a few years for bragging rights). Feel free to comment with your impressions and opinions on these calculations.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Video

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.