Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

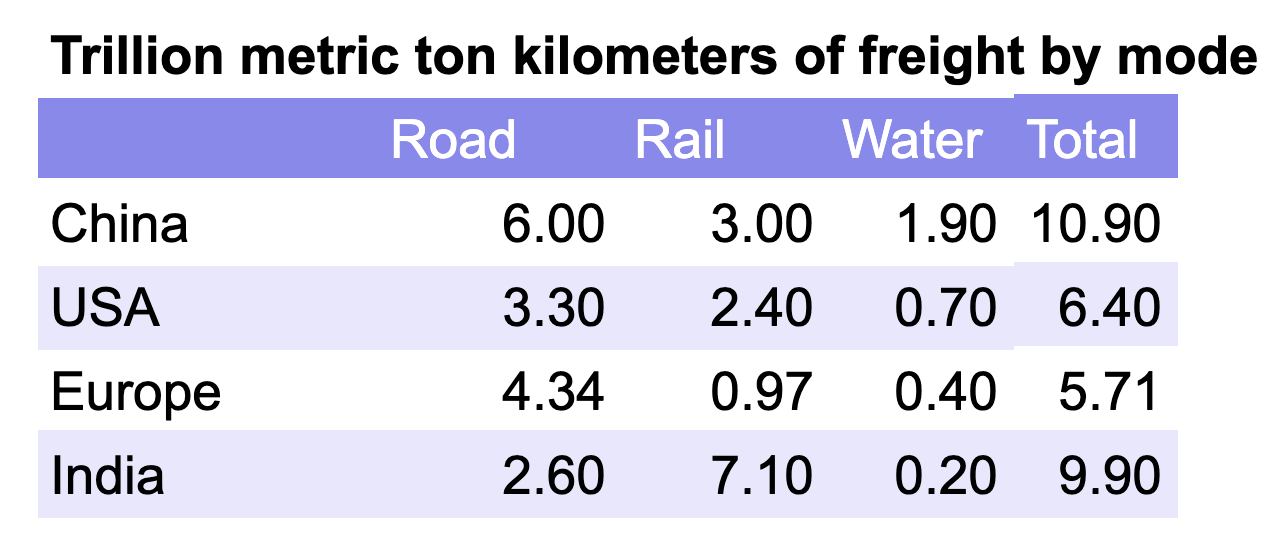

A month ago, I spent some time assembling statistics on major geographies’ split of domestic freight tonnage across different modes: road, rail, and water. I was surprised to find that road freight was so much more dominant in Europe than rail compared to other major geographies. I think of Europe as a rail-centric group of nations, but clearly that’s more aligned with passenger travel than freight movement.

Other aspects to briefly call out are that China has about 600,000 electric trucks running on its roads, so it’s quite a bit further down the road of decarbonizing road freight than the rest of the world. Further, about three-quarters of its rail and all new rail is fully electrified, while North America is at 0% and Europe is barely moving the needle from 60% and could be doing more, but it’s a less significant wedge as well. On the point of water, China’s domestic inland and short sea shipping is still a major transportation mode, and they have already started electrifying it, with several multi-hundred container ships already in service and more being built.

India, on the other hand, while it is trying to shift cargo to its inland waterways, has much less opportunity to leverage that mode than most other continents. India will be at 100% rail electrification this year, so that means domestic freight shipping decarbonization will be a majority solved problem in the country before 2025, something no other geographical region can claim.

While the USA’s transportation blueprint calls for mode-shifting away from road to rail and water, there are different interesting challenges to that. US water tonnage has declined for a long time, even though the Mississippi and coastal shipping are such obvious transportation options. Much of that is due to the Jones Act, the cabotage act introduced after the value of the merchant marine was proven in World War One, which requires all commercial vessels sailing between domestic ports, from ferries to cruise liners to container ships, be manufactured in the USA, owned by US firms, crewed by American citizens and registered in America. Shipbuilding has become an Asia-dominated heavy industry and the Jones Act is preventing American operators from acquiring the best, least expensive modern vessels for every aspect of maritime industry, including offshore wind farm construction and maintenance. Growing domestic American water shipping with the Jones Act in place and a dwindling rump of American shipbuilding is a likely impossible task. Shifting from road to rail has different problems.

This deeply protectionist act has had negative consequences for the USA, and is going to be joined by 100% tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles and other clean technology products which only China manufactures at scale, so the USA is becoming a walled garden full of weeds and thorns as far as climate action goes.

A tremendous percentage of US road freight can simply run with electric semi tractors, and with current battery prices and energy densities, all road freight can be electrified. The central areas, like major port drayage and distribution center to urban deliveries, are easy to provide charging in, and only longer haul trucking is remotely difficult. But while road freight electrification is already under way, the US railroad industry is fighting rail electrification tooth and nail while also facing a third of their cargo going away between coal and oil. Road freight will be electrifying and hence decarbonizing, while rail will still be burning diesel and having plummeting revenues, hence nothing leftover to invest on electrification.

Of course, this has to overcome the US trucking industry’s heavy lobbying to be allowed to burn diesel until the heat death of the universe, as they send representatives to Congress to spread complete and utter disinformation and the creation of new lobbying and disinformation groups. Electrification of US road freight will be hindered by active delaying tactics and once again anti-China tariffs. Unfortunately for Canada and Mexico, they have to live with the results on roads and rail as freight in those modes is effectively a subset of US freight.

Unsurprisingly, given the dominance of road freight in Europe, over 25% of road traffic emissions are from heavy vehicles, which also come with a high-dose of particulates, unburnt hydrocarbon pollution, and other pollutants. In that context, anything that the EU does to reduce emissions from road freight transportation will be a much bigger climate wedge than for other parts of the world. This perhaps explains why so many road freight studies come out of Europe compared to the rest of the world, including the good Swedish study on decarbonization alternatives I participated in recently.

It perhaps also explains all of the bad studies on road freight decarbonization out of the region, where hydrogen often has been purported to be much cheaper than it will be in reality. For several months over late last year and early this year I dug through study after study, usually with European leads or from European institutions dealing with road freight, and most of them had quite bad underlying assumptions around hydrogen. This wouldn’t have been as distressing if they had been from obvious advocacy groups, but they were often from serious, independent and usually rigorous organizations which should have been better, including dena, PIK, and JRC.

Regardless, it makes the recent decision out of the European Council of the European Union very impactful for EU carbon emissions. They will be significantly strengthening requirements for decarbonization across all new heavy vehicles, smaller trucks, urban buses, coaches and tractor trailers.

- 2025: 15% reduction in emissions for heavy lorries over 16 metric tons

- 2030: 45% reduction for all vehicles except urban transit buses, which have a 90% target

- 2035: 65% reduction for all vehicles except urban transit buses, which have a 100% target

- 2040: 90% reduction

Having reviewed and participated in European road transportation studies and looked at vehicle energy infrastructure costs globally, I can say unequivocally that only electric vehicles will fulfill these targets at any reasonable cost. While it is certainly possible to use hydrogen, hydrogen vehicles cost more, hydrogen refueling stations cost more, hydrogen costs more, hydrogen vehicle maintenance costs more, and hydrogen refueling stations costs more, and those costs aren’t going to come down. At present it’s possible to get 8-year warranties on electric buses and 5-year full parts and services contracts with electric buses, while hydrogen vehicles have only reached 20 months.

Regardless, the EU continues to waste a lot of time and money on the transportation dead end of hydrogen, and major OEMs like Daimler Trucking continue to waste time and money on it as well.

Thankfully, funding is available for electric vehicles and charging infrastructure as well, and the vast majority of new zero emissions vehicles are electric. With China’s buses and trucks entering the European market at lower price points for products of equivalent quality, and less anti-Chinese protectionism, Europe is well positioned to electrify its road freight and passenger transportation in these timeframes.

It’s worth pointing out that these are new vehicle sales, not full fleet replacement requirements. Diesel semi trucks, buses, and coaches have average lifespans of about 13 years, so even after 2050 there will still be still be internal combustion buses, coaches, and trucks on Europe’s roads. One of the discussions I had with the Swedish lead of the freight transportation study was related to the pattern of vehicle age and purchases in Europe. The affluent northwest bought new vehicles and the less affluent southeast buys used vehicles off of them. Average vehicle age has been creeping up in recent years, and undoubtedly some operators will choose to game the system by maintaining existing internal combustion vehicles for a few years longer than they otherwise would to avoid the capital cost of buying new electric buses. That’s a problem that will have to be dealt with in the future, but eventually all internal combustion working vehicles will fall apart and there will be no option but electric, even for the diehards.

And so, good news for Europe’s climate targets. Good news for India’s and China’s too, given the freight patterns and current actions. Not so much North America’s, where rail will diminish, water won’t grow, and road freight will remain diesel-heavy for much longer than optimal.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Video

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.