Within the global hierarchy of critical minerals that miners are racing to extract, cobalt remains highly sought after. We explore the cobalt market outlook to 2030.

Generally mined as a by-product of copper or nickel, the transition metal is used for a range of essential applications across defence, aerospace, energy storage, consumer electronics and electric vehicles (EVs).

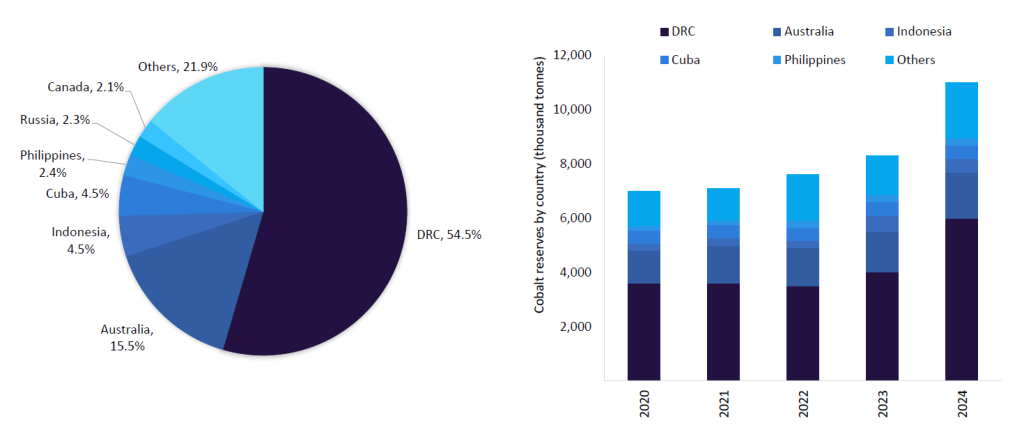

To serve these rapidly growing industries the number of cobalt-producing countries has doubled from seven in 2000 to 16 in 2024, according to Mining Technology’s parent company GlobalData.

While demand remains high, oversupply from major producers, namely the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), has put downward pressure on prices.

In addition, China’s dominance in the global cobalt market has exposed the commodity to escalating tariffs as it has become a tool in geopolitical disputes. The US’ Trade Act currently imposes a 25% tariff on refined cobalt metal imports from China, which is anticipated to intensify with Donald Trump’s second term as president now undeway.

Global cobalt production has achieved year-on-year records, surpassing 200 kilotonnes (kt) in 2023 and 300kt in 2024. Moving forward, international cooperation is essential to effectively balance issues of chronic oversupply and pricing.

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Your download email will arrive shortly

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalData

Cobalt producers, supply and market demand

The DRC is the dominant player in global cobalt production, estimated to account for just over 80% of global output, followed by Indonesia at 6.7%.

While still far behind the DRC, production from Indonesia’s cobalt mines has surged over the past decade, jumping from 1.3kt in 2015 to 20.4kt in 2024. The country has surpassed its competitor Russia to become the second-largest cobalt producer globally.

Despite Russia’s substantial cobalt reserves, the ongoing conflict in Ukraine has triggered severe sanctions and trade restrictions led by the EU and US, hindering Russia’s ability to reliably supply to the global market. Consequently, national cobalt production is projected to stagnate at 3.1% until the end of the decade.

Australia and Canada are also becoming key players as market diversification expands. In 2024 they accounted for only 1.9% of the global share but this is projected to increase to 6% by 2030 due to new projects such as Australia’s Broken Hill Cobalt and Canada’s Copper Cliff mine. Moreover, Australia is primed to capitalise on leading global supplies of environmental, social and governance-compliant cobalt at premium prices.

With production rising internationally, cobalt pricing has been volatile. Following its peak in 2018 at $81,900 per tonne (t), the metal is at a multi-year low due to oversupply and a shift towards lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries that are considered more cost-effective and thermally stable.

Senior mining analyst at GlobalData Vinneth Bajaj highlights that “as alternatives to cobalt batteries mature and become more commercially viable, they could reduce the reliance on cobalt and change the market dynamics”.

Cobalt Institute director general Dinah McLeod tells Mining Technology: “Currently, the cobalt market is enduring a sustained period of market weakness, which is expected to persist as supply outpaces demand, extending market surpluses. Prices will remain under pressure in the short term.

“However, from the mid to late 2020s, strong demand growth is expected to outstrip supply,” she says. “Prices are forecast to recover to incentivise further supply investment and support rising future market demand.”

As the energy transition gains pace, cobalt remains valuable for its use in EVs – an industry that is projected to surpass 60 million unit sales by 2030 globally. Indonesia has capitalised on this interdependence to develop its domestic EV supply chain through cobalt mining, solidifying its position in both markets.

Beyond batteries, cobalt also plays a crucial role in superalloys used in aerospace and military applications. These sectors provide a stable and price-insensitive demand for cobalt, offering steady growth in the medium to long term despite market headwinds.

China’s omnipresence in cobalt

Intertwined throughout the global cobalt supply chain is China, with national state-supported mining companies owning and operating significant assets in key cobalt mining jurisdictions, establishing what Bajaj calls “a near monopoly”.

Since 2008, China and the DRC have operated under an ‘infrastructure for minerals deal’. This was revised at the beginning of 2024 to include a commitment of up to $7bn in infrastructure projects in the DRC in exchange for continued access to its abundant mineral resources.

Chinese mining leader CMOC Group is notable for its control over many of the DRC’s largest cobalt ventures and projects such as the Tenke Fungurume and Kisanfu copper-cobalt mines.

CMOC’s dominance both upstream and downstream has outpaced industry giants such as Glencore, which in August 2024 stopped stockpiling cobalt from its mines in the DRC after its output fell by 27%. Meanwhile, CMOC’s production doubled from 55kt in 2023 to 114kt in 2024.

In Indonesia, Chinese-backed investments have developed advanced high-pressure acid leach (HPAL) facilities to boost local nameplate capacity of cobalt. Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt’s Huafei plant in Indonesia is the largest HPAL facility in the world and 90% of domestic nickel smelters have been built by Chinese companies.

This widespread influence has positioned cobalt between China and the West in “a tale of two markets”, as described by the Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition at the Wilson Center, a non-partisan US research organisation.

Indeed, China’s grip on cobalt has intensified anxieties around dependency in the US, where the focus on critical minerals security and ‘foreign entities of concern’ is set to escalate with the return of Donald Trump as president.

Trump has made clear his intentions to impose tariffs on China, Mexico and Canada, saying post-inauguration that tariffs on Mexico and Canada would arrive in February.

“Tariffs have some short-term benefits, such as encouraging domestic production capacity and potentially accelerating the adoption of alternative technologies like cobalt-free batteries,” Bajaj explains.

“However, potential consequences are increased manufacturing costs and reduced competitiveness, particularly acknowledging China’s substantially established domestic appetite for these materials.”

Trump has yet to turn his attention to other major cobalt producers such as Indonesia, but the current global cobalt trade model remains vulnerable to geopolitical tussles.

Speaking to Mining Technology, Joe Kaderavek, CEO of Australia-based Cobalt Blue, explains the position of producers flanked by China and the US. “Trump has a far more substantial lever through tariffs than the Democrats ever had through tax credits for EVs and batteries. They will come in heavily and avoiding that burden is worth a lot to Western cobalt.” Cobalt Blue is developing the Broken Hill cobalt project, an integrated mine-refinery concept in far western New South Wales, although the mine plans are currently under review due to market conditions.

In the global picture, McLeod asserts: “If cobalt’s potential is going to be fully unlocked to support the energy transition, governments will have to implement effective policies to incentivise demand and competitively grow supply.”

Where is cobalt mining headed?

Global cobalt production is forecasted by GlobalData to reach 410.9kt, increasing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.1% by 2030.

In the DRC, production rates are expected to moderate with an output of 271.3kt and a CAGR of 1.8%. While this signals a long-term easing of oversupply, the industry continues to expand. Twenty-five cobalt projects are in various stages of development with high likelihoods of coming online by 2030, including Vale’s Pomalaa mine in Indonesia and Shalina Resources’ Mutoshi mine in the DRC.

Much of cobalt’s market trajectory depends on its origin as a secondary element extracted from copper and nickel ores. As highlighted by the Wilson Center, copper-cobalt miners have not come under as much pressure as nickel-cobalt miners due to comparatively more robust copper prices.

Financing remains a major barrier, says Kaderavek. “The cobalt price signal creates an incentive for development, but this is at least two or three years away. So cobalt’s outlook is one of very stunted growth for the Western world, because even once we get incentive pricing, lenders need confidence that that pricing will remain.”

Demand could shift further with the growing prevalence of LFP batteries. “While the transition to cobalt-free batteries is expected to be gradual, it poses a potential threat to cobalt demand in the long term,” says Bajaj.

The cobalt supply chain is also shifting due to regulatory changes. From May 2025, the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) will require upstream and downstream companies to conduct risk assessments and take action if ESG issues are identified to avoid being blocked from public and private financing in the bloc.

ESG concerns have cast a dark cloud over cobalt mining, including environmental pollution, hazards to worker safety and alleged labour abuse. If left unchecked, this brings into question cobalt’s place in responsible mining as ESG progress becomes increasingly critical to the industry’s future.

The Cobalt Institute previously warned that regulations such as the CRMA are “the beginning of a new trend of hard law legislation. Cobalt companies should prepare for that inevitability.”

“Investment, new mines and good policies are urgently needed to build a robust cobalt value chain that is ready to help achieve a successful global transition to net-zero,” concludes McLeod.