Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Plugin hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) divide opinion all the time, as they have for years. A lot of people feel that with the way BEV tech has advanced in recent times, PHEVs are no longer needed as a transition option to full electric. However, as Dr. Maximilian Holland says, “BEVs pollute less than PHEVs, but the latter still have a critical role in certain niches where BEVs may not yet fully meet users’ needs. PHEVs (or EREVs) — when plugged in as designed — pollute a lot less than HEVs, which in turn pollute less than diesels!”

PHEVs with electric ranges of 200–300 km would appeal to non-early adopters, especially in markets where charging infrastructure is not fully developed. Perhaps this is what some Chinese automakers are thinking, as quite a number of them are contributing to a new wave of new-generation PHEVs with battery packs of over 50kWh and electric ranges of about 200 km, thereafter complemented by a 1.5T or 2.0T ICE engine.

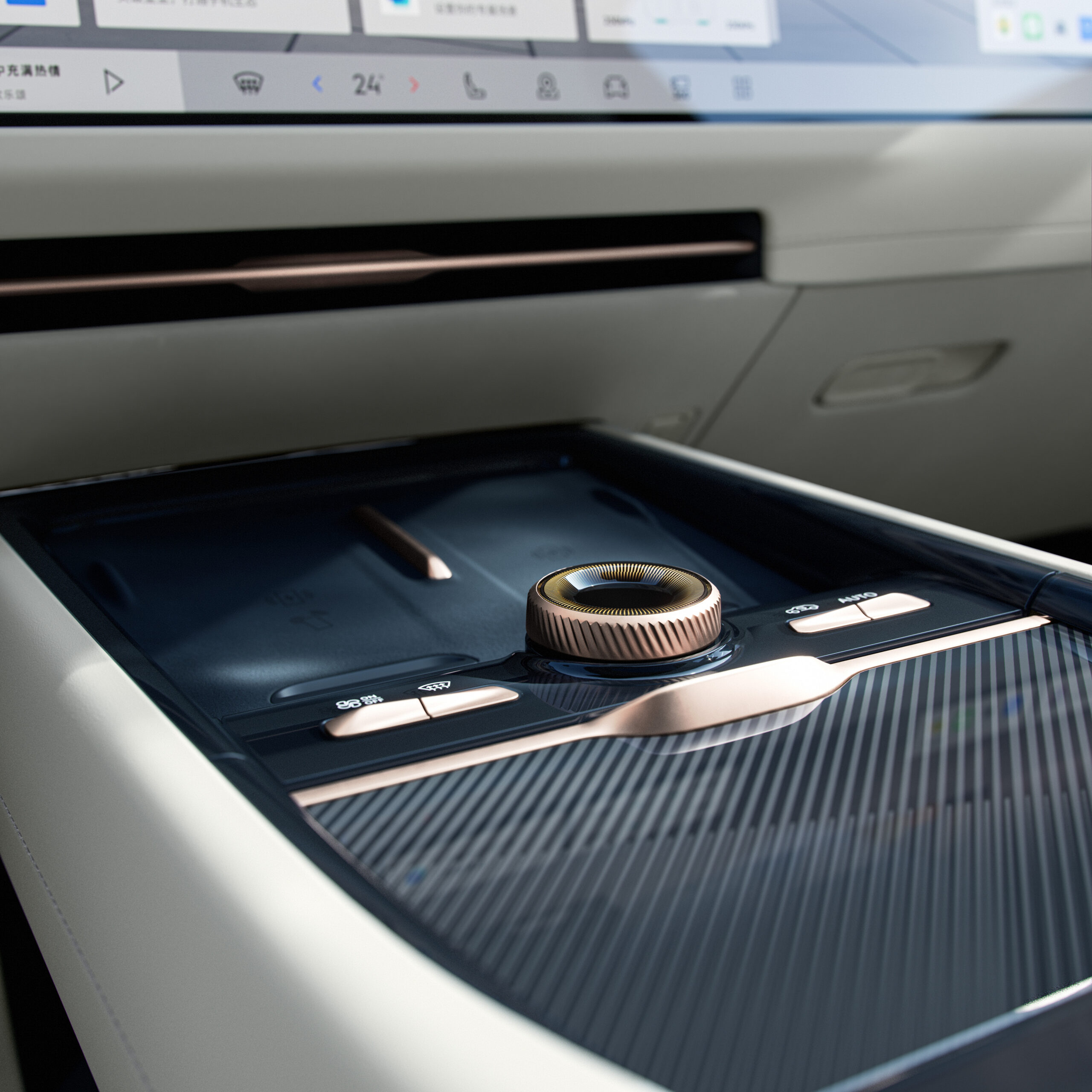

Lets us look at a couple of interesting PHEVs that have been recently showcased in China. The Lynk & Co 900 is one of the “long range in electric mode” PHEVs attracting a lot of attention. Positioned as a new six-seat flagship SUV for the brand, it is a large SUV with a wheelbase of 3160mm and dimensions of 5240/1999/1810mm. The top-spec model gets four motors! A 2.0 turbo (187 kW) plus three electric motors (123 kW at the front plus 2 x 160 kW at the back). This gives a total of 630 kW. The rest of the models get either a 1.5T or a 2.0T ICE engine with 2 electric motors (123 kW at the front plus 230 kW at the back) for a total of up to 540 kW. Top speed is stated to be limited to 200 km/h. Inside, you get a 30-inch ultra-wide 6K screen. How cool is that? The Lynk &Co 900 gets a big battery compared to normal PHEV batteries most people around the world would be used to. It gets a 50 kWh battery enabling a range of about 200 km in electric mode, gauging from similar vehicles.

Another interesting one is the new GWM Tank 500 on the Hi4-Z platform. Great Wall Motors says the new Tank 500 has its battery located between the front and the rear set of wheels in the chassis. The Tank 500 PHEV has a 59.05 kWh battery pack providing a range of 201 km in electric mode (WLTC). The combined range is over 700 km. Energy density of the battery pack is listed as 234Wh/kg. The Tank 500 PHEV has a 2.0 turbo (185 kW/380 Nm of torque) ICE engine plus two electric motors (215 kW/400 Nm of torque at the front and 240 kW/415 Nm of torque at the back). Altogether, the Tank 500 PHEV has a peak power of 635 kW. It also gets 163 kW maximum charging power.

All of this got me thinking. Some of these models, such as the Lynk & Co 900, could be positioned for the international market as well and could be part of some sort of “soft landing” for plug-in vehicles, especially in countries where the electric mobility market is still small or non-existent. These kinds of vehicles could be particularly useful in developing countries where charging infrastructure is not yet widely developed. In quite a number of countries in Africa, for example, government and corporate fleets make up most of the brand new vehicle purchases. These purchases tend to lean toward large SUVs such as Toyota Land Cruisers. Plug-in hybrid SUVs with ranges of around 200 km in electric mode while also giving users some insurance from the contribution of the ICE engine could meet basically all their driving needs within urban centres as well as on longer journeys to remote areas where charging infrastructure may still not be available. This “safety net” whilst still reducing overall fuel consumption compared with similar ICE vehicles may well be the stepping stone needed to entice these fleet operators to start their electrification journey.

With these vehicles said to have full off-roading capability similar to popular ICE models used by governments, NGOs, corporate fleets, they could just be the vehicles to entice these key stakeholders to start their journeys to electrification. Most people’s urban daily round trip commutes are around 30–40 km. In city driving cycles, it’s quite possible to get about without bothering the 2-litre ICE incorporated into these PHEVs given their 200 km range in electric mode. These fleet operators could then be incentivized to install charging stations at their offices and facilities to support charging of these vehicles without the need to wait for a larger public charging network elsewhere. The impressive range is also perfect for some of the popular commutes to satellite towns, such as the 70 km Harare–Marondera (Zimbabwe), the 66 km Pretoria–Johannesburg (South Africa), the 90 km Nairobi–Naivasha, and the 45 km Nairobi–Thika (Kenya).

Commuters can enjoy the electric drive with minimal assistance from the partner internal combustion engine for most of the journey depending on their speed and driving style. For an all day stay, commuters can even top up the battery again whilst the vehicles are parked and head back later enjoying the electric drive. This will certainly get drivers to familiarize themselves and get comfortable with plug-in EVs without the fear of being stranded on the highway knowing they have a tank of something they are more familiar with as backup. As they get more comfortable with their PHEV, they will drive in electric mode most of the time, leaving the ICE platform for the occasional road trips that are longer than 150 km. As users of electrified vehicles, it may incentivize them to formulate pro-EV policies across the continent to the benefit of their constituents. They will also be jolted into action to install charging stations at government facilities, offices as well as other public places, building a charging network that can be opened to the public visiting these facilities. This could encourage other workers at those facilities as well as other users to also buy electric vehicles.

Most of these cars are replaced after 3 or so years, or after a certain mileage, whichever comes first. Some of these vehicles then find themselves on the used vehicle market when they receive their upgrades, which can be a positive in this case, as the inventory of electrified vehicles on the market will grow. The vehicles will now be available at price points more palatable for another tier of potential buyers. As they get used to living with these “longer range PHEVs,” they will probably get comfortable with the idea of switching to fully electric vehicles. As battery technology keeps getting better and the price of batteries keep falling, fully electric vehicles with ranges of over 700 km in this particular vehicle segment, as well as others, will become more common, charging infrastructure will have also grown by then, and more people will therefore get more comfortable going fully electric in these places.

PHEVs had a record year in China in 2024. Will PHEVs get back into fashion as “transition vehicles to full electric” in more places around the world? Let us know what you think in the comments section.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy