Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

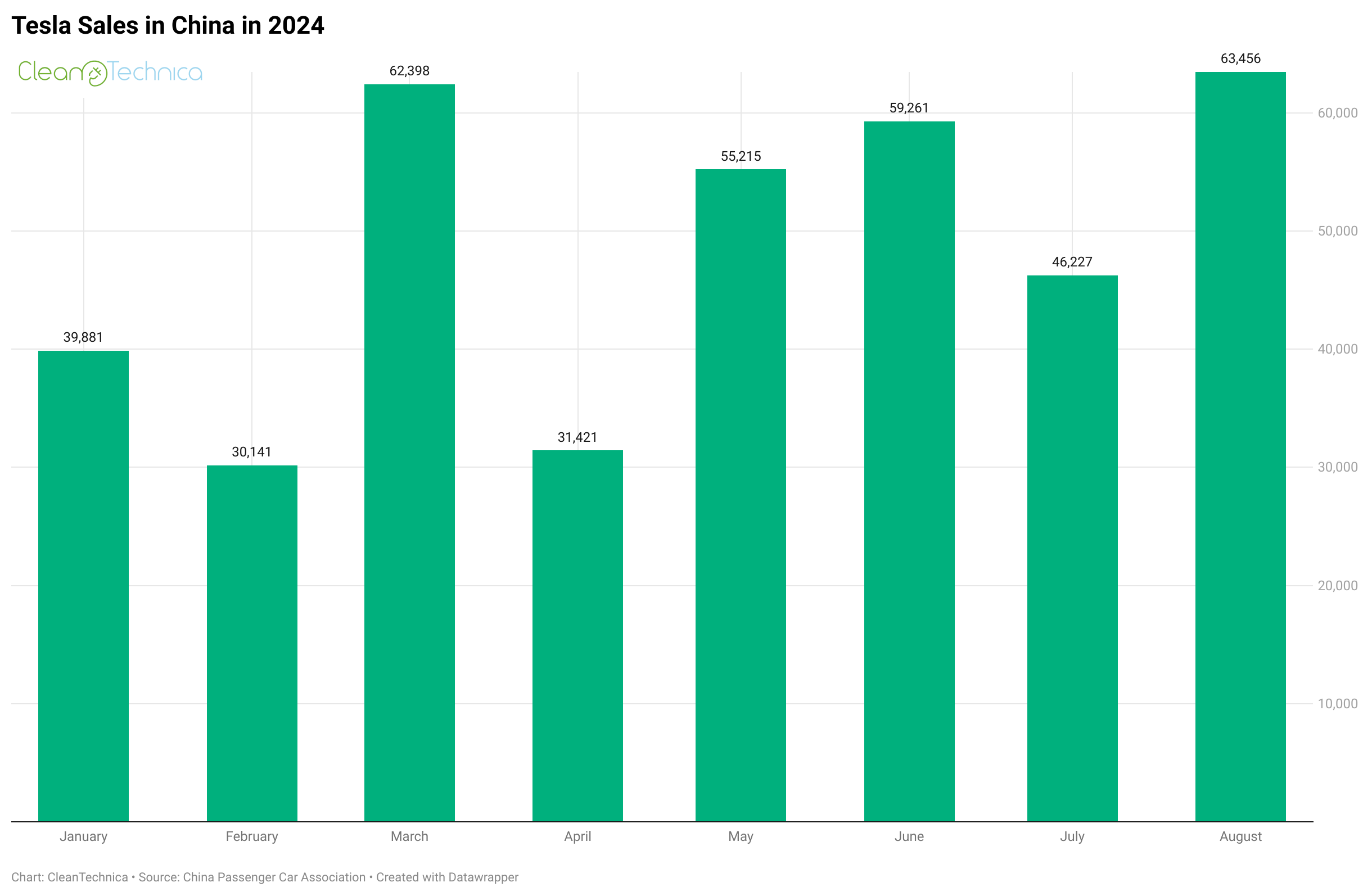

On October 27th of 2020, the China Society of Automotive Engineers laid out a roadmap for how the country was going to achieve 50% of all cars sold in 2035 being fully electric, plug-in hybrid, or hydrogen, with 95% of them of course being fully electric. Per projections from HSBC, UBS, Morningstar, and Wood Mackenzie, that’s actually going to happen in 2025, a full decade early, with of course hydrogen cars at perhaps 0.02%, approaching zero.

Meanwhile, the nuclear capacity target for 2020 was 58 GW and the country is currently sitting at 56.9 GW per the World Nuclear Association. One of these things is not like the other, one of these things is not the same.

As I gear up for my now annual comparison of the pace of renewables in China vs. the pace of nuclear, something I’ve been publishing on since 2014 and which was included in the best-selling business book How Big Things Get Done by authors Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Garder in 2023 because it was so resonant with their “What’s Your Lego?” chapter, news of the EV target being crushed caused me to do a check on its nuclear progress.

This is par for the course for China’s real decarbonization efforts, as the country surpassed its 2020 renewable energy targets while not meeting its nuclear targets. The nation’s wind energy capacity reached 281 GW, far exceeding the target of 210 GW. Solar power saw even more dramatic growth, with installed capacity soaring to 253 GW, well above the 105 GW goal. Hydropower, a long-standing pillar of China’s renewable energy strategy, also surpassed expectations, achieving approximately 370 GW compared to the target of 350 GW.

China’s 2025 targets include generating 33% of its electricity from renewables, ensuring renewables accounted for over half of its total installed power capacity, and achieving 3.3 trillion kWh of annual power generation from renewable sources. China is ahead of schedule here as well, with renewable energy installations already surpassing the 2025 target, comprising 53.8% of the nation’s total installed capacity as of mid-2024. Renewable electricity generation is also on track to meet the 33% target.

As of November 2024, China has had wind power installations totaling 490 GW, marking a 19.2% increase year on year. Solar capacity surged to 820 GW, reflecting a 46.7% rise over the previous year. And hydropower remains a significant component of the energy mix at 426 GW.

Meanwhile, China’s 2025 target of 70 GW of nuclear capacity is clearly not going to be achieved. As I wrote earlier this year, in “China Still Hasn’t Learned Nuclear Scaling Lesson With New Approvals,” the plan, which I don’t believe is credible, aims to add 5.1 GW of capacity in 2025, so the nuclear program will only be five years behind, not further. But that only brings the total over 60 GW, not to 70 GW.

As I engage with people globally, China’s nuclear program frequently comes up, as it did in Michael Liebreich’s redux conversation with Amory Lovin, just republished in his Cleaning Up podcast and worth listening to. People keep pointing to it as the reason why nuclear is the answer to climate change, yet the reality is that even China can’t build it to targets or schedule.

This is the country which has built around 500 cities, 177,000 kilometers of highways, 46,000 kilometers of high-speed electrified passenger and freight rail, 426 GW of hydroelectric capacity, 65 GW of pumped hydro, and dozens of the biggest ports in the world, all since 1980. This is a country which knows how big things get done, and even it can’t get nuclear done.

This is a country which has consistently been underpromising and overdelivering in area after area. This is a country which now has more materials scientists, power engineers, nuclear engineers, and civil engineers than the rest of the world combined, which has strong governmental and industry support for BIM and structural analysis and design software adoption and use, which has built more nuclear reactors in the last 25 years than the rest of the world combined, and it still can’t get its nuclear program to deliver against targets.

China didn’t adjust its 2025 nuclear target downward after falling far short of its 2020 targets. It’s not like the industry and program haven’t known what the 2025 target was for more than a decade. It’s not like the nuclear industry was uniquely hit by COVID-19. It’s not like the nuclear program hasn’t been a national strategic priority supported at the highest levels for decades. The nuclear program and industry simply can’t deliver, even in China with far more of the conditions of success than any other country in the world.

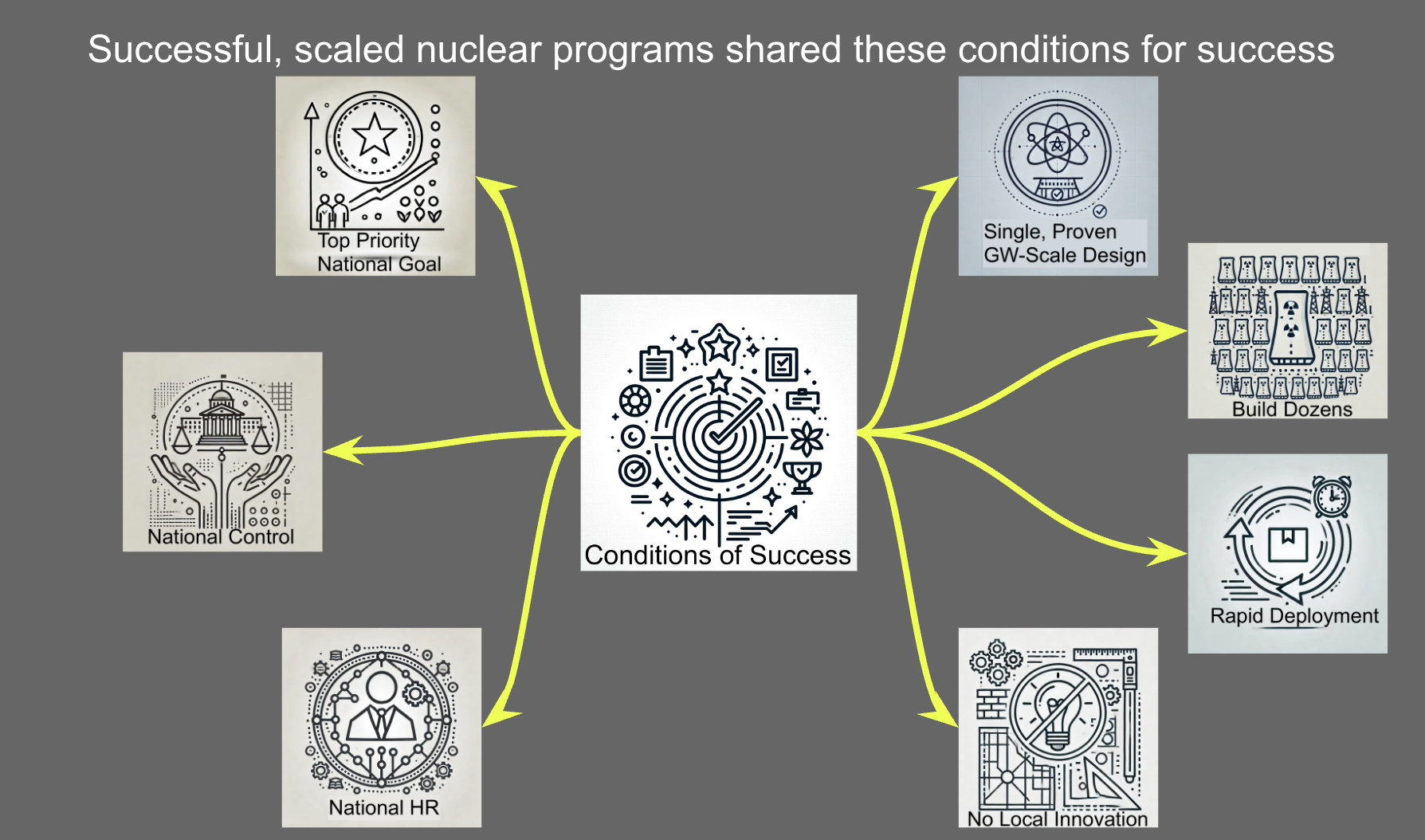

As a reminder, the conditions for success are pretty well known from observation of what’s worked in the past. Where nuclear programs have achieved reasonable success, like the USA, France and the UK in the second half of the 20th century, they were national strategic programs aligned with a need for nuclear weapons, under national control — not provincial, state and or utility — with a national human resources program to build the nuclear engineering competency and maintain it for decades. They deployed one or two usually closely related designs of big reactors, GW scale. They built dozens of them to enable the lessons learned from each to inform the others. They did it quickly, in 20 to 30 years, not spread over sixty years, to enable the human resources with experience to be leveraged before retirement, something that’s going to be impacting China’s nuclear program now of course.

And no local innovation is permitted. Improving stuff, which engineers love to do, is the kiss of death for nuclear economics. This keeps being proven, and the west keeps forgetting it. China too, as it’s building a lot of designs of a lot of nuclear technologies because its export strategy has trumped its electrical generation strategy. That’s the one condition of success it failed to create.

Even China couldn’t create all the conditions for success, and that’s proven by them consistently failing to meet remarkably small targets. Remember, the target for EVs was 50% of all sales, while the target for nuclear was about 2% of electrical generation capacity. The target for renewables was 50% of all capacity, while the target for nuclear was 2% of capacity.

China is currently at 3,230 GW of generating capacity. Its current nuclear capacity is about 1.76%.

And yes, for the nuclear die hards in the crowd, nuclear’s capacity factor is higher, especially China’s as the plants are much newer than the world average. But it really doesn’t matter when the total capacity is 1.76% of total capacity, it’s building nuclear so slowly and it’s adding 300 GW of renewables capacity every year. At the end of 2025, nuclear is going to have an even lower percentage of capacity and likely a lower percentage of electrical generation as well as China’s electrical demand continues to soar, following a trajectory much steeper than the west’s.

China’s nuclear energy is a rounding error. While China is smashing other targets, in the case of EVs by a decade and in the case of renewables by years, it still hasn’t met 2020 targets for nuclear.

China’s target for nuclear for 2030 is 120 to 150 GW. However, China’s current reactors in construction and in plan through 2030 only bring the total up to about 88 GW. They aren’t capable of scaling nuclear construction to anywhere near what the target was, and as I noted, I don’t believe the nuclear construction plan for the next five years is remotely credible.

The people and organizations promoting nuclear as even a tiny part of the solution to climate change really need to accept the reality that if China can’t get it right, the odds of any other country or bloc getting it right in the 21st Century approaches zero. Certainly the small modular nuclear reactor crowd have shown that they didn’t even understand the conditions for success, as they are intentionally violating virtually all of them.

This is why I say that a lot of conservative politicians love promising nuclear energy as a solution to climate change. It means that they don’t have to do anything in reality, they please the nuclear fanbois in their constituencies and they appear to be taking climate change seriously. What it really means is delaying real climate action, which many of them think is exactly the right thing to do as their fossil fuel donors and lobbyists are making sure it’s in their personal best interest to keep burning the stuff.

China’s emissions are going to plummet in coming years, in part because they are reaching the end of their massive infrastructure build out and will be turning off the coal-powered cement and steel plants that provided the necessary construction material for it, in part because they have built and are building more renewables at an extraordinary pace, and in part because they have aggressively electrified every segment of their economy which will persist. It’s a simple recipe for an economy, and yet the west is making cupcakes instead.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy