Did you know the Fed has already loosened monetary policy?

While everybody focuses on the prospect of a Federal Reserve interest rate cut and salivates in the hope of easier money, most people completely ignore the other prong of central bank monetary policy – the Fed balance sheet.

As former Federal Reserve Governor Kevin Warsh put it in an op-ed published by the Wall Street Journal, interest rates are a sideshow in the Fed drama.

But out there in the mainstream, interest rates are the only show in town. The balance sheet is the sideshow. But while it might be considered a sideshow, it’s one worth paying attention to.

In May, the Fed quietly announced that it would begin to taper balance sheet reduction.

The balance sheet serves as a direct pipeline to the money supply. When the Fed buys assets – primarily U.S. Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities – it does so with money created out of thin air. Those assets go on the balance sheet and the new money gets injected into the economy.

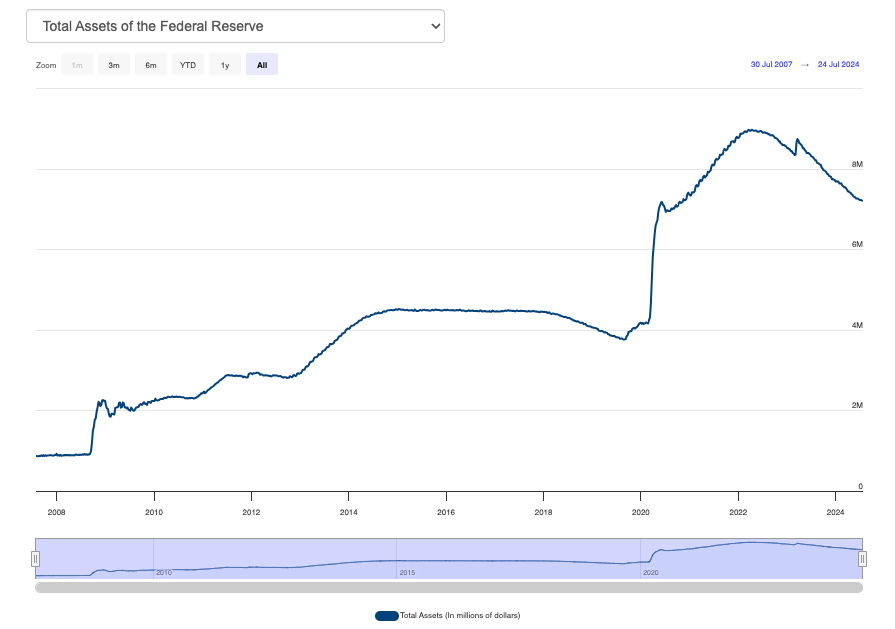

Before the 2008 financial crisis and Great Recession, the balance sheet was just over $900 billion. By the end of the pandemic era, it stood at just under $9 trillion.

In other words, the Fed pumped over $8 trillion into the economy in 14 years.

During the pandemic alone, the Fed expanded that balance sheet by nearly $5 trillion.

Warsh outlined the effects of this unprecedented monetary expansion.

“The monetary base is up 60 percent since the pandemic. Another measure of money, M2, is up 36 percent in the past four years. The inflation surge in the same period– cumulatively about 22 percent– shouldn’t have been a surprise.”

It shouldn’t have been a surprise because this massive increase in the money supply is, by definition, inflation. This monetary inflation is the root of the price inflation we’re still suffering from today.

If expanding the money supply is inflationary, it logically follows that to truly beat down price inflation, the Fed needs to shrink the balance sheet. Rate hikes aren’t enough to ring all the liquidity out of the economy. Warsh made this very point in his op-ed, explaining that if the Fed is serious about taming inflation, it needs to significantly reduce the size of the balance sheet. In other words, it needs to undo the money creation of the past decade-plus.

I didn’t.

And it won’t.

The Fed did make a half-hearted effort to shrink the balance sheet. Since the pandemic peak, the central bank has run off about $1.76 trillion. That sounds like a lot until you remember that it added almost $5 trillion in just two years.

And now the central bankers at the Fed have already started tapering the balance sheet.

The plan wasn’t exactly ambitious to begin with.

The Fed announced a balance sheet reduction plan in March 2022 when it could no longer convince everybody that price inflation was “transitory.” It called for $30 billion in US Treasuries and $17.5 billion in mortgage-backed securities to roll off the balance sheet in June, July, and August of 2022. That totaled $45 billion per month. The Fed said it would increase the pace to $95 billion per month in September 2022, capping the U.S. Treasury roll-off at $60 billion.

If the Fed followed the blueprint, it would take 7.8 years for the Fed to shrink its balance sheet back to pre-pandemic levels.

That doesn’t even begin to account for the inflation it created after the 2008 financial crisis.

So, if inflation isn’t at the 2 percent target why did the Fed start winding down balance sheet reduction in June?

Probably because they learned their lesson in 2018.

When then-Fed chair Ben Bernanke launched the first round of quantitative easing (QE) at the onset of the Great Recession, he assured Congress that the Fed was not monetizing debt. He said the difference between debt monetization and the Fed’s policy was that the central bank was not providing a permanent source of financing. He said the Treasuries would only remain on the Fed’s balance sheet temporarily. He assured Congress that once the crisis was over, the Federal Reserve would sell the bonds it bought during the emergency.

That didn’t even begin to happen until late 2017. And it abruptly stopped in the summer of 2019 having made very little progress in keeping Bernanke’s promise.

Why?

Because the monetary tightening was about to break the economy and the financial system.

The stock market crashed in the fall of 2018 and there were recession warning signs flashing in the economy. The Fed put rate hikes on hold in December that year and started cutting rates in 2019. In August 2019, the Fed reversed course on balance sheet reduction and launched a new round of quantitative easing as the short-term lending markets went haywire. Fed officials refused to call it QE. They even denied that it was QE. But whatever you want to call it, the result was the same as QE. The balance sheet began to expand again.

The Fed was able to shrink the balance sheet more this time around because the monetary expansion was bigger and faster during the pandemic than it was in 2008. But the central bankers know they’re playing with fire. They know that this economy can’t run without easy money. And that’s exactly why they’ve already slowed their roll even though they continue to claim inflation isn’t dead yet.

Keep this in mind as you digest all the talk-talk-talk surrounding the July FOMC meeting. The mainstream talking heads and the markets will focus on “will they or won’t they” cut rates. But the Fed has already loosened monetary policy. And it wasn’t all that tight to begin with.

And I wouldn’t be surprised if we see quantitative easing back on the scene in the near future. The national debt just eclipsed $35 trillion. Uncle Sam is going to need the Fed to get back into the Treasury buying business to support all of the borrowing.

So, what’s the bottom line?

The Federal Reserve has already waved the white flag. It has surrendered to inflation.

That means you’re getting more inflation.

Be prepared.

*********